Tech Companies Reject GCHQ’s Proposal to Undermine Encryption

A group of 47 companies, including Apple, Google, Microsoft and WhatsApp (Facebook) criticized a proposal by UK’s GCHQ spy agency to eavesdrop on encrypted messages. The group argued that GCHQ’s proposal would undermine everyone’s trust in messaging platforms, the security of those users, as well as their privacy and freedom of expression rights.

GCHA's "Ghost" Proposal Spooks Tech Companies

Last fall, two GCHQ representatives published the “ghost” proposal, which involved allowing spy agencies around the world to act as “ghosts” that participate in users’ private conversations. The companies would also have to suppress client-side notifications that would normally warn users of a new party entering a conversation.

The open letter published by the tech companies’ coalition with civil liberties groups as well as other security experts have called this idea an exploitation of weakness in most encrypted communications platform.

The only way GCHQ’s suggestions could work is if the messaging platform vendors modify the authentication process for their private communication platforms, which the coalition argues would undermine both users’ security and trust in said platforms. The authentication process allows users to trust that they are talking to the right people.

Although the writers of the ghost proposal argued that the encryption protocols wouldn’t be touched, security researcher Susan Landau previously wrote that the changes would still create a much more complex system that would be prone to its own security issues; in this system, the negotiation of encryption keys would have to accommodate the silent listener (the spy agency operative, in this case).

Most Encryption Systems Theoretically Vulnerable to Ghost Proposal

Currently, most communications platforms that use encryption could be vulnerable to GCHQ’s ghost proposal, because they don’t use proper end-to-end encryption that keeps the conversation only between the sender and the receiver.

For instance, communications encrypted only with the HTTPS protocol normally allow the company’s server to read those conversations. This is how Google is able to target you with ads based on your Gmail conversations. If Google couldn’t access those messages in plaintext, it wouldn’t be able to read them.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Gmail emails are encrypted between Google’s own servers, as well as between Google’s servers and most other email providers that have adopted the same encryption standards. However, Google and those other email providers can also see your emails in plaintext -- it’s just no one else that can do that (unless they hack the email servers).

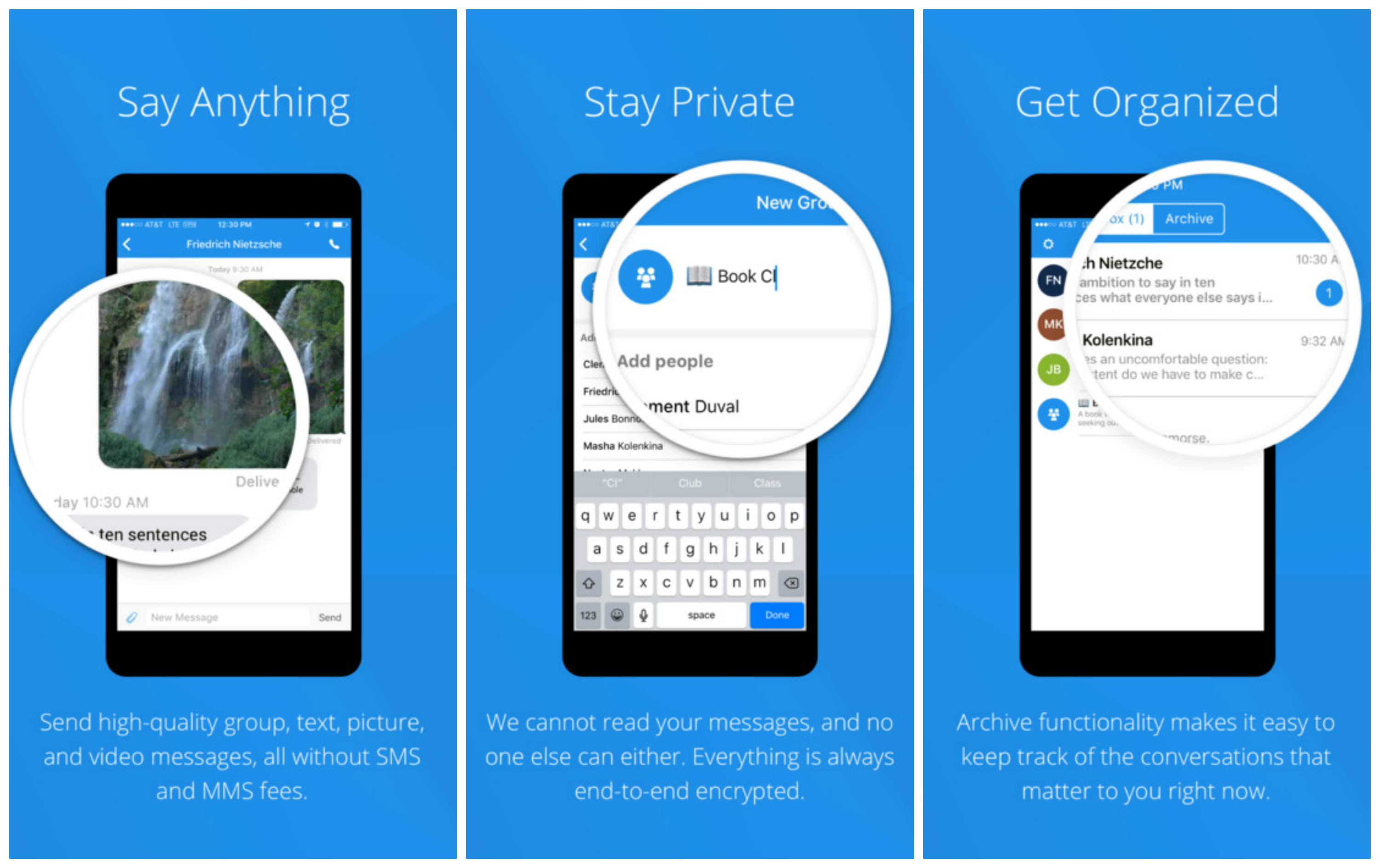

On the other hand, properly end-to-end encrypted communication solutions, such as the open source Signal messenger, an end-to-end encrypted email service such as ProtonMail, or simply using PGP, allow only the sender and the receiver to access the messages. Some end-to-end encrypted services such as Apple’s iMessage or Facebook’s WhatsApp do pretend to to offer end-to-end encryption, but it comes with some caveats.

For example, although Apple may not directly be able to read its customers’ iMessages, the company manages the encryption keys in a conversation between users and can add itself -- or anyone else -- to that conversation, either as a visible party or an invisible one. Apple also stores most of its customers’ iMessages by default on its own servers through iCloud sync.

Facebook has also allowed a weakness in WhatsApp to exist for the past two years with seemingly no intention of fixing it. This security weakness allow Facebook to “re-encrypt” user’s messages with its own keys, supposedly to preserve received messages in case the user is in the process of switching phones or doesn’t have an internet connectivity. Some have called this a backdoor, while others believe that accusation is an exaggeration.

Any Encryption Backdoor Is A Backdoor For Anyone

As a response to the ghost proposal, security expert Bruce Schneier reminded the GCHQ authors that any backdoor in communications platforms, or any kind of remotely administered “lawful intercept” solution would eventually be used by both a country’s adversaries as well as cyber crime groups.

For instance, the GCHQ ghost authors likened their solution to that of adding law enforcement operatives to a call between two people via phone switches that were mandated decades ago for the purpose of surveillance. However, Schneier noted that this has worked either because phone calls weren’t encrypted at all in the past, or because the encryption protocols the phone companies do use can be easily exploited by third parties.

For instance, in 2004 Vodafone Greece used phone systems that had the phone switches mandated by the U.S. phone interception law CALEA. The switches were turned off by default, but even so, the NSA was able to turn them back on and spy on the Greek prime minister and over 100 other high-ranking dignitaries.

In 2010, China also hacked the backdoor mechanism Google set-up for U.S. law enforcement. In 2015, an unknown group was also able to hack into an NSA backdoor in a random number generator used Juniper’s networking equipment and eavesdrop on Juniper’s enterprise customers.

Schneier also argued that modern systems should be designed not so that they are open to attacks just to satisfy the spy agencies’ surveillance needs, but to be as secure as possible so that everyone is better protected from hackers, criminals, and foreign governments.

Germany, Australia and other countries from the Five Eyes spy agency alliance have also expressed similar wishes to backdoor encryption.

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He covers software news and the issues surrounding privacy and security.