The Race To The Bottom Travels Without DRAM: Low Cost SSDs

The Race to the Bottom is a term used in many industries, and in some situations it's not a favorable phrase. When it comes to SSDs, though, it means providing products that are capable of shipping in large volume and in low cost solutions. It's not a secret that very low cost notebooks and even Chromebooks outsell even moderately priced models with more features and more powerful components. Traditionally, low cost notebooks ship with hard drives, but SSD manufacturers want an increased presence in that space.

Even though retail products like the Mushkin Reactor have driven retail SSD prices down dramatically over the last year, the cost is still too high for adoption in entry level solutions. A recent report by TrendForce showed that OEMs currently pay around $50 for an OEM 128 GB SSD, down from $77.20 one year ago.

According to the same report, SSDs will ship in 30 percent of notebook products this year, with that number surpassing 70 percent by 2017. Most of the recent growth comes from triple-level cell NAND flash, but in order to continue the trend, further reductions are necessary. NAND flash makes up the majority of the cost on an SSD, but DRAM used to cache page table data also plays a significant price role.

SSD controller makers have started to increase processing performance of the controller to accommodate higher levels of ECC technology and at the same time increased SRAM in the controller. Next-generation products designed for OEM customers are powerful enough to remove the expensive DRAM package and manipulate all of the page table data from flash.

The flash technology plays a role here as well. Native TLC performance is low by nature, but pseudo-SLC technologies that mimic SLC flash functions greatly increase low block size performance. This allows SSD markers enough small block transfer performance to remove the DRAM, thus lowering costs.

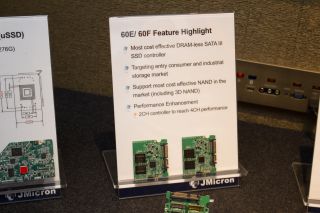

At Computex 2015 we saw controllers that fall into this category from JMicron, Marvell, Silicon Motion Inc. and Phison. The image above shows JMicron's JMF60E DRAM-less solution in three capacity sizes: 32 GB, 64 GB, and 128 GB. JMicron told us the that the JMF60E paired with Micron L95B NAND flash in a 2-channel configuration can read data at 518 MB/s and write sequential data at 139 MB/s.

The performance is light compared to mainstream PC SSDs but significantly higher than hard disk drives. That becomes even more apparent when looking at random performance. The JMF60F delivers up to 12,500 random read IOPS and 21,500 random write IOPS. Hard disk drive random performance still barely breaks 100 IOPS in both read and write random operations.

Stay on the Cutting Edge

Join the experts who read Tom's Hardware for the inside track on enthusiast PC tech news — and have for over 25 years. We'll send breaking news and in-depth reviews of CPUs, GPUs, AI, maker hardware and more straight to your inbox.

Chris Ramseyer is a Contributing Editor for Tom's Hardware, covering Storage. Follow him on Twitter and Facebook. Follow Tom's Hardware on Twitter, Facebook and Google+.

-

fynxer Öhhh, where is the conclusion of the analysis?! You rant through out the article that it will be cheaper when the so called expensive DRAM module is removed. Anyone with half a brain can comprehend that it will be cheaper BUT by how much. How big will the impact on the price be, like approximate or in the neighborhood of or anything. Not just say nothing and leave everybody hanging.Reply -

shrapnel_indie When you get into netbooks and chromebooks, people just want something cheap that works. If its faster than HDD tech it is a plus, but not something actively sought out by the average consumer of these products.Reply

So how much of a performance hit is there?

Will these changes work their way into higher capacity SSDs?

What are the estimated savings with this? (A repeat of fynxer's valid question.) -

Bobs Your Uncle The question about DRAM (materials) cost savings is a good one & I too would have appreciated perhaps a bit more depth in general. It's an interesting topic.Reply

That said, in large scale fabrication & manufacturing, a couple of cents here or there quickly extends to volumetric savings that can easily build to 10's or 100's of thousands of dollars depending on the discipline.

This is, of course, only in direct materials cost & doesn't take into account savings in tangentially related areas, such as the impact of needing to finance smaller outlays, inventory carrying costs across a now smaller array of sku's, etc.

All told, we're talking real money ... if that was truly the point the point of the comment.

If the point, rather, was simply to be glib & demeaning to the author, then cash obviously isn't a concern. -

CRamseyer I thought I posted in this already but apparently not.Reply

Here is the deal, so the article says DRAMless but that just doesn't mean no RAM without other changes. As we all know RAM prices change every day, the same with NAND flash. Even if I put my finger on a price right now and say the DRAM costs 12 Dollars, it would change tomorrow, or more likely an hour later.

Look at it as a package. The flash controller doesn't need the channel running to the DRAM so that is one cost savings. The PCB needs less surface area, more savings. Then the actual DRAM.

On most 512GB SSDs the DRAM density is 1GB. Most of the time we're talking about LPDDR3. I just popped over at Newegg and found real LPDDR3 in a DIMM that costs around 8 Dollars per GB.

Looking at it with a microscope isn't really the way to do it. The target price is $50 for a 256GB SSD. I didn't write about it in this article but I've talked about it in several reviews over the last few months.

Most Popular