World's First Stacked 3D Processor Created

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The University of Rochester has created the first true stacked 3D processor running at 1.4 GHz.

As processors continue to head in the direction of miniaturization, with an ever increasing number of cores, some design engineers believe miniaturization will eventually hit a limit and the only direction left to go will be upwards. One such engineer is Eby Friedman of the University of Rochester, co-creator of a new 3D chip technology, and he believes his new processor is unique to previous 3D chip designs.

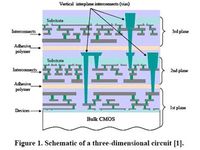

Unlike past 3D chips that were simply stacks of regular processors, this new chip, or "cube" as Friedman calls it, has its layers flush against one another, with millions of tiny holes drilled through the layers to connect them, giving the 3D chip abilities unachievable by single layer processors. The new 3-D processor was designed specifically for optimized vertical processing between layers, much like how traditional processors have been designed for horizontal processing.

Currently the design of the processor Friedman and his students have created clocks in at 1.4 GHz and it is the first 3D chip to ever feature such tasks as synchronicity, power distribution and long-distance signaling. With limits of miniaturization facing the integrated circuit industry, stacking of transistors is believed by some designers to be an eventual direction for processor designs, but such a direction will introduce many new challenges of its own.

Friedman says that one difficulty will be having all the layers interact together as a single system, where accomplishing such harmony in a 3D chip would be much like stacking the traffic systems of the United States, China and India on top of one another. Each traffic system will have its own different set of traffic laws and having to allow drivers at any point move between layers while still simultaneously managing all the other traffic.

A while back we saw IBM looking ahead to 3D chip stacks as well, but the company quickly realized that it would have to overcome a major obstacle -– heat. Conventional cooling methods do not scale well with 3D chip stacks and IBM’s solution to this future problem was designing the chip stacks to allow water to flow between the layers, providing for a scalable cooling solution. Interconnects between the layers would be insulated, protecting them from the water and allowing for the layers to still communicate at high-speeds. Whether or not the new 3D processors that the University of Rochester have designed would be able to integrate similar technologies, has yet to be seen.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

-

harrycat88 Very Interesting...Reply

I've seen micro water pumps on a silicon wafer before. All they would have to do is invent some kind of solution that won't boil, have the micro pumps, pump it between the stacked wafers, and then to the top of the chip trough a heat exchange where the hot solution is cooled trough the heatsink and then back to the pumps and through the wafers again, etc,etc. -

So with this technology we can put more transistors in one piece of silicon but we can't set clock to high because the processor will burn, soReply

it should be good technology for multi core, low voltage, energy saving server processors, for purposes like huge database or web servers under heavy load of thousands threads or for supercomputers. But it wont work for PC desktops until problem with overheating will be solved. -

Heat management is a huge problem here. A microscale, liquid heat exchanger would be very difficult to mass produce...one leaked water molecule would short the circuit system.Reply

This kind of heat transfer technology is at least five to seven years away. Upon viable production, it will turn the CPU cooling world upside down. -

oh my god, what an invention!!!Reply

¬¬ I must have tought of that when I was like 10... what did this guy do? just a pile of processors togheter.

Tell me he solved the problem with heat or created a micro tunneling system to cool down the cube with liquid nitrogen or something like that.

Hey, I invented a 3D processor.

Really? What's it like?

Well, it looks like a pile of processors, actually it's a pile of processors.

Oh... so how they interconnect?

Am... I didn't tought of that yet.

Oh... so how do you cool it down?

Am... I didn't tought of that yet.

Oh... so you just put one processor on top of the other.

No... actually... oh... yeah. -

Ryun That's pretty cool. I actually had this very same idea to make a cube processor but I have neither the background nor am I attending a school that has that background either.Reply

Cooling would be a problem though if the design still resembles a cube after fabrication. -

bounty I'm gonna go ahead and plant my flag in sphere shaped processors to cut down on latency to the corners of your cube. It'll rest on the top of a nitrogen fountain, rotating and beaming out signals.Reply

//then I wake up

I need to patent the multi heatsink design, basicaly we'll go back to slot processors, so we can cool both sides of a 2-4 layer chip, then once they're actually closer to square, you can also put a heat spreader/sink on the top bottom and front, leaving the back for connectivity to the slot on the mobo. -

fazers_on_stun ryunI actually had this very same idea to make a cube processor ...Reply

I think the Borg beat you to it :)