FBI-Apple Case Ends With FBI Unlocking The Shooter's iPhone

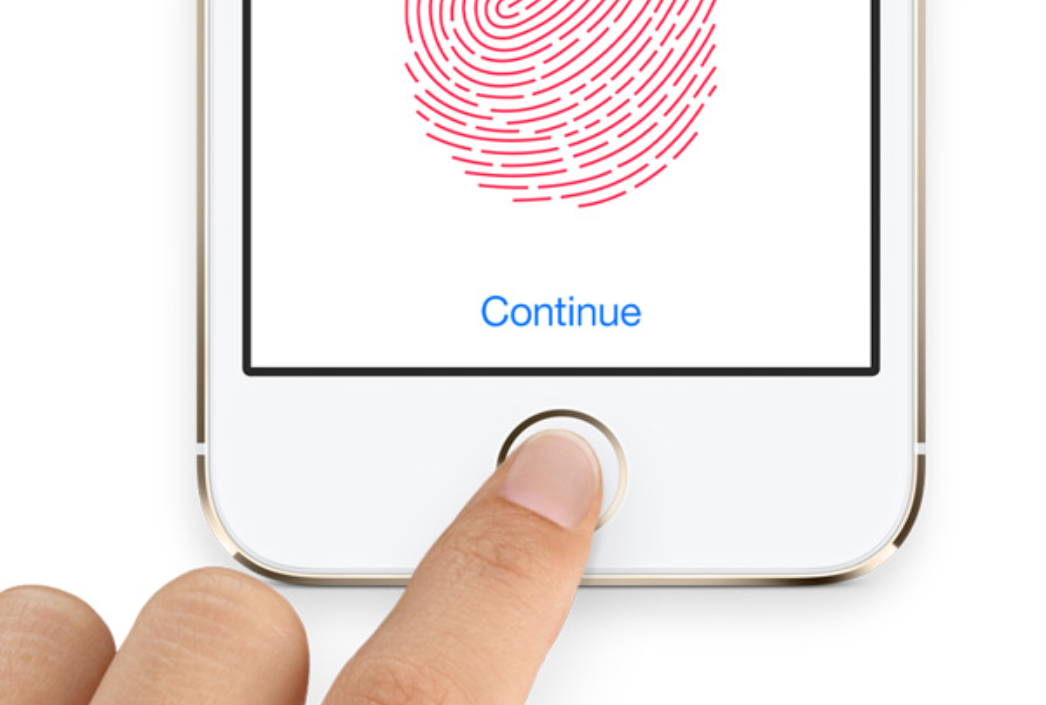

The San Bernardino-Apple case, in which the FBI demanded Apple's assistance in unlocking the gunman's iPhone 5c, ended with FBI investigators saying that they were able to unlock the device without Apple's help.

The FBI found another way to unlock the device after several months during which the agency kept saying that the phone could only be unlocked with Apple's help. This was despite multiple experts and representatives urging the FBI to look for another way, as it is required by the All Writs Act.

Just one day before the courtroom hearing, which was supposed to be held on March 22, the FBI requested that the hearing be postponed until April 5, as the agency was evaluating another method of unlocking the iPhone with the help of a third-party. The FBI investigators on the case never said who that third-party was. Some reports showed that it may be the Israel firm Cellebrite, a provider of mobile forensics software, but the company itself has not confirmed this.

The FBI filed a status report yesterday telling the judge that Apple's assistance is no longer necessary. The report stated:

"The government has now successfully accessed the data stored on Farook's iPhone and therefore no longer requires the assistance from Apple Inc. mandated by Court's Order Compelling Apple Inc. to Assist Agents in Search dated February 16, 2016."

The FBI investigators have not disclosed what was found on the phone, and at this point it is still unclear if there was anything that warranted the search. Many are wondering whether the highly publicized fight between the agency and Apple was even worth it. FBI has denied that it was trying to set a precedent so that other government agencies could later demand the same kind of assistance from Apple to unlock iPhones involved in other cases. However, many other law enforcement officials have said the exact opposite, that they were indeed waiting for this case to conclude so they can use the precedent in their favor.

Nonetheless, a recent New York case already set a precedent for similar cases, agreeing that government agencies and officials can't compel Apple to unlock its devices. Therefore, although it's unlikely that this is the last time that the FBI demands assistance with unlocking iPhones, Apple will already have a precedent on which to rely on.

Companies that use strong encryption in their products and services will also need to be more vigilant in the future; the FBI and other U.S. government agencies will likely try to not make these cases public anymore. Many similar cases have not been disclosed in the past, so we don't know whether some companies may have helped law enforcement agencies or not.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

EFF, OTI Ask For Disclosure

The EFF said that the FBI should tell Apple what the vulnerability was that allowed it to unlock the phone. An anonymous law enforcement official told CNN that it's still too early to know whether the same vulnerability can work on other iPhones.

The EFF said that according to the Vulnerabilities Equities Process (VEP), which is the government's own policy for how it deals with disclosing vulnerabilities, the FBI must disclose the vulnerability if it affects just this one phone, but especially if it can affect other devices. As part of its mission to increase public safety, it's FBI's responsibility to help Apple fix the flaw in its devices, but this also seems to be strongly encouraged by the administration's own executive policy.

Ross Schulman, senior policy counsel at the Open Technology Institute (OTI), also said that if the vulnerability isn't fixed, other nations could hack into Apple's iPhones the same way; it's the U.S. government's duty to disclose the vulnerability to the company:

"The bug is, so far as we know, widely distributed and can give complete access to a device that so many of us rely on daily. Those are great reasons to tell Apple so they can fix the problem," Ross Schulman told CNN.

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware. You can follow him at @lucian_armasu.

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He covers software news and the issues surrounding privacy and security.

-

hdmark I think a great ending to this story would be the FBI actually letting Apple know the vulnerability. Then apple fixes it, and we have another fun case in a year :DReply -

Kenny Schneider Doesn't this feel a little hypocritical? Apple didn't want to help unlock it and told the US Govt. to sit and spin. Then the US Govt. unlocks it and they're supposed to tell Apple how to stop it in the future. Then, when a similar issue happens and the government has a right to the evidence via a warrant, won't this battle be doomed to repeat itself?Reply -

ahnilated ReplyDoesn't this feel a little hypocritical? Apple didn't want to help unlock it and told the US Govt. to sit and spin. Then the US Govt. unlocks it and they're supposed to tell Apple how to stop it in the future. Then, when a similar issue happens and the government has a right to the evidence via a warrant, won't this battle be doomed to repeat itself?

This case was NEVER about just one phone no matter what the FBI stated. This was about setting case prescience so they could get into any phone whenever they wanted.

-

hst101rox WHo knows, might not of been a bug. Maybe they took out the encryption chip and took layer by layer off until they could use special instruments to read the silicon to get the key. That was 1 method I remember was possible.Reply

Or McCoffee found a vulnerability.

EDIT: Or an israeli firm.. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-encryption-cellebrite-idUSKCN0WP17J -

xHDx ReplyDoesn't this feel a little hypocritical? Apple didn't want to help unlock it and told the US Govt. to sit and spin. Then the US Govt. unlocks it and they're supposed to tell Apple how to stop it in the future. Then, when a similar issue happens and the government has a right to the evidence via a warrant, won't this battle be doomed to repeat itself?

No, this is the problem with organisations interfering with technology they don't have a clue about. It's not right that the government can decide on issue that they don't understand. The FBI wanted access by using the laziest technique possible which is asking for a backdoor. That's a clear definition of how an organisation has no idea about the tech they're trying to handle. It's a disgrace.

-

Math Geek i'm glad they did it on their own but sadly we know next year they will be back with a new phone and a new request and it'll start all over.Reply

this is how it should be, the fbi and the rest should crack what they can and then suck it up for what they can't. same as everyone else who wants to hack something. the question is whatever way in they found, is it still there in newer models and os versions? this is what we don't know much about yet. it had to be a hardware vulnerability and i know apple has steadily gotten the hardware itself more secure so it remains to be seen if this is still available to newer devices. -

Chris Droste ReplyDoesn't this feel a little hypocritical? Apple didn't want to help unlock it and told the US Govt. to sit and spin. Then the US Govt. unlocks it and they're supposed to tell Apple how to stop it in the future. Then, when a similar issue happens and the government has a right to the evidence via a warrant, won't this battle be doomed to repeat itself?

No, This is the government's own policy about disclosing vulnerabilities in a secure digital system. Originally the FBI was trying to coerce Apple into making a scriptkiddie cracker tool by using an old old 1800s-era evidence gathering policy never meant to encompass the digital era. it wasn't even the FBI itself that actually cracked the phone; it's very likely a 3rd-party firm working for a foreign government, which would even make it more in the US's interests to see to it that Apple gets information on this vulnerability considering it's still one of the only phones on the market with the Dept.of Defenses' coveted "Authority to Operate" seal of approval..

-

turkey3_scratch I actually heard from another source how they did it. Apparently, they managed to disable the feature that wipes the phone after 10 failed attempts, so once that was disabled, they were able to punch in the code until they got it right. Yes, it was someone's job to punch in a gazillion codes until it was right most likely. How fun :PReply