20 Companies And Products We Remember Fondly

Take a trip down memory lane with us as we recall some of the hardware products and software applications that got us hot and bothered about technology when we were younger. From MS-DOS to 3dfx, our list of favorites is fairly diverse.

3dfx

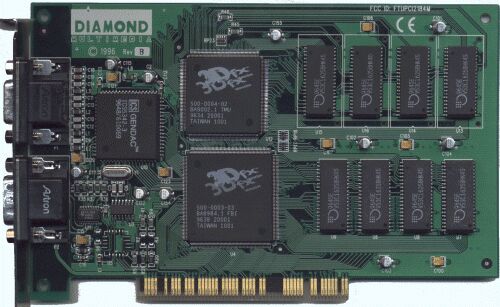

There's no question that GPU manufacturer 3dfx helped change the face of PC gaming, and indeed the entire gaming industry. It started with the Voodoo Graphics chip back in 1996, supplied in various arcade gaming machines during a time when arcades still showcased the latest and greatest technology (although consoles eventually killed them off).

But when EDO DRAM prices dropped by the end of the year, 3dfx went into the PC business and brought forth its now-classic Voodoo Graphics PCI card. At the same time, id Software released its latest FPS game, Quake, ditching the pixel-based graphics engine used with previous games, and turned to vector-based polygons to create a more compelling experience. Taking advantage of 3dfx's miniport OpenGL driver, the revamped Quake (GLQuake) suddenly took PC gaming into a new era of graphics, providing smooth surfaces, gorgeous textures and lighting, and screaming-fast frame rates.

In 1998 3dfx took the GPU industry a step further and introduced Scan-Line Interleave, the ability to install two Voodoo2 boards and use them together as one processing power house. However over the next few years, the company saw a shift in strategy and an overall decline, leading to a filing for bankruptcy in 2000 and Nvidia's subsequent acquisition.

This one's for you, Billy.

Nvidia's Riva TNT

Once 3dfx shipped its Voodoo2 graphics card, rival GPU company Nvidia (which purchased 3dfx years later) released the RIVA TNT, successor to its RIVA 128. The GPU's name was an acronym for Real-time Interactive Video and Animation accelerator. TNT was short for TwiN Texel, its ability to work on two texels at once, thanks to a second pixel pipeline.

Although the TNT offered support for 32-bit color and 1024x1024 textures, the Voodoo2 (which offered 16-bit color) had it beat using a special MiniGL driver created specifically for 3dfx cards. The Voodoo2's native SLI support, linking two Voodoo2 boards together, also proved to be quite competitive.

But the TNT demonstrated that Nvidia was a serious contender in the GPU market. The card's launch kick-started Nvidia's aggressive stance to stay on top of device drivers and release updated versions on a regular basis, beginning with the release of the first branded driver, Detonator.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Nvidia was also the first to release a budget-version of its flagship GPU. Called Vanta, this lower-priced TNT had a reduced clock speed, along with half the memory data bus width and memory size. Vanta was a way for Nvidia to still sell TNT GPUs that wouldn't reach higher target clock speeds.

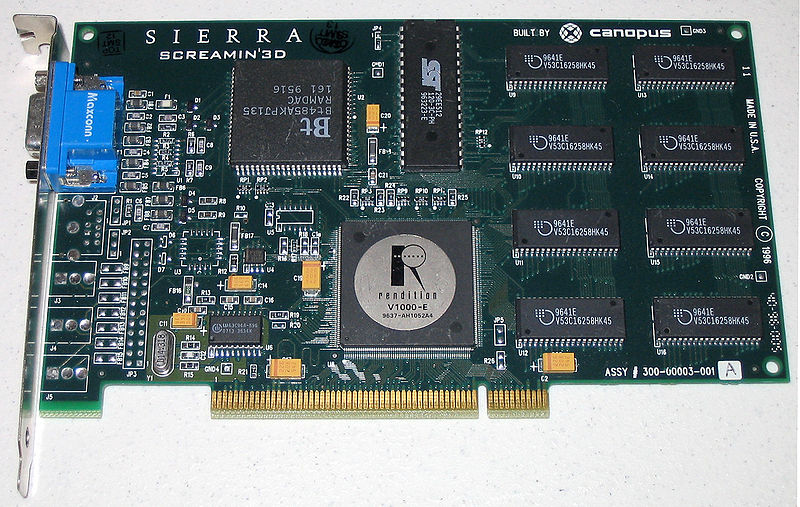

Rendition's Sierra Screamin 3D

Although the company basically only produced two GPUs in the mid- to late-90s, Rendition was a major competitor to 3dfx and Nvidia in its day. Supposedly, Rendition worked directly with id Software's John Carmack to make a hardware-accelerated version of Quake (called vQuake). However, 3dfx also offered its own API-laden version that seemed to have Carmack's signature as well.

The biggest selling point of the company's first entry, the Vérité V1000, was that it offered both 2D and 3D support. 3dfx didn't offer a combo card until later on with the Voodoo 3. Digging the 2D/3D combo, three companies jumped onboard the Vérité V1000 bandwagon: Creative Labs (3D Blaster PCI), Sierra (Screamin' 3D), and Canopus (Total 3D).

Eventually, Carmack set the record straight with regard to who ruled the GPU market, saying that Rendition's 3D accelerator was id's "clear favorite," despite 3dfx's popularity. Indeed, the visuals were simply awesome when compared against 3dfx's GLQuake. Unfortunately, neither company survived the turn of the century.

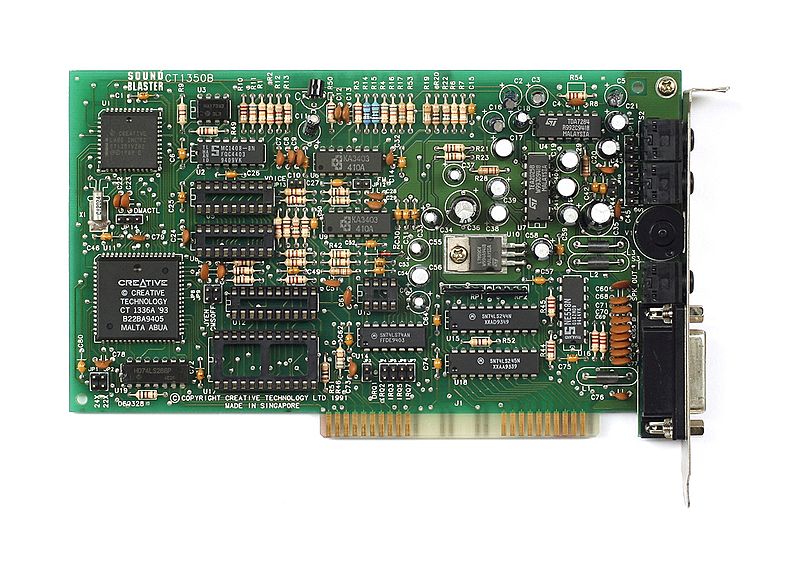

The Early Days Of Creative's Sound Blaster

Starting out as a simple computer repair shop, Creative became a standard in PC audio up until Windows 95 and less expensive integrated sound solutions hit the market. Most old-school PC gamers remember the SET BLASTER environment for DOS listed in the AUTOEXEC.BAT file, manually presetting the port address, interrupt, DMA channel, the type of card, MIDI port, and the "high" DMA channel before loading up any PC game or program that required the use of a discrete sound card.

Creative took the market away from AdLib to the point of bankruptcy back in 1992. By then, Creative had already overhauled its popular Sound Blaster line with the Sound Blaster Pro, offering faster digital sampling rates. The card was also the first to incorporate a built-in CD-ROM interface. But when the Sound Blaster AWE32 had reached the market two years later, the company revamped its MIDI synthesizer and split the card into two distinct audio sections.

Today, high-definition audio is commonplace. But where would we be without Creative? The company set the standard decades ago, and showed the general consumer and hardcore gamer that PCs were capable of generating more than beeps and boops from chassis-mounted PC speakers. As time passed, the aural experience evolved from a stereo affair to surround sound. Despite some of the annoyances brought on by the new technology (like shoddy software drivers), the early days of the Sound Blaster are missed.

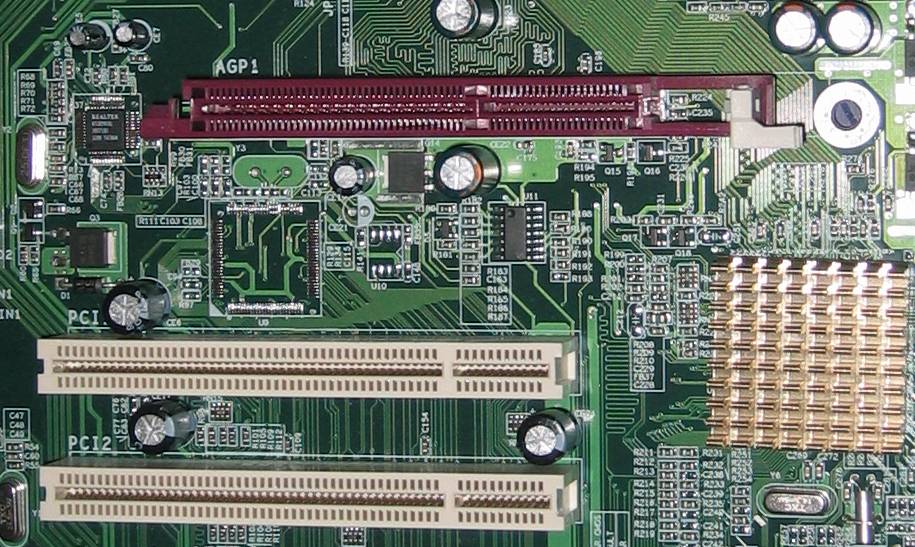

The Accelerated Graphics Port

Before we had PCI Express, we had the Accelerated Graphics Port (AGP), which represented a step up from the bottlenecked PCI bus. The conception of this port was due to the limitations of PCI and the ever-increasing burdens of heavy graphics processing.

The advantage over the older technology was that AGP cards had direct access to the processor, rather than sharing resources with an entire PCI bus. AGP cards could also read textures loaded in the system RAM directly. PCI cards copied the textures from the RAM and placed them into their local framebuffers first, slowing down the rendering process.

AGP's reign didn't last long. PCI Express finally came along in 2004. Until then, the AGP slot offered a rate of 266 MB/s when it was first introduced. Some of the early graphics processors that supported AGP included the 3dfx Voodoo Banshee (even though it ran in PCI mode), Nvidia's RIVA 128, Rendition's Vérité V2200, and the ATI Rage-series.

The Math Coprocessor

Gamers who spent years playing Doom and its derivatives on a 486 computer were probably in shock when id Software's Quake wouldn't run on systems with NexGen and 486sx chips. Specifically, the pre-release "demo," called qtest1, was released in early 1996 to see how the game would run on various systems. id said that it was possible to run the test using an emulator (Q87 or the WMEMU387 in DJGPP). However, the frames would run extremely slowly. Evidently, the game needed floating-point math support, and a math coprocessor was the ticket.

In this case, the chip was used to offload the extra math calculations the 486 couldn't handle on its own. Of course, meatier processors and GPUs came along to help out with the rendering, however qtest1 and its math coprocessor requirement were two signs that PC gaming was about to take on a more serious tone on the hardware front.

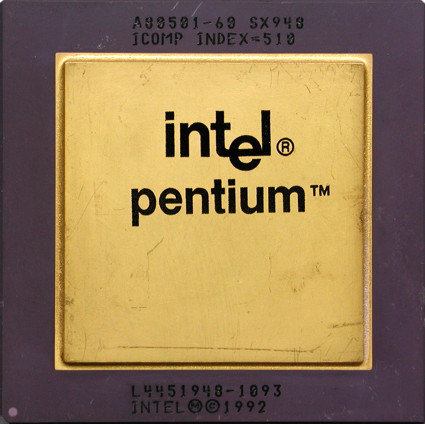

The Original Pentium CPU

There's no question that the Intel "P5" Pentium processor brought a whole new experience to the personal computer. A huge step up from Intel's 80486, the new CPU featured two pipelines that allowed for more than one instruction per clock cycle, a faster floating point unit, and more. By today's standards, the CPU was anemic, clocking in at 60 or 66 MHz.

Eventually the Pentium broke into 100 MHz territory with the P54C. Three years later, the Pentium MMX (P55C) hit the market using the same basic microarchitecture as the older Pentium, but came packed with even larger caches, MMX instructions, and a few other additions. This processor was promoted to improve the performance of multimedia tasks, thanks to the additional 57 MMX instructions.

Cyrix Corporation

For a brief moment, the Cyrix Corporation, with its popular 6x86 (M1) line of processors, was a big contender in the CPU race of the late 1990s. Typically, the chips were named to reflect their slightly less powerful Intel Pentium counterparts. They also fit within Intel-designed sockets. The vendor had a following of computer shops and gamers, more than likely because it was an option besides Intel and AMD. Cyrix originally tried to charge a premium for the 6x86 CPUs. However the popularity of first-person shooters and other 3D games at the time eventually forced the company to lower its prices.

Despite its seemingly faster performance, the 6x86 was inferior with regard to its math coprocessor. Because it lacked instruction pipelining, 3D games like Quake choked in performance.

Cyrix merged with National Semiconductor in 1997, and the last processor bearing the Cyrix brand was the MII-433GP. Clocked at 300 MHz, the chip performed better than AMD's K6-2 300 on floating-point unit calculations, however it couldn't contend against processors that actually ran at 433 MHz. After its release and the negative feedback from "unfair comparisons," the merger dissolved with National Semiconductor leaving the CPU market and VIA Technology purchasing the remaining portions of Cyrix.

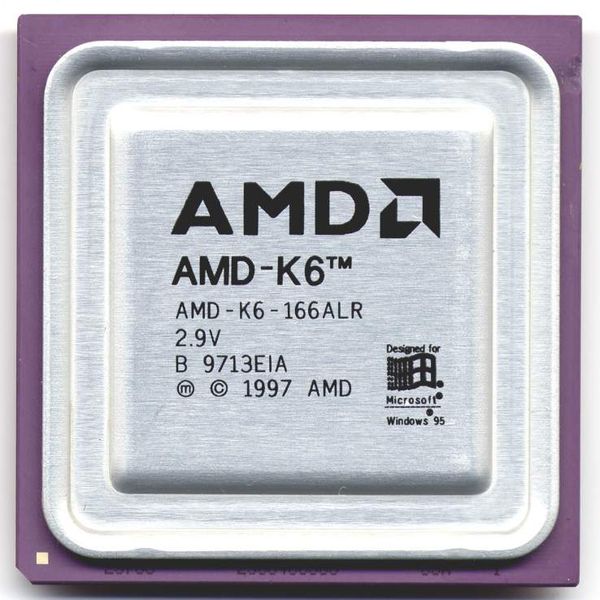

AMD K6

Like the CPUs manufactured by Cyrix, AMD's K6 processor was also designed to fit within Intel-designed Socket 7-based motherboards. But unlike the Cyrix processor of the time, AMD's K6 was co-developed by the original lead designer of the Intel P5 architecture, and was based on the Nx686 microprocessor designed by AMD's just-acquired NexGen. The CPU itself was flagged to be AMD's return to the Intel-compatible processor market, taking on Intel's Pentium II without breaking a sweat.

When the processor launched in 1997, it was offered with two clock speed variations: 166 MHz and 200 MHz. The company later released a third version running at 233 MHz, followed by a 266 MHz model in Q2 '98. A final version clocked in at 300 MHz, and was launched May 1998. All versions featured MMX instructions, a floating point unit, and a feedback dynamic instruction reordering mechanism.

The K6-2, a variation of the original K6, featured AMD's 3DNow, a set of floating point-based Single Instruction Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions that were added to the base x86 instruction set. This allowed for simple vector processing, thus improving the performance of 3D games and other graphics-intensive software.

Gaming Shareware

To be honest, shareware is a retired business model that really needs to make a return. Oh sure, you'll find forms of shareware and freeware still available on the Internet. However there was something special about gaming shareware that brought popular PC franchises to the masses. Titles like Doom, Wolfenstein, Heretic, Rise of the Triad, and even Duke Nukem 3D all used the shareware model, providing gamers one of many episodes that, in itself, contained numerous levels.

Looking back, the shareware model probably wouldn't work with games today, as production costs have soared through the roof compared to the early '90s. Still, we have fond memories of the old-school shareware model: download a game, install it, and play it over and over again without spending a dime.

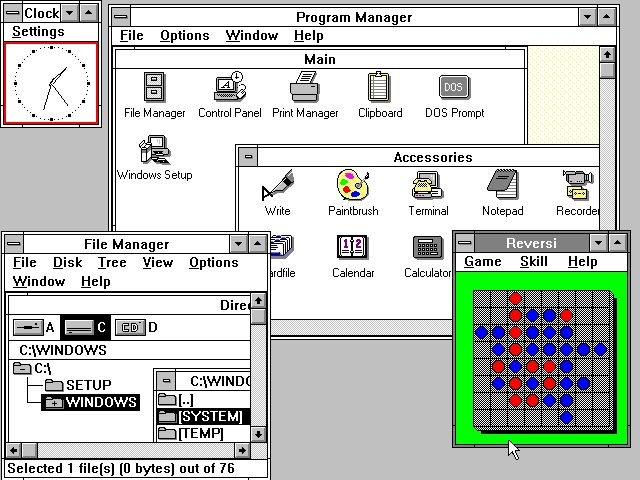

Microsoft Windows 3.0

Windows 3.0 and Windows 3.1 seemed to mark a giant leap in the evolution of the PC, going mainstream and offering users a visually-pleasant environment in which to work, listen to music, and even play games. Who didn't sit in front of the monitor for hours playing Solitaire, when a perfectly good deck of cards sat untouched in a drawer somewhere? This version even looked and performed better than the previously-boring Windows 2.1x, offering a revamped user interface and better memory management.

Strangely enough, there was something about 3.0 that was barbaric and magical at the same time--barbaric in that we still needed to boot with config.sys and autoexec.bat, barbaric in that it felt more like a turbo-charged MS-DOS program rather than a new OS, but simply magical because it was a far cry from...

Kevin Parrish has over a decade of experience as a writer, editor, and product tester. His work focused on computer hardware, networking equipment, smartphones, tablets, gaming consoles, and other internet-connected devices. His work has appeared in Tom's Hardware, Tom's Guide, Maximum PC, Digital Trends, Android Authority, How-To Geek, Lifewire, and others.

-

alberthynek wait the k6 300mhz launched in 1998, not 2008.Reply

"A final version clocked in at 300 MHz, and was launched May 2008"

-

Number 18 - The floppy disk.Reply

You haven't lived till you've sat through numerous installs of MS Office 4.3 which came on over 40 3.5" floppys. -

frye It's too bad I'm too young to have appreciate or remember any of these things, except for the floppy. Can't wait to see this list 15 years from now! (Whad'ya mean you only had a 4-core CPU!?!?!)Reply

-

mitch074 Some errors in that retrospecive...Reply

- although mounted on an AGP card, the Banshee processor still worked in PCI mode, not enjoying the memory access granted by AGP (but using the bandwidth); there was hardly a difference in performance between the PCI and AGP versions.

- Quake never used Glide; 3dfx wrote a miniport OpenGL driver for the Voodoo cards, and Quake used that.

- the OPL3 was an advanced frequency modulator chip with stereo capabilities, and was coupled with the digital sound processor (the Sound Blaster Pro came with an OPL2 chip, the Sound BLaster Pro 2 had an OPL3, but both had the same DSP; the Sound BLaster 16 also had an OPL3 chip). -

carlhenry i remember loading up dos and giving up windows 95 just to play a ton of apogee games. i forgot some but i still remember playing raptor. fighter jet ftw!Reply

oh, the wolfenstein screeny is very nostalgic! good 'ol days!

i still remember 1995 that my pentium 166mhz was $1.2k! now i'm stuck with a ~$500 rig. -

jhansonxi Windows 3 was horrible. UAE errors all over the place. It wasn't really usable until WfW 3.11 was released.Reply

Don't forget about VESA Local Bus and the early battle with Intel and PCI v1.0 (which was garbage then).

I also liked STB's cards before 3dfx bought them out. I loved my Powergraph Ergo with its S3 chip. But that was a long time ago and now I wouldn't use S3 chrome garbage in a print server.

A lot of motherboard chipset vendors used to compete on high-performance desktop boards but we're down to three now. When was the last time you saw a high-end MB with a Via or ALi chipset?

Same goes for a lot of motherboard vendors. I really liked my old AOpen board. They had a lot of nifty designs. Remember the one with the tube amplifier?

Some good system builders disappeared when margins shrunk down to nothing, like Northgate. Of course some we're better off without like Packard Bell. -

stridervm I know and used all of these devices except the commodore tape drive. Does that make me old? :(Reply