Microdisplay tracks your pupils to adjust brightness, avoid HUD fatigue

Kopin's NeuralDisplay Tech could make it much easier to keep that headset on for long periods of time.

While heads-up displays aren't very common for consumers — Apple's expensive Vision Pro aside — they are already a critical part of the military and medical industries. And, believe it or not, the main problem with HUDs in these mission-critical environments is not cost or even the embarrassment of looking uncool with a big gadget on your head — it's eye fatigue.

When you stare at the microdisplays inside a typical headset, the brightness and contrast remain fixed. Meanwhile, your pupils get larger or smaller based on your physiological and emotional reaction both to the content you are watching and the world around you. For example, if you see something in a movie that makes you emotional and your pupils dilate, all of a sudden the headset will seem annoyingly bright and you might be tempted to flip it off of your head.

Now, imagine a situation where you're a fighter pilot using an HUD to help you in combat, and suddenly you see the an enemy on your radar and your pupil dilates. The headset is suddenly blinding, right when you need its guidance most — and so you pull a Luke Skywalker and take the computer off of your head so you can fight, old-school style. That may sound like a movie script, but in the real world, it's both dangerous and a waste of resources.

Enter Kopin, a company that builds the microdisplays used in many military and medical applications. The corporation has developed and recently announced NeuralDisplay, a technology that builds eye-tracking sensors into the back of a microdisplay and uses custom software to adjust the brightness and contrast of the display in real-time so that it never becomes bright enough to bother you.

Last week, I had a chance to meet with Kopin executives, try some headsets with their existing microdisplays inside and view a video which shows how NeuralDisplay works. That video is embedded below.

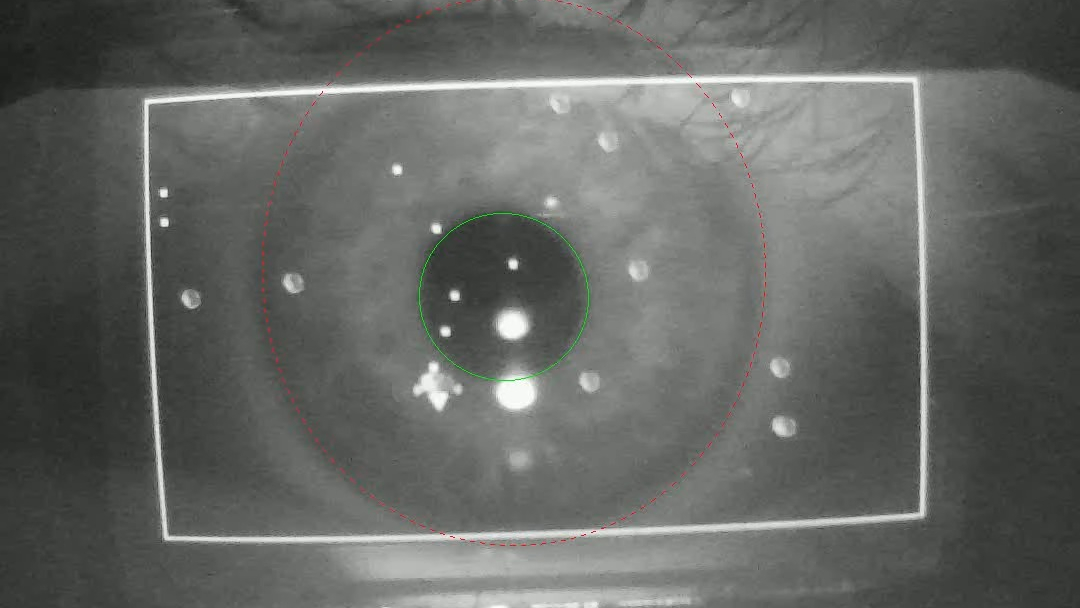

What you see in the video above is a Kopin engineer's eye being tracked as they play a game of Asteroids on a headset. The game itself isn't important; what is noteworthy are the green circle around the pupil and the red dotted circle around the eyeball.

According to Kopin execs I met with, the eye tracking sensors live on the back of the display that the user is looking at — eliminating the need for separate eye-trackers, which use more power and have a longer latency period communicating their findings back to the device. Here, the software looks at the size and rate of change of the pupil and automatically dials the screen brightness and contrast up or down, in less than half of a millisecond (500 microseconds) — so fast that the user won't even detect the change.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Unfortunately, the company doesn't have a NeuralDisplay headset that's ready for demos just yet, but executives promised we would be able to see one in just a few months.

Kopin CEO Michael Murray told us that his impetus for developing NeuralDisplay came when he met with the air force and found out that some pilots were having trouble keeping their headsets on during battle due to changes in perceived brightness. Pilots would see the enemy, have their pupils enlarge and then pop their expensive headsets off (rather than taking time to manually adjust the brightness).

Murray also said that content providers had studied movie viewing on Apple's Vision Pro headset and found that a high percentage abandoned watching movies before finishing them because of the same problem with pupils enlarging and the images seeming brighter.

While NeuralDisplay is most likely to find its way into military and medical applications first, there's no doubt that it could make a huge difference in consumer HUD adoption. By building the eye tracking into the microdisplay, headsets can be thinner, lighter and more power efficient, while also helping consumers avoid HUD fatigue.

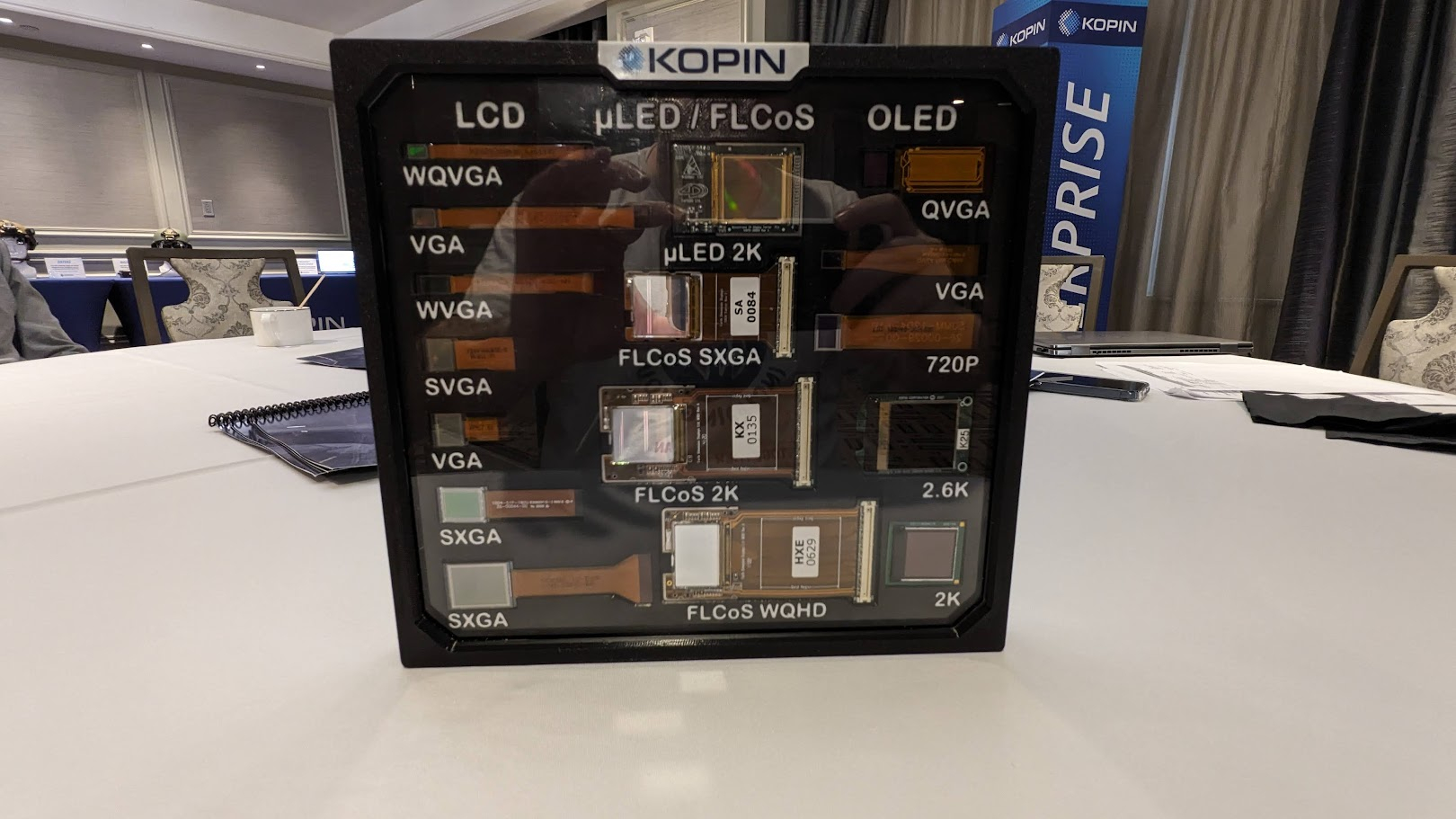

While I was at a Kopin demo suite in New York, I also had the chance to see some of the company's current products in action. The company makes a wide variety of microdisplays with resolutions ranging from VGA all the way up to 2.6K per eye or higher.

While I was there, I tried on a medical headset with 1080p displays that showed a close-up image of a brain surgery. The idea behind the headset is that a surgeon could get a very close look at the brain without craning their neck to look down into the skull cavity. Also, if a robot arm was available, the surgeon could perform the surgery without even being in the same room as the patient.

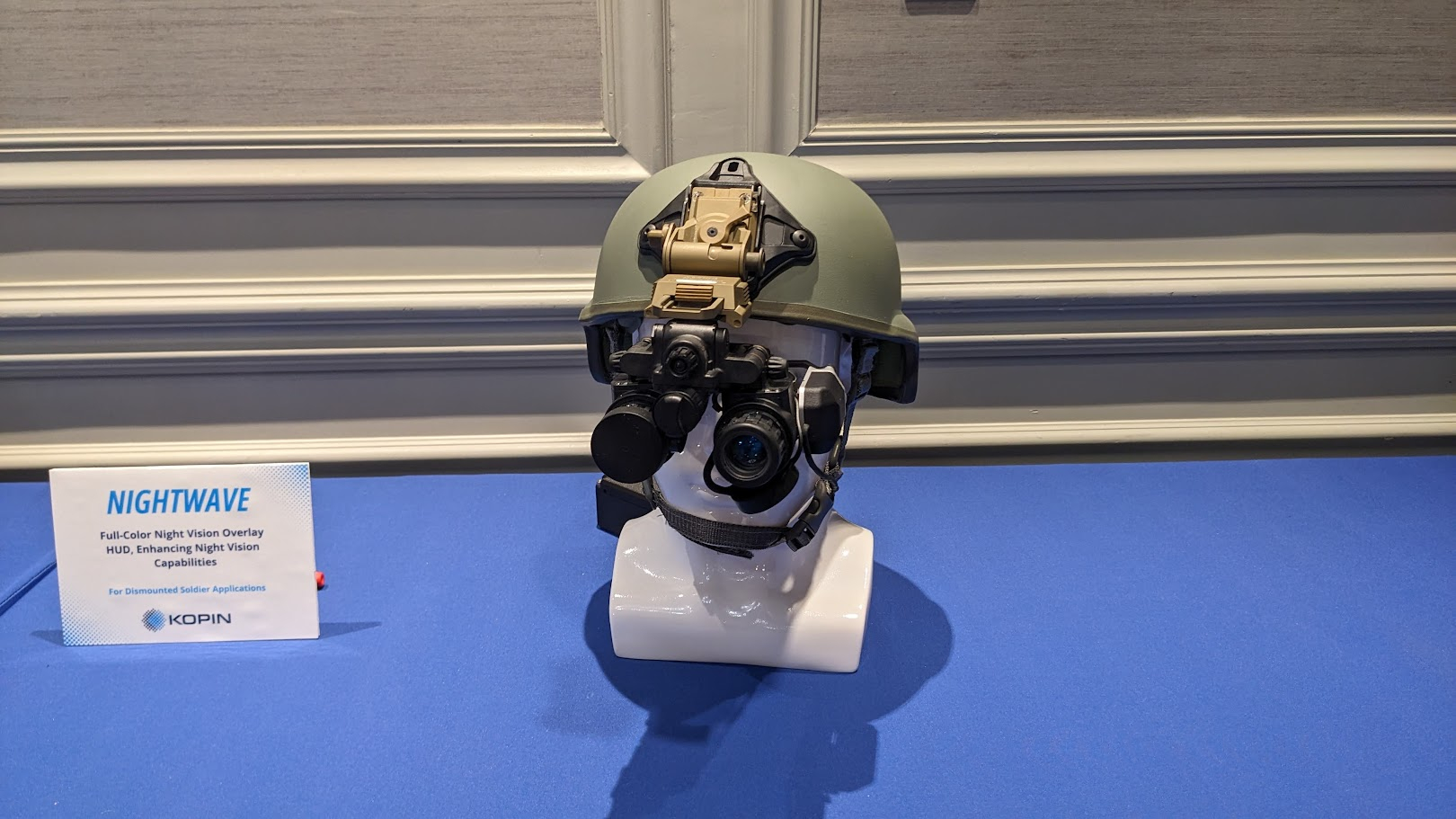

I also got to try on some military HUDs. One of them showed way finder and enemy location information as part of an eye piece, while another inserted that same information on top of night-vision goggles.

The key to all of these screens, Kopin execs said, is that they allow soldiers and medical professionals to get the extra information they need to succeed, without having to take off the headset. Adding NeuralDisplay will undoubtedly allow all users — even consumers, eventually — to wear HUDs for longer periods of time and with fewer annoyances.

Avram Piltch is Managing Editor: Special Projects. When he's not playing with the latest gadgets at work or putting on VR helmets at trade shows, you'll find him rooting his phone, taking apart his PC, or coding plugins. With his technical knowledge and passion for testing, Avram developed many real-world benchmarks, including our laptop battery test.

-

coolitic Seems like a grossly over-engineered solution, when otherwise the problem can be simply solved by adjusting the HUD brightness to match "ambient" light-levels.Reply -

apiltch So it's not about the ambient light. It's about the users' physiological reaction. In other words, you are watching a movie and there's a jump scare in the movie; your retina dilates because of your reaction to that stimuli. That can't be predicted by ambient light and it's not the same for every user.Reply -

edzieba ReplyWhile heads-up displays aren't very common for consumers — Apple's expensive Vision Pro aside

Vision Pro is also not a HUD, it's a Mediated Reality HMD.

When you stare at the microdisplays inside a typical headset

Very few modern headsets use microdisplays, due to the Etendue issue preventing useful FoVs from being achieved, and the limited brightness available - particularly for view-through HUDs.

For example, if you see something in a movie that makes you emotional and your pupils dilate, all of a sudden the headset will seem annoyingly bright and you might be tempted to flip it off of your head.

The real word is also of fixed brightness. Unless 'getting emotional' makes you want to claw your eyes out when walking around your everyday life, this purported effect is imaginary.

There are all sorts of reasons to have pupil-tracking and gaze-tracking (related, but very much not equivalent) in a HMD. Variable brightness based on pupil diameter is not one of them: the only time your pupil will not be directly adapting to the on-screen imagery exactly like it would to any other visual stimuli is when there is a second visual stimulus overwhelming the display - i.e. when using a view-though HUD with an environment of highly varying brightness. In that situation, it is not the display causing visual discomfort that is the problem, but the much brighter external environment washing out the display. That problem has a solution, and it's not a camera system to track pupil size: it's a photodiode facing outward to measure ambient light levels.

ps. existing non-head-mounted and head-mounted HUDs (e.g. the Joint Head Mounted Cuing System) already use adaptive brightness, without any eye-tracking. Ironically, Kopin's products would be worthless for the JHMCS and similar aircraft head-mounted HUDs (like the F-35 HMDS), and they do not use microdispalys. They use 'bird bath' optics with larger panels and delay optics to produce a curved focal surface across a FAR wider field of view than a microdispaly could hope to achieve - that etendue issue again.