LAN 102: Network Hardware And Assembly

Switches For Ethernet Networks

As you have seen, modern Ethernet workgroup networks—whether wireless or wired with UTP cable—are usually arranged in a star topology. The center of the star uses a multiport connecting device that can be either a hub or a switch. Although both hubs and switches can connect the network—and can have several features in common—only switches are normally used today. The differences between them are significant and are covered in the following sections.

All Ethernet switches have the following features:

- Multiple 8P8C (RJ-45) UTP connectors

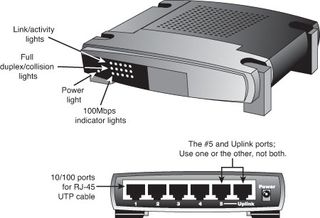

- Diagnostic and activity lights

- A power supply

Ethernet switches are made in two forms: managed and unmanaged. Managed switches can be directly configured, enabled or disabled, or monitored by a network operator. They are commonly used on corporate networks. Workgroup and home-office networks use less expensive unmanaged switches, which simply connect computers on the network using the systems connected to it to provide a management interface for its configurable features.

Signal lights on the front of the switch indicate which connections are in use by computers; some also indicate whether a full-duplex connection is in use. In addition, multispeed switches may indicate which connection speed is in use on each port. A switch must have at least one 8P8C (RJ45) UTP connector for each computer you want to connect to it.

How Switches Work

UTP Ethernet networks were originally wired using hubs. When a specific computer sends a packet of data to another specific computer through a hub, the hub doesn’t know which port the destination computer is connected to, so it broadcasts the packet to all of the ports and computers connected to it, creating a large amount of unnecessary traffic because ports and systems receive network data even if it is not intended for them.

Switches, as shown in the figure below, are similar to hubs in both form factor and function, but they are very different in actual operation. As with hubs, they connect computers on an Ethernet network to each other. However, instead of broadcasting data to all of the ports and computers on the network as hubs do, switches use a feature called address storing, which checks the destination for each data packet and sends it directly to the port/computer for which it’s intended. Thus, a switch can be compared to a telephone exchange, making direct connections between the originator of a call and the receiver.

Stay on the Cutting Edge

Join the experts who read Tom's Hardware for the inside track on enthusiast PC tech news — and have for over 25 years. We'll send breaking news and in-depth reviews of CPUs, GPUs, AI, maker hardware and more straight to your inbox.

Because switches establish a direct connection between the originating and receiving PC, they also provide the full bandwidth of the network to each port. Hubs, by contrast, must subdivide the network’s bandwidth by the number of active connections on the network, meaning that bandwidth rises and falls depending on network activity.

For example, assume you have a four-station network workgroup using 10/100 NICs and a Fast Ethernet hub. The total bandwidth of the network is 100 Mb/s. However, if two stations are active, the effective bandwidth available to each station drops to 50 Mb/s (100 Mb/s divided by 2). If all four stations are active, the effective bandwidth drops to just 25 Mb/s (100 Mb/s divided by 4)! Add more active users, and the effective bandwidth continues to drop.

If you replace the hub with a switch, the effective bandwidth for each station remains at the full 100 Mb/s because the switch doesn’t broadcast data to all stations.

Most switches also support full-duplex (simultaneous transmit and receive), enabling the actual bandwidth to be double the nominal 100 Mb/s rating, or 200 Mb/s. The following table summarizes the differences between the two devices.

| Ethernet Hub and Switch Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Hub | Switch |

| Bandwidth | Divided by total number of ports in use | Dedicated to each port in use |

| Data transmission | Broadcast to all connected computers | Broadcast only to the receiving computer |

| Duplex support | Half-duplex | Full-duplex when used with full-duplex NICs |

As you can see, using a switch instead of a hub greatly increases the effective speed of a network, even if all other components remain the same. Originally switches were very expensive, so many networks were built using hubs instead. But once the price of a switch fell to equal or below the cost of a hub, hubs became obsolete.

Note: Both wired and wireless routers (a router connects a local area network to a device that provides Internet access, such as a cable or DSL modem) typically incorporate full-duplex 10/100 (Fast Ethernet) or 10/100/1000 (gigabit Ethernet) switches.

For more information about routers, see Scott Mueller's Upgrading And Repairing PCs, 20th Edition, “Routers for Internet Sharing,” p. 787 (Chapter 16, “Internet Connectivity”).

At this point the lower cost and significantly higher performance of switches mean that you should consider replacing any hubs that might still be in use.

Additional Switch Features You Might Need

Most switches have the following standard or optional features:

- Multispeed capability—Switches support multiple speeds. This means you can mix gigabit Ethernet (1000BASE-TX), Fast Ethernet (100BASE-TX) and 10BASE-T clients on the same network, and each will run at the maximum possible speed. These days I recommend buying only gigabit switches, since most network adapters now support gigabit speeds.

- “Extra” ports beyond your current requirements—If you are connecting four computers into a small network, you may only need a four-port switch, which is the smallest generally available. But if you buy a switch with only four ports and want to add another client PC to the network, you must add a second switch or replace the switch with a larger one with more ports.

Instead, plan for the future by buying a switch that can handle your projected network growth over the next year. If you plan to connect more than four workstations, buy at least an eight-port switch. (The cost per connection drops as you buy hubs and switches with more connections.) Even though you can easily interconnect additional switches, it is normally more economical to use as few switches as possible.

Note: The uplink port on your switch (or hub) connects the device to a router or gateway device that provides an Internet connection for your network. When multiple switches are to be used, they are usually connected directly to the router or gateway instead of chained (or stacked) off each other.

Modern switches feature Auto-MDIX (automatic medium-dependent interface crossover) ports that allow switches to be connected together using any of the ports, and without using special crossover cables. Older switches (or hubs) used uplink ports to allow additional switches to be connected.

Switch Placement

Although large networks have a wiring closet near the server, the workgroup-size LANs found in a small office/home office (SOHO) network obviously don’t require anything of the sort. However, the location of the switch is important, even if your LAN is currently based solely on a wireless Ethernet architecture.

Ethernet switches (and hubs) require electrical power, whether they are small units that use a power “brick” or larger units that have an internal power supply and a standard three-prong AC cord.

In addition to electrical power, consider placing the hub or switch where its signal lights will be easy to view for diagnostic purposes and where its 8P8C (RJ45) connectors can be reached easily. This is important both when it’s time to add another user or two and when you need to perform initial setup of the switch (requiring a wired connection) or need to troubleshoot a failed wireless connection. In many offices, the hub or switch sits on the corner of the desk, enabling the user to see network problems just by looking at the hub or switch.

If the hub or switch also integrates a router for use with a broadband Internet device, such as a DSL or cable modem, you can place it near the cable or DSL modem or at a distance if the layout of your home or office requires it. Because the cable or DSL modem usually connects to your computer by the same Category 5/5e/6/6a cable used for UTP Ethernet networking, you can run the cable from the cable or DSL modem to the router/switch’s WAN port and connect all the computers to the LAN ports on the router/switch.

Except for the 328-foot (100-meter) limit for all forms of UTP Ethernet (10BASE-T, 100BASE-TX, and 1000BASE-TX), distances between each computer on the network and the switch (or hub) aren’t critical, so put the switch (or hub) wherever you can supply power and gain easy access.

Although wireless networks do offer more freedom in terms of placing the switch/access point, you should keep in mind the distances involved (generally up to 150 to 250 feet indoors for 802.11b/g/n) and any walls or devices using the same 2.4 GHz spectrum that might interfere with the signal.

Tip: Decide where you plan to put your hub or switch before you buy prebuilt UTP wiring or make your own; if you move the hub or switch, some of your wiring will no longer be the correct length. Although excess lengths of UTP cable can be coiled and secured with cable ties, cables that are too short should be replaced. You can buy 8P8C (RJ45) connectors to create one long cable from two short cables, but you must ensure the connectors are Category 5 if you are running Fast Ethernet; some vendors still sell Category 3 connectors that support only 10 Mb/s. You’re really better off replacing the too-short cable with one of the correct length.

Current page: Switches For Ethernet Networks

Prev Page Wired Network Topologies Next Page Wireless Ethernet Hardware-

KelvinTy O... I thought all CAT5 are able to transmit 1000Mbps signals BEFORE reading this article... It's kind of weird ~_~" that I can get 5.X MB/s download speed = ="Reply -

Reynod Don could you talk to Chris A and Joe and see if we could give a few hard copies of this book away as prizes for some of our users here in the forums who work hard to help others?Reply

How about a copy for each of the users who make the top ranks for the month of November ... under the Hardware sections of the forums?

:) -

JasonAkkerman They make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.Reply -

xx_pemdas_xx JasonAkkermanThey make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.I got talked into making 10...Reply

-

spookyman JasonAkkermanThey make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.Reply

Oh I don't know. I have made several thousand patch cord over the past 18 years.

All you need is a high quality crimper, good cutters and small screw driver. You are set.

-

silveralien81 This was a great article. In fact it inspired me to buy the book. I'm happy to report that the rest of the book is just as well written. Very educational. A top notch reference.Reply -

neiroatopelcc Read the first page. Seems like well written stuff, but not exactly written for my type of user. Also it seems to be igoring a lot of stuff. For instance it sais the network runs at the speed of the slowest component and will figure it out on its own. This isn't true. If you run a pair of 1000TX capable nics on old cat 5 cable (without the e), it'll still attempt to run at that speed, despite the massive crc errors it might generate. Also, if you're running on 'old gigabit hardware' it won't nessecarily have support for 10Base-T speeds. Also, not all firmware has autonegotiate or automdix support, thus you sometimes have to specificly set the speed between links. This is mainly for fiber links though, which seem to have been ignored entirely.Reply

Anyway. As I said, I think it's well written and probably quite suitable for people who don't know anything about networks (except it seems to assume people know the osi model). I'll go see if the other chapters are equaly basic.

Most Popular