How The FBI Dodges Compliance With The ‘Vulnerability Equities Process’

After refusing to disclose the vulnerability that was used to hack the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone, the FBI thought it could make up for that by disclosing another iPhone and Mac vulnerability to Apple. There was only one problem: The bug had already been reported to Apple by other parties, and it was already fixed nine months ago.

Vulnerability Equities Process

The FBI must comply with the Vulnerability Equities Process (VEP), which says that the government must not withhold “major” security vulnerabilities from the companies affected by them, with few exceptions.

The VEP policy was put in place in 2010 but enforcement likely began more seriously only in 2014, following Snowden’s revelations and accusations that the government stockpiles zero-day vulnerability for use in surveillance and sabotage.

Last year, the NSA said that it discloses the most serious software flaws “90 percent of the time,” but it didn’t say how long it holds that information before it reports them to the companies. It could very well disclose them after they were already reported by other parties, or even fixed by the vendors of the software products, similarly to what the FBI is doing right now.

FBI’s VEP Loophole

Because the vulnerability being used by the FBI in the iPhone hack could also be used by other hackers to crack potentially millions of other iPhones, the FBI would normally have to disclose it under the VEP policy. However, the FBI may have found a “loophole” in this policy, and it intends to tell the Obama administration that it can’t disclose it because the hack was done by a third party with which the FBI isn’t familiar.

On the face of it, this argument may make some sense, although it’s a little hard to believe that after the FBI has already said it can use the same hack to unlock other iPhones as well, it’s not at least somewhat familiar with how it works.

Court Order-Proof Investigative Techniques?

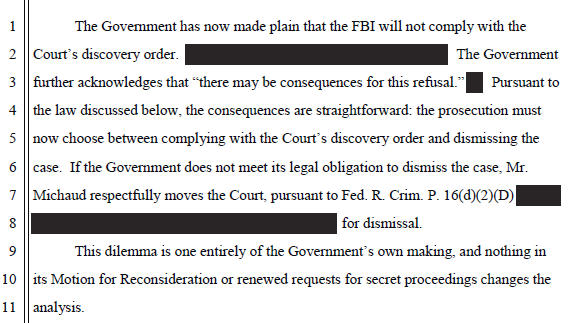

If we do take at face value the FBI’s argument, then we can assume that when the FBI is familiar with the vulnerabilities, then it should be able to report them. However, this doesn’t seem to be happening, either. In some other cases, the FBI and the Department of Justice are disobeying even direct orders from the courts to reveal the exploits. Instead of revealing their methods, they prefer to drop the cases altogether.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

According to the ACLU, the FBI has instructed police departments to hide the use of cell tower simulators from courts. When asked about the source of the information, the police officers were told to say that they got the suspect’s location from “unknown sources.” As it turns out, the FBI had good reason (from its perspective) to try and hide this type of technology, because multiple judges later ruled that such investigation techniques require a warrant.

In another recent case, involving an exploit of Mozilla’s Firefox browser (on which the Tor browser is based), the government again preferred to drop the case instead of complying with the Court order and revealing its hacking methods.

The government's position is interesting when one considers that only recently, the FBI was talking about "warrant-proof" iPhones and saying that Apple is acting like it was above the law because it refused to comply with a Court order. The latest draft of the anti-encryption bill co-sponsored by Senators Dianne Feinstein and Richard Burr also includes text that says "nobody is above the law", and therefore companies must decrypt information when asked to do so. However, it doesn’t look like the government wants to lead by example in complying with Court orders.

The FBI is unlikely to ever reveal the vulnerability used to hack the iPhone in its case against Apple, at least not until it has stopped working. However, if it wants to be seen as properly complying with the Vulnerabilities Equities Process, it will have to actually reveal software flaws that weren’t previously reported (if it does find such flaws).

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware. You can follow him at @lucian_armasu.

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He covers software news and the issues surrounding privacy and security.

-

JamesSneed Is it just me or does it seem it was never about cracking the iphone? In fact I wonder now if the FBI ever did crack the phone? It seemed they wanted to set a precedent until Apple full out refused and lawyerd up. Realizing they would very likely loose the precedent setting case they "cracked" the phone in time not to need to go to court. All of that just seems a little convenient. We will probably never know.Reply

Edit: For those that don't recall the iPhone that was being cracked was his "work" phone as his other phone was destroyed on purpose. When you are going to be caught and you destroy only your personal phone its not a long stretch to assume no terrorist activity was on the "work" phone. This is why I went down the rabbit whole in the first place as it never really seemed like there would be anything of importance on the phone anyhow. -

Onus Anyone who thinks the US Federal Government will not duck, ignore, or subvert any law it finds inconvenient has not been paying attention for the last fifteen years (at least).Reply -

Tykkopoles ReplyAnyone who thinks a government will not duck, ignore, or subvert any law it finds inconvenient has not been paying attention for the three thousand years.

FIFY -

mamasan2000 The state and government was created by who exactly? The people? Of course not. Corporations created it. Pretty neat setup. Tax payers pay for everything, corporations get the benefits.Reply -

toadhammer ReplyAnyone who thinks the US Federal Government will not duck, ignore, or subvert any law it finds inconvenient has not been paying attention for the last fifteen years (at least).

Try 80 years, or even longer. Congress has traditionally exempted itself from any workplace-related laws it passes. Some of these have changed, but traditionally things like healthcare, insider trading, discrimination, and for staffers workweek, wage, overtime, OSHA, etc. They're pretty much self-entitled bastards. -

JamesSneed Reply17883612 said:The state and government was created by who exactly? The people? Of course not. Corporations created it. Pretty neat setup. Tax payers pay for everything, corporations get the benefits.

Well it was created by and for the people then Citizens United ruling came in an F***ed it up. -

jeremy2020 Reply17883612 said:The state and government was created by who exactly? The people? Of course not. Corporations created it. Pretty neat setup. Tax payers pay for everything, corporations get the benefits.

Well it was created by and for the people then Citizens United ruling came in an F***ed it up.

To be fair, it was messed up before Citizens United. That ruling has just sped along the process of getting to a bloody, violent revolution. -

scolaner ReplyIs it just me or does it seem it was never about cracking the iphone? In fact I wonder now if the FBI ever did crack the phone? It seemed they wanted to set a precedent until Apple full out refused and lawyerd up. Realizing they would very likely loose the precedent setting case they "cracked" the phone in time not to need to go to court. All of that just seems a little convenient. We will probably never know.

Edit: For those that don't recall the iPhone that was being cracked was his "work" phone as his other phone was destroyed on purpose. When you are going to be caught and you destroy only your personal phone its not a long stretch to assume no terrorist activity was on the "work" phone. This is why I went down the rabbit whole in the first place as it never really seemed like there would be anything of importance on the phone anyhow.

Right. That's been the crux of Lucian's articles on the subject. All about precedent, then backing away when it looked like they would lose so as not to set a precedent that worked AGAINST them.