Linux takes 4.76 days to boot on an ancient Intel 4004 CPU — CPU precedes the OS by 20 years

And simple commands can take the best part of a day to execute.

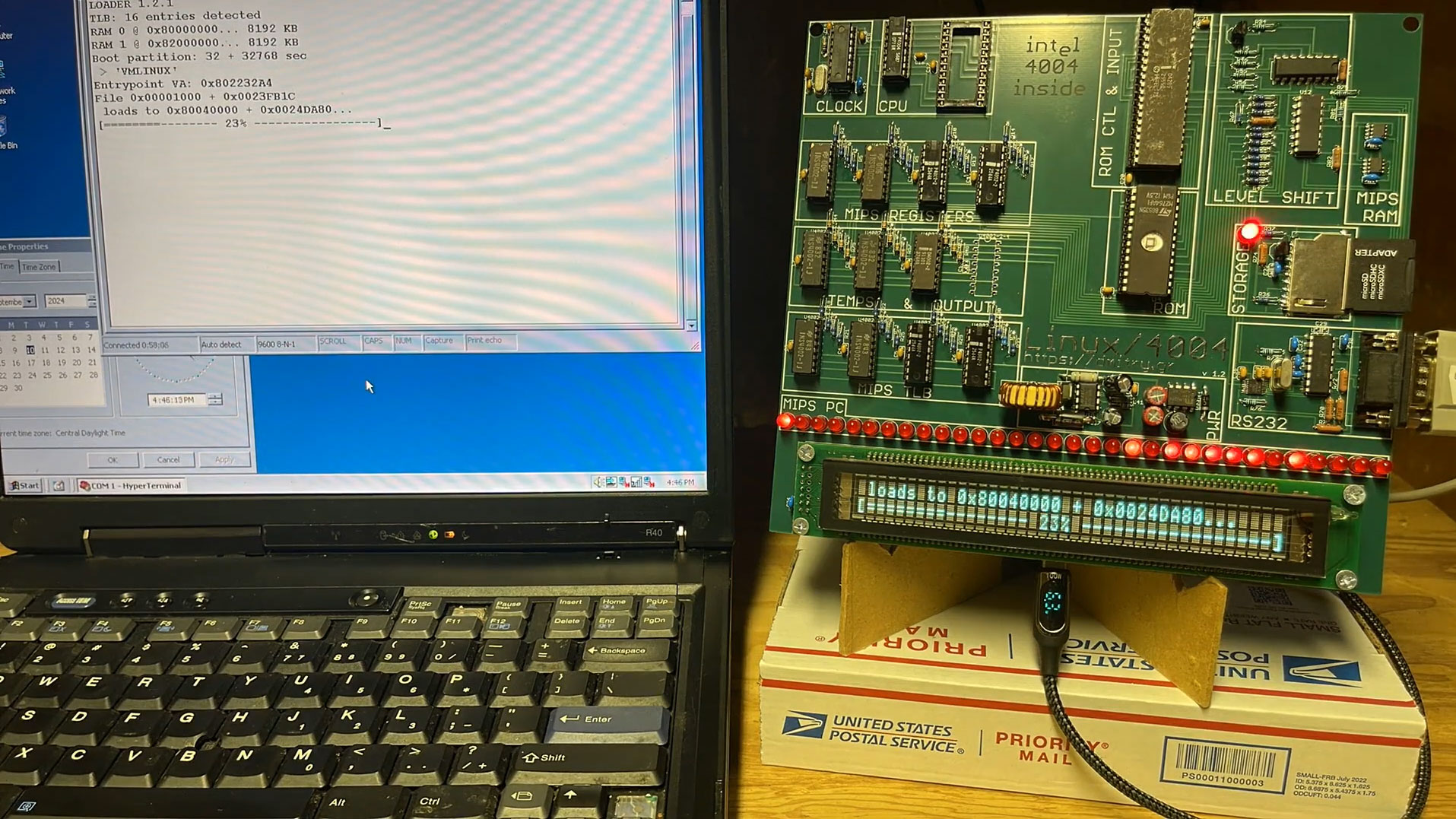

Programmer and hardware enthusiast Dmitry Grinberg has shared a video in which he boots and runs commands on an Intel 4004-powered PC running Linux. The video demonstrates the excruciating time to do anything or execute the most straightforward commands. Booting took 4.76 days, for example, and a simple directory listing didn’t hit the screen until 16 hours after inputting the ‘ls’ command.

Grinberg booted the machine using the Linux prompt. Thankfully, via the magic of video editing, much of the waiting around between commands gets very fast-forward. An unedited version of the video, running at 120x real-time, exists but takes over one hour and 40 minutes for completists.

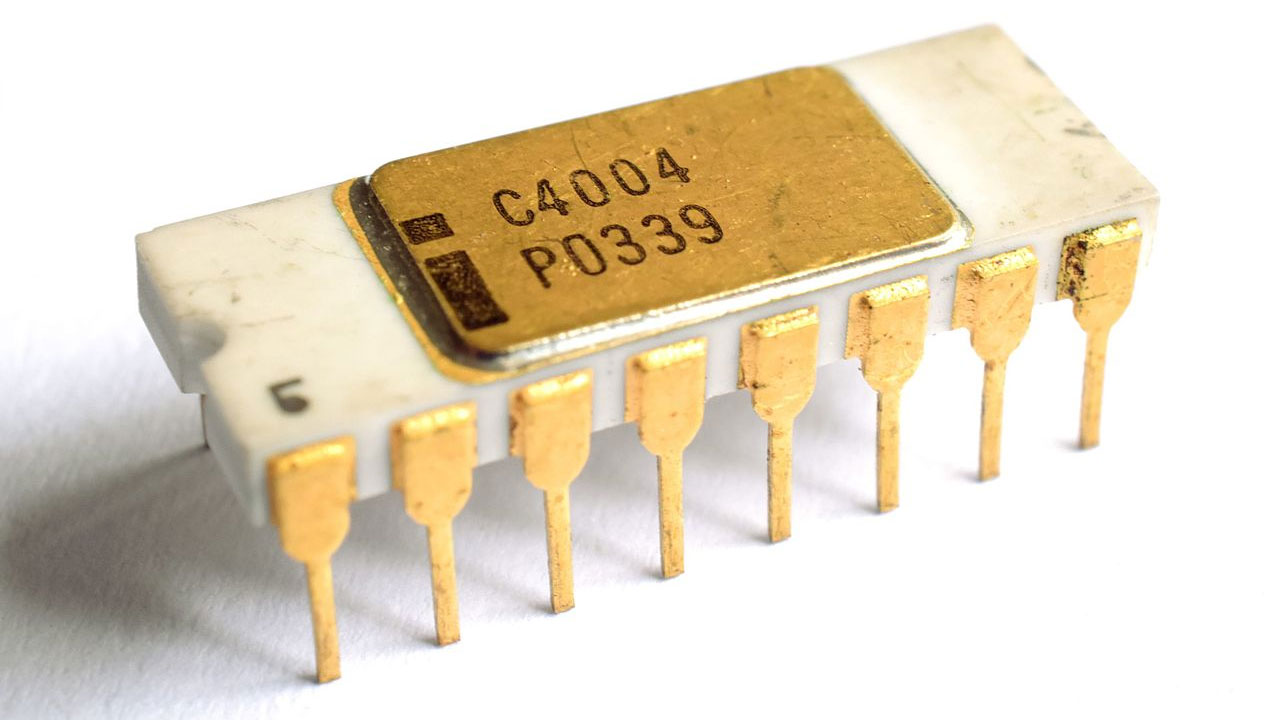

The video begins by pointing out that the world’s first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004 (c.1971), predates the first release of Linux by a fulsome 20 years. This yawning chasm in time, plus the chip’s slowness and lack of modern features, means that Linux never supported it. Therefore, Grinberg needed a little digital wrangling to achieve his feat.

For full details of the project and setup, Grinberg wrote a detailed blog post about ‘Slowly booting full Linux on the Intel 4004 for fun, art, and absolutely no profit.’ In essence, to bridge the hardware/software divide, the enthusiast emulated the more capable MIPS R3000 processor, which boasts the required C compiler support.

Even with these emulation shenanigans, a lot of other background work had to be done, and a large portion of the groundwork for this slow-computing achievement was spent on speed optimizations. Grinberg managed to get the Linux kernel size down to about 2.5MB by removing unnecessary feature support. Thus, he whittled down boot times from around 8.4 days at the start of the optimization process to a wind-in-your-hair 4.76 days.

Moving our attention back to the embedded video, we see it progress from its introductory message to a ‘loading the kernel’ and then a ‘booting the OS’ stage. Eventually, we see the message “Welcome to uMIPS: Feel free to look around slowly” and a blinking prompt on the screen. According to the programmer, we only reached this point nearly five days after power-on.

To begin working in the Linux demo, Grinberg typed in the directory listing command. The system took about 16 hours to list the five or six files in the directory. A similar time was required to type in and execute a command to display the Linux kernel version (Linux uMIPS 4.4...).

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

A glutton for punishment, Grinberg went on to execute commands to display the CPU version—reported to be an R3000 v.2 due to the emulation process going on, as mentioned above. To create some ‘fancy graphics,’ the hacker ran an ASCII Mandelbrot generator. Thankfully, he didn’t add any argument to turn ‘RTX On.’

The video finishes with the system being quizzed regarding its uptime. This command took about 14 hours to execute and output its results to the screen – meaning the system’s reported 22:47:02 uptime was questionable.

Grinberg admits his Linux/4004 project is mainly artistic, but it also demonstrates Linux’s flexibility. He designed the custom 4004 circuit board, with its flashing VFDs and built-in display, for mounting and showcasing on a wall.

If you want to take on this project yourself, the programmer has graciously shared schematics, a priced and linked parts list, a disk image for your SD card, and more. Grinberg is also considering offering the whole thing as a kit or pre-built. If you are interested, drop him a line via the email address on his blog post. However, he warns that a pre-built system might not be cheap, especially if you are looking for a system that includes all the 1970s components.

Mark Tyson is a news editor at Tom's Hardware. He enjoys covering the full breadth of PC tech; from business and semiconductor design to products approaching the edge of reason.

-

bit_user Very misleading article. The 4004 isn't running Linux. You need at least a 386 for that. What it's doing is running an emulator (and for more than just the claimed C compiler support) that's running Linux.Reply

This is akin to other tricks we've seen, where people run some heavy-weight OS on something like the Raspberry Pi Pico, also inside of an emulator. These simple processors lack the sophisticated hardware features needed to run a complex OS. The only way you can do it is by having it emulate a much more capable CPU.

That obviously comes at the expense of a lot of additional performance, which is how we end up with the astonishingly bad execution times quoted in this article.

I'm sure they also had to use some sort of hack for giving it access to enough memory that it could run an OS like Linux. That's going to come at an additional performance hit, since it's likely making an I/O request per each memory read/write, each of which must be broken into multiple steps for the entire 32-bit address to be written out. Keep in mind that a simple, ancient CPU like the 4004 had no caches, either.

No, not that flexible!The article said:it also demonstrates Linux’s flexibility. -

tony-w I'm amazed that someone could put enough effort into all the emulation and memory paging required to make a 4 bit Intel 4004 do this. The chip was initially developed to run a calculator. It can only directly address 1,280 4 bit RAM locations and 32,768 bits of ROM equivalent to 4,096 bytes. Just about all the code running directly in the CPU address space must have been dedicated to paging in and out memory.Reply

It does make me wonder - WHY -

bit_user Reply

Yeah, the real heroes of this piece are the MIPS emulator that's small enough to fit on the 4004, and yet complete enough to boot Linux. Then, the extended memory hack that enabled enough RAM to be connected.tony-w said:I'm amazed that someone could put enough effort into all the emulation and memory paging required to make a 4 bit Intel 4004 do this.

Thanks for the specs. I was too lazy to look them up, myself. I'd guessed it must be something tiny. So, 640 bytes of RAM? If you're used to thinking in such small quantities, I can see why 640 kB might indeed seem like enough for everybody!tony-w said:The chip was initially developed to run a calculator. It can only directly address 1,280 4 bit RAM locations and 32,768 bits of ROM equivalent to 4,096 bytes.

; )

It had no paging mechanism, as far is know. That doesn't mean the emulator couldn't have introduced its own form of soft paging, but the hardware wouldn't be helping you out with that.tony-w said:Just about all the code running directly in the CPU address space must have been dedicated to paging in and out memory.

Art?tony-w said:It does make me wonder - WHY

It does give me some hope that post-apocalyptic peoples could one day boot early Linux distros they find amidst the rubble, even if the only functional computers they have at that time are 1970's era machines, or equivalent. To be honest, I don't really know how a Linux image would even survive in a format they could read. CD-ROM was 1980's technology, but I'm not sure how long even pressed CDs could last. -

newtechldtech intel ... When I was studying at TUM in Germany , back in the day , we never had a single intel chip at the computer lab , ALL were SUN stations running Unix which lead to Linux ... Intel was Nothing back then ... how things changed ...Reply -

bit_user Reply

Well, the 386 built on the foundations laid in the 286 to provide support for memory protection and virtual memory that server & workstation operating systems demanded. The 486 was first to integrate the FPU and the Pentium made it actually somewhat competitive with competing RISC CPUs, eroding the last major advantage they had. Pentiums were also the first to support multi-CPU cache coherency, enabling up to quad-CPU machines.newtechldtech said:intel ... When I was studying at TUM in Germany , back in the day , we never had a single intel chip at the computer lab , ALL were SUN stations running Unix which lead to Linux ... Intel was Nothing back then ... how things changed ...

Even so, up to the late 90's, many university CS departments looked down on PCs and preferred to keep using Sun and SGI workstations. Probably the beginning of the end was when SGI released its first x86 workstation, back in '98 or '99.

I think Microsoft also helped turn the tide by donating PCs (running Windows, of course) to some bellwether colleges and universities. They were also influential by means of fellowships. I used to work with a guy who interned at Microsoft Research for 3 summers, while he was in grad school. I don't know how he felt about Microsoft before that (didn't know him back then), but it he would certainly sing their praises afterwards. -

tony-w Back in the late 70's when I was responsible for developing my first data communications product I used a Motorola 6809 processor. I remember how great it was to have the luxury of 8K bytes of UV erasable EPROM and 8K bytes of static RAM to play with when compared to "earlier" processors like the 4004 or 8008. (The 6809 could address more RAM & ROM but memory was so expensive back then we could not afford to put more in our products.) It was amazing what you could achieve with so little RAM and ROM although there was a lot of effort put into looking at how many clock cycles each instruction took to get the best overall performance.Reply -

bit_user Reply

In modern communications equipment and certain embedded applications, there's still a lot of cycle-counting. Back in the early 2000's, I worked on a layer 2 networking product that had to maintain line rate. At the fastest supported speeds, we had just a couple dozen cycles to handle each piece of data coming in. There were DMA engines that handled the actual data movement, but the firmware had to decide what to do with it.tony-w said:It was amazing what you could achieve with so little RAM and ROM although there was a lot of effort put into looking at how many clock cycles each instruction took to get the best overall performance.

When you're running that close to the limit, there's no headroom for high-level languages or a proper OS of any sort. It was all assembly language. -

ottonis Reply

Thanks a lot for this very interesting and useful explanation! Running an emulation of a complex CPU that could run a modern OS is a task that most very old CPUs will only be able to run in extreme super-slow mode.bit_user said:Very misleading article. The 4004 isn't running Linux. You need at least a 386 for that. What it's doing is running an emulator (and for more than just the claimed C compiler support) that's running Linux.

This is akin to other tricks we've seen, where people run some heavy-weight OS on something like the Raspberry Pi Pico, also inside of an emulator. These simple processors lack the sophisticated hardware features needed to run a complex OS. The only way you can do it is by having it emulate a much more capable CPU.

That obviously comes at the expense of a lot of additional performance, which is how we end up with the astonishingly bad execution times quoted in this article.

I'm sure they also had to use some sort of hack for giving it access to enough memory that it could run an OS like Linux. That's going to come at an additional performance hit, since it's likely making an I/O request per each memory read/write, each of which must be broken into multiple steps for the entire 32-bit address to be written out. Keep in mind that a simple, ancient CPU like the 4004 had no caches, either.

No, not that flexible! -

fidelcatsro Wow! 4004 chip from 1971, just the chip i need to get my home made nuclear fusion reactor working!Reply -

t3t4 I believe this falls under the category of: Just because you can doesn't mean you should.Reply