Rock, Roll 'n Print

Graham Nash's Introduction, Continued

In the early 1980s, with the help of my friend R. Mac Holbert, I began scanning some of my own images into a computer with a Thunderscanner, which was a small scanner head that you put into an Apple Dot Matrix printer in place of the ink cartridge. The item to be scanned was fed into the printer - just like loading paper into a typewriter - and special software activated the print head, which scanned the paper or the image line by line. Playing around with this system was intriguing, but when I began to get serious about the images, I discovered that there was no way to get them off the screen successfully. I tried everything - photographing the screen, thermal prints, and wax prints. There weren't a lot of choices available in those early days.

We also had some very simple image manipulation software called Digital Darkroom. I really wanted to see several of my images in a large size. The search for a large print led us to an organization at UCLA. It was the Jetgraphix workshop, set up with assistance from the Fuji Corporation. I called and spoke with the manager, John Bilotta, and we printed several of my pictures. The results, though exciting, still left much to be desired. The pixels in the images were about the size of a food tray, but at least they were printed on decent paper. John mentioned that he had heard about a printer from Iris Graphics back east that was used to make quality proofs for the printing industry. Around the same time, my friend Charlie Wehrenberg and his brother Paul, who worked for Apple, put me in touch with Steve Boulter from Iris Graphics. Steve was in charge of developing relationships with people - artists in particular - who wanted to use Iris's inkjet printer, and he told me about a company in Los Angeles that used it extensively. Soon after, Mac and I visited the George Rice Company to witness the printer for ourselves. Needless to say, we were very impressed. The image we saw printed that day was still not as pleasing as the technology, yet the process we saw changed our lives. We quickly realized that this "machine" would be able to give us the quality of prints our sensibilities demanded.

My first real experience in the digital printing world was another profound moment in my life. An art director was doing a book on Joni Mitchell, and he knew that I'd taken many images of her. He asked to use them, and instead of having the discipline to separate my shots of Joni from the rest of my images, I sent him all my negatives. I never saw them again. David Coons, a technician then working at Disney, was at my house for dinner one night and saw the box of proof sheets that I had of those missing negatives. I told him the story, and he was as upset as I was, because no artist wants to lose his work. "Do you have a particular image on these proof sheets that you like?" he asked. Pointing to one, I said, "Yes, I like this shot of Crosby." Three days later he came back with an Iris print that knocked my socks off. It had wonderful tonal qualities, a beautiful surface, it was on decent paper, it was in focus, and it was large. Coons had made a scan from a slightly larger than normal-size proof sheet and brought me a print of my image of Crosby that was 20 by 24 inches. It was beautiful, absolutely beautiful. And from that moment Mac and I knew that the digital printing world was full of secrets that we had to unlock.

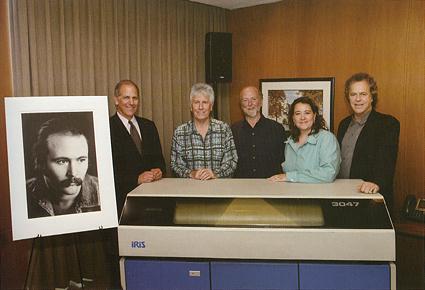

Brent D. Glass, Graham Nash, Steve Boulter, Shannon Perich and R. Mac Holbert at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, August 12, 2005, when Nash Editions' first Iris 3047 inkjet printer was incorporated into the museum's photographic history collection, along with prints from the Nash Editions archive. Note the print of David Crosby that Nash mentions in the paragraph above.

After several conversations about using archival rag paper and the longevity of the inks, I decided to buy the printer. Fortunately, I had just successfully sold a major part of my photographic collection at an auction at Sotheby's, so I decided to take a financial chance and chase a dream based on our intuitions. At that time, an Iris 3047 inkjet printer cost the equivalent of a nice house. Within an hour of getting the printer to the garage at 1201 Oak Avenue in Manhattan Beach, we immediately voided the warranty by sawing off the printer heads and remounting them slightly further away from the drum so we could use thicker paper. A few weeks later, after a great deal of trial and error, we decided to print my first New York show, held at the Simon Lowinsky Gallery in 1990.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Current page: Graham Nash's Introduction, Continued

Prev Page Rock, Roll 'n Print Next Page Graham Nash's Introduction, Continued