IndieCade 2012 is Proof Positive that Games Are Art

This was my first time attending IndieCade... and I was thoroughly impressed.

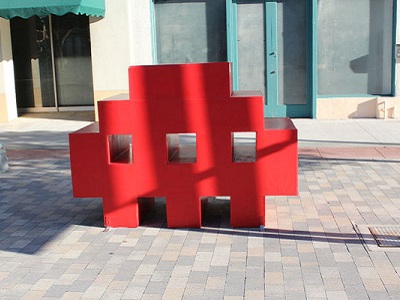

Last weekend, IndieCade, a festival dedicated solely to independent games, kicked off its Festival Day in downtown Culver City, California. The festival, open to the public (for the most part), was scattered between various and sundry venues along a two-block stretch of the downtown area.

As a first time attendee, I'm not quite sure how to accurately paint a picture of the festival. IndieCade isn't your run-of-the-mill videogame convention. It's not a weekend of wandering an expansive convention center filled with extravagant booths. Keynote speeches, playable demos, and board games were all hosted under small white tents manned by volunteers, who staffed the entire event. By its organization and appearances, IndieCade wins all the indie charm.

There wasn't a major publisher presence, sans Sony, who helped sponsor the event. To its merit, Sony was only there pushing its release slate of smaller, "indie" (to use the term flexibly) downloadable titles. The PS Vita, which has thus so far been shafted by Sony at almost every trade show conference, dominated the tent with an impressive lineup, one that may have boosted sales had Sony pushed them a little harder.

As someone who ran around the event with press privileges, I found IndieCade to be refreshing. IndieCade is in the paradoxical position of being both pretentious and yet lacking pretention at the same time. This is the same festival where you'd hear developers deride triple-A gaming as pure drivel, highlighting especially how much they just hate, hate modern shooters, and yet be the same place where there's no discrimination between those holding press badges and those without. Rather than having to jump through the hoops and ladders of dealing with public relations and a mess of NDAs and legal gag orders, any curious bystander could approach a developer with questions.

At the risk of sound like some sort of videogame elitist, I saw more that impressed me at IndieCade than I've seen at most major tradeshows, despite most of the games being unfinished or in their alpha stage. As part of the pains of working in the entertainment industry, developers and publishers are under pressure to bring out content that targets the widest audiences for profit margins. Indie developers, under no such duress, are free to churn out content in line with their passions… and so, logging through player-unfriendly UIs and unintuitive controls are an integral part of the IndieCade experience.

And yet, despite the lack of polish and the flaws in almost every game, I thoroughly enjoyed myself. To those who continue to scoff at the notion that videogames can be art: I point you towards this festival.

Almost every game attempted to experiment or play with the forms of game design in some way. Rob Lach's POP: METHODOLOGY EXPERIMENT ONE, for example, is a series of different vignettes without any sort of rhyme or reason that left the player reeling with confusion attempting to seek a deeper meaning, despite there not being one… maybe. On a less perplexing level, James Roberts' Gorogoa toys with the player's sensibilities on space and depth by shifting between four different tiles of seemingly different images that need to be shifted and overlaid to proceed in the game.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Others, such as David Scamehorn and Alexander Baard's Super Space ____and Ramiro Corbetta's Hokra, demonstrate how even the simplest designs could induce meaningful play.

There's a certain vibe not present in larger videogame conventions that's an integral part of IndieCade. It manages to seek out and bring to the public some of the most innovative work that simply cannot exist within triple-A game development that's so heavily-entrenched in business. In part due to readily-available tools, digital distribution, and social media, the indie gaming scene is burgeoning. I wouldn't be surprised if IndieCade were to grow in prominence and esteem as a festival in the coming years, though I hope it never loses that unbridled sense of passion for games development that makes the conference so unique.

Catherine Cai was a freelance news writer for Tom's Hardware. She covered a variety of tech industry news, ranging from PC components to PC and console gaming.

-

Shin-san The reason why I feel that games are art is simple: because they declare a lot of crappy stuff in the name of art. There's not a high barrier of entry into the world outside a bunch of pretentious blowhards that are in charge of what is and is not called artReply -

Azimuth01 I've always believed games are a form of art. The people who build these virtual worlds use creative vision that employs aspects of every art from imaginable. Music, modern design, classical Renascence paintings, fashion...every form of artistic vision has a foothold in game design.Reply

With that said, I cant understand for the life of me why rigid business men in suits and ties with loyalties to stockholders and their board of directors are making artistic decisions. These same people then wonder why their stock prices are going through the floor (EA?). -

ChromeTusk For some reason, I kept thinking about the differences between Blizzard's earlier days versus how they look and operate now.Reply -

bigdog44 Art is in the eye of the beholder. Hopefully these indie guys arent afraid of bullies.Reply -

back_by_demand Depending on your viewpoint, everything is art, videogames are no differentReply

...

Just like painting, for every Van Gogh, there is a worthless scrawl and it's good to see EA sitting at the scrawl end whilst the unknown Indie guys are boshing out a "Sunflowers" for future generations -

bearracuda bigdog44Art is in the eye of the beholder. Hopefully these indie guys arent afraid of bullies.Reply

I'm sure they can take it. There are a couple of things you need to be indie. You need backbone, to fight through a disorganized and rocky development process, where you're not sure you'll have the same guys working with you each day. You need to have guts, to keep going even when everyone says you're an idiot and you're wasting your time. And more than all that, you need passion. You need to love the games and the gamers more than anything else in the world. That's why indie devs can churn out innovation and creativity the way they do.

They really only have 1 person to answer to: the player. And that's the way it should be.

-

Japan has had something like this for awhile now. They call it Comiket. It is a semi-yearly event held in Tokyo that attracts over 600k visitors over the course of three days. Last summer they held Comiket 82. Granted, the focus is on manga and music, but there a quite a few indie game developers there as well. I've been following Comiket since C70 and I've seen several interesting titles released during Comiket (ex. Recettear: An Item Shop’s Tale was released during C73).Reply

Anyways, check it out if it sounds interesting to you.