China Fires Back at US Sanctions, Officially Restricts Exports of Chipmaking Materials Gallium and Germanium

Makers of components featuring gallium seek to diversify their supply.

China on Tuesday officially implemented its export regulations on gallium and germanium-related products, a decision that many consider a retaliation for restrictions imposed on the Chinese semiconductor sector by the U.S., Japan, and the Netherlands in the recent quarters.

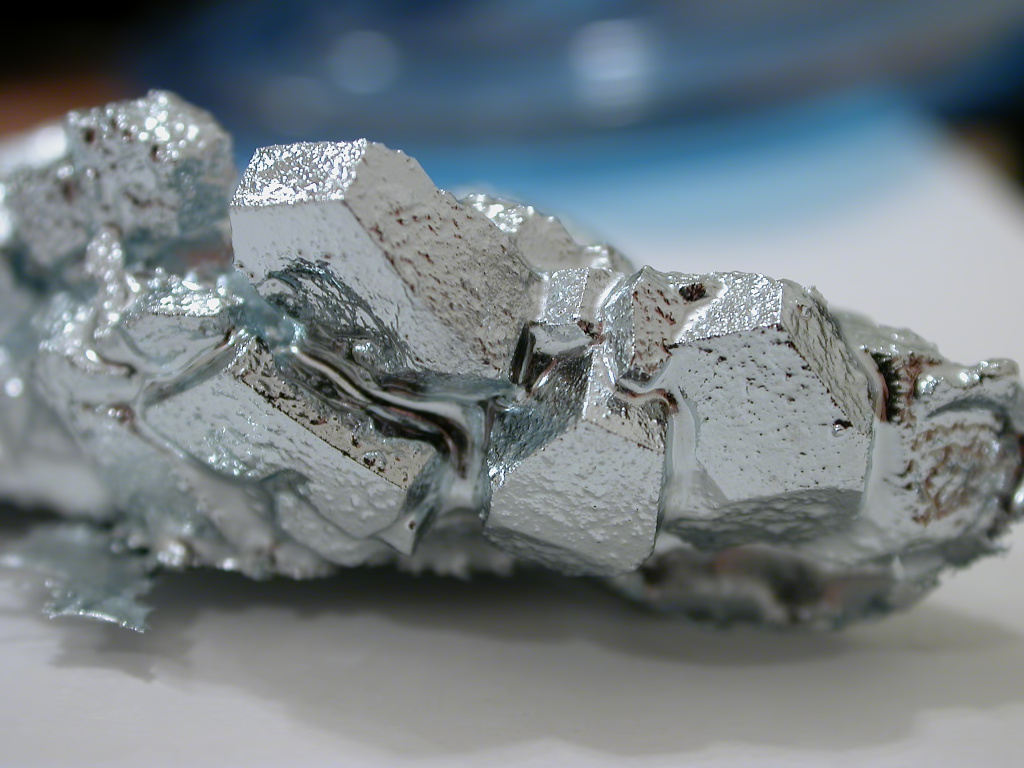

Starting August 1, 2023, Chinese companies must obtain an export license to export gallium and germanium metals, as well as any products containing these elements. According to various researchers, China controls 94% or more of the global gallium production and around 60% of the global germanium output. The new export rules could potentially impact Japan's chipmaking industry, which relies on China for 40% of its supply, according to Nikkei.

The announcement of the curbs in early July caused a surge in gallium prices by nearly 20% in the U.S. and Europe. This new rule is said to be implemented in the interest of China's national security but is considered a response to restrictions against the Chinese high-tech industry.

Japan is the world's largest consumer of gallium, according to the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security, which means that these new regulations will impact Japanese companies. Over 40% of Japan's gallium is procured from scrap and other sources, 60% is imported, and 70% of these imports are from China. As a result, around 40% of Japan's gallium supply comes from the People's Republic of China.

Mitsubishi Chemical Group, which produces compound semiconductors and other products, says it has sufficient stock in Japan, negating any immediate supply issues. Other companies, including Sumitomo Chemical (a maker of gallium nitride substrate) and Nichia Corp. (a maker of LEDs), echo similar sentiments, with plans to monitor the situation and consider diversifying their suppliers.

Despite the new regulations, China's Ministry of Commerce asserts that the quality and quantity of these exports will not be affected. As long as exporters adhere to the national security protocol and other regulatory criteria, exports will continue. So far, the new controls have not impacted Japanese companies' raw material procurement or other business activities.

Notably, this development follows the 2019 decision by the Japanese government to restrict chipmaking materials exports to South Korea. This has provoked strong opposition from China, which has experienced curbs on advanced semiconductor exports from the U.S. and Japan. Wei Jianguo, former vice minister of commerce in China, warns that these export controls on gallium and germanium might be just the beginning of retaliatory actions. In the future, China may further leverage its dominance in certain commodities as a tool for economic and diplomatic pressure.

Despite gallium and germanium not being particularly rare and often being procured as byproducts of other mining activities, their low prices have been supported by China's cheap refinement process, making the extraction of these metals in other regions unprofitable. The new restrictions imposed by China may initially lead to price rises and potential disruptions in supplies and production of certain components. However, in the long run, these restrictions could motivate companies in other countries to mine these metals, which may eventually challenge China's market supremacy. Interestingly, the Pentagon recently announced plans to recover gallium from waste electronics.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.

-

TechieTwo I don't imagine they can substitute gallium for food so this is a loss-loss deal where no one wins.Reply -

anonymousdude Like the article pointed out, neither material is actually rare just unprofitable to mine. When push comes to shove countries will have to mine it themselves. Naturally, they'll avoid that as long as they can as the cost and environmental impact is steep. More likely what will happen is they'll just buy through an intermediary. Kind of like how things were shipped to Vietnam first, to sidestep US tariffs on Chinese goods.Reply