AMD Challenges Intel's NUC, Fosters Mini PC Ecosystem

AMD is broadening its assault on Intel with a new line of Mini PCs

Today AMD announced that it is fostering an ecosystem of Mini PCs that allow the company to attack Intel's NUC (Next Unit of Computing) segment.

AMD's return to glory has centered on its Zen microarchitecture, and its inherent scalability allows the company to use the same underlying design to challenge Intel in multiple segments that span from the desktop to the data center. That approach has proven to be incredibly effective as the company takes market share from Intel in several key segments, but the company's beachhead in the desktop PC market gives it firm footing to begin an assault on other segments, like Intel's NUC (Next Unit of Computing).

Intel's NUCs are small 'mini PCs' themselves, with fully-contained systems that often dip down to smaller than a liter. Intel designs and sells the motherboards for the barebone systems, and you can also order NUCs with components already installed, like memory and storage, from third-party retailers. However, the term 'NUC,' which is short for Next Unit of Computing, is an Intel branding for those small systems, so AMD has officially embraced 'Mini PC' branding, although a few of its partners are using NUC naming conventions for their products.

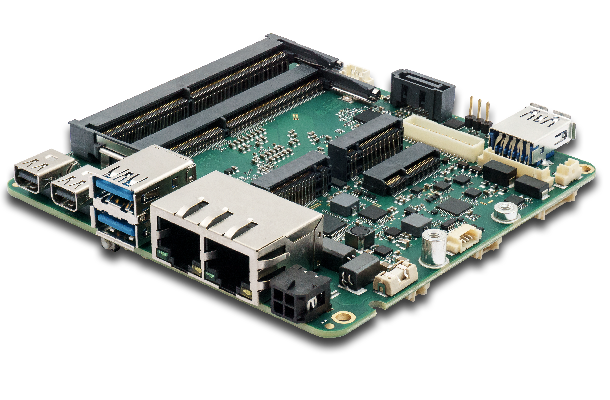

Unlike Intel's approach with NUCs, which involves creating the motherboards and selling them to third-party vendors that add their own differentiating features, AMD's Mini PC efforts consist of enabling an ecosystem of partners to use its Ryzen Embedded V1000 and R1000 processors as the linchpin for their own designs.

We have already seen several of the new devices pop up at retailers like ASRock and Simply NUC, and now EEPD and Onlogic have joined the ranks of companies offering their own Mini PCs.

Like the NUC ecosystem, these initial designs target the media, industrial, communications, and enterprise markets. Although the chips are already used for several handheld gaming devices, they haven't quite spread as deeply into the consumer PC space yet.

Vendors have based the leading-edge devices on AMD's Ryzen Embedded V1000 and R1000 SoCs, which might limit the initial uptake in the consumer market.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

| Ryzen R1000 - Banded Kestrel | TDP | Cores / Threads | Base / Boost Freq. (GHz) | GPU Compute Units (CU) | GPU Freq. (GHz) | L2 Cache | L3 Cache | Memory Support | Dual Ethernet Ports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1606G | 12W - 25W | 2 / 4 | 3.5 / 2.6 | 3 | 1.2 | 1MB | 4MB | Dual-Channel DDR4-2400 | 10Gb |

| R1505G | 12W - 25W | 2 / 4 | 3.3 / 2.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 1MB | 4MB | Dual-Channel DDR4-2400 | 10Gb |

AMD's R1000 series come as BGA-mounted SoCs, meaning they won't install in a normal desktop PC motherboard, and feature Zen+ CPU cores paired with the Vega 3 graphics engine. This class of chips drops into any number of devices, like the handheld Smach Z gaming PC, the Atari VCS, robots, digital signage, industrial, thin client, and networking equipment.

The R1000-Series processors slot in under AMD's quad-core eight-thread V1000 models. To maximize compatibility, both the R1000 and V1000 chips can be attached to FP5 BGA motherboards, but they also come paired with AMD's Zen+ cores and Vega graphics engine. Together, these two classes of chips address the 6W to 54W TDP range of the market. As expected of devices that address these segments, AMD will make the processors available for 10 years.

For now, AMD is working with these OEMs on the leading edge products to enable its MiniPC ecosystem, but newer versions of these models will logically come paired with the Zen 2 microarchitecture based on the 7nm process paired with either the Vega or Navi graphics engine. That will naturally widen their scope, thus becoming a class of processors that could gain deeper penetration into the consumer PC market.

Sticking to its roots, AMD supports pre-validated open source software packages, like Radeon Open Compute (ROCm) and OpenCL. We expect that this initiative will expand over time to include other vendors, and to see more consumer-friendly PC versions of these products emerge.

Paul Alcorn is the Editor-in-Chief for Tom's Hardware US. He also writes news and reviews on CPUs, storage, and enterprise hardware.

-

logainofhades AMD is really taking the fight, to Intel, on all fronts. Competition, in every segment, at last.Reply -

Sn3akr I think You goofed up the spreadsheet.. According to that, base clock is higher than boost clock :unsure:Reply

Anyways.. It's awesome that AMD is coming up with an alternative to the NUC-series from Intel, and we finally get some competition on that market aswell. I'll be looking forward to seeing some reviews of theese things. -

Co BIY Is this a viable segment though ? I feel like I've seen Intel cancel product after product in this area.Reply

I think the Intel concept that includes vertical integration could make low end end desktops for emerging markets profitable enough to build but even that space is probably going to be (or has been ) leapfrogged by phones and tablets.

I can see a market for Phone "docks" that allow you to connect a mouse, keyboard and workable large monitor to your powerful, connected and expensive smart phone. -

Rdslw That's almost what I wanted.Reply

I wanted AM4 in SFF as possible, I dont even need the PCIE x8/16 line. (I would not mind 3 or 4 m.2 slots though) Something small enough to mount behind monitor AND powerful enough for weekend gamer.

And this is it. Memory is damn slow, but its manageable and I probably won't have a chance to buy it. -

TCA_ChinChin Awesome to see competition from AMD in this aspect. It'll be a tough fight since Intel has been entrenched in this market since its inception, but this can only mean more choices for consumers.Reply -

logainofhades ReplyRdslw said:That's almost what I wanted.

I wanted AM4 in SFF as possible, I dont even need the PCIE x8/16 line. (I would not mind 3 or 4 m.2 slots though) Something small enough to mount behind monitor AND powerful enough for weekend gamer.

And this is it. Memory is damn slow, but its manageable and I probably won't have a chance to buy it.

The Asrock A300 desk mini is the closest solution for you, depending on your gaming needs/desires. Can pair it with any AM4 APU.

https://www.newegg.com/p/N82E16856158064 -

Geoffrey Swenson I've wanted a really portable but reasonably fast computer. This might be a good way to go for me.Reply -

jbheller ReplyRdslw said:That's almost what I wanted.

I wanted AM4 in SFF as possible, I dont even need the PCIE x8/16 line. (I would not mind 3 or 4 m.2 slots though) Something small enough to mount behind monitor AND powerful enough for weekend gamer.

And this is it. Memory is damn slow, but its manageable and I probably won't have a chance to buy it.

Get one of these. You won't be disappointed.

https://www.asrock.com/nettop/AMD/DeskMini%20A300%20Series/

The stock cooler fits in the case too. You just have to remove the top shroud off the cooler, which is held on with a couple of philips head screws. -

jbheller ReplyGeoffrey Swenson said:I've wanted a really portable but reasonably fast computer. This might be a good way to go for me.

https://www.asrock.com/nettop/AMD/DeskMini%20A300%20Series/ -

Rdslw Reply

I know but it's sold ONLY with intel in my country :)logainofhades said:The Asrock A300 desk mini is the closest solution for you, depending on your gaming needs/desires. Can pair it with any AM4 APU.

https://www.newegg.com/p/N82E16856158064