Preparing Smithfield for mass production

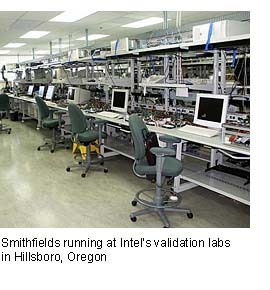

Hillsboro (OR) - Tom's Hardware Guide got a chance to peek into Intel's validation labs - where pre-production processors are sent through a painful parcours with stress, application and overclocking tests to prepare processor designs - including the manufacturer's first dual-core chip - for mass production.

Consumers want to be certain that the product they buy is reliable, no matter if it has been in production for some time or if it is brand new. That is not only the case for example for the automobile industry where prototypes of new cars are sent through extreme terrains such as California's Death Valley or arctic environments in Scandinavia. Similarly, processor manufacturers have developed test procedures that aim to reveal design errors and the limits of a chip.

Intel validation process involves several processes such as testing, probing and error correction and spans across the globe with locations in Malaysia, Ireland and the United States. According to Kea Grilley, ecosystem co-validation manager at Intel, more than 3500 people at Intel are involved in chip validation, up from about 200 in 1995.

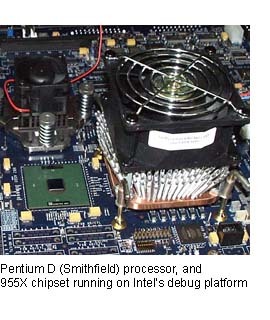

According to Grilley, the validation platforms, each carrying a $20,000 price tag, are proprietary designs for Intel and include specially designed performance heatsinks to enable a narrow design of the components on the board. The company also runs tests on designs that consumers may see in commercial products, she said. Overclocking is a standard part of the validation: "You bet we overclock," Grilley said. Of course, Intel does not recommend any overclocking and does not give any guarantee, but Grilley said she "has seen Smithfields reaching 4 GHz" before becoming unstable, while others already passed out at 3.3 GHz.

The huge investment Intel puts into validation - Grilley declined to mention specific numbers - has a reason: The cost of errors in products that are shipped in millions globally can be much higher, as the company learned for example back in 1995. The now famous "FDIV error" was based on a division error in the first Pentium processor causing not only the creation of a task force and the involvement of executive staff including Andy Grove and Craig Barrett, but also a massive recall. While Intel never publicly revealed the actual cost of the most prominent product error in the manufacturer's history, the company said in 1995 it had set aside $420 million to cover related costs.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Wolfgang Gruener is an experienced professional in digital strategy and content, specializing in web strategy, content architecture, user experience, and applying AI in content operations within the insurtech industry. His previous roles include Director, Digital Strategy and Content Experience at American Eagle, Managing Editor at TG Daily, and contributing to publications like Tom's Guide and Tom's Hardware.