AMD Radeon FreeSync 2: HDR And Low Latency

AMD crammed a lot of FreeSync love into 2015, starting with a proliferation of compatible displays and ending with the introduction of low-frame rate compensation (LFC). That latter capability addressed one of G-Sync’s main advantages. Specifically, any time the frame rate of your favorite game fell below the minimum variable refresh of your FreeSync monitor, the technology stopped working, and you ended up with motion judder or tearing.

FreeSync Evolves

LFC was a much-needed addition to FreeSync, and because AMD implemented it through the Crimson driver, many monitors supported LFC right away. Others did not, though. Enabling LFC required a maximum refresh rate greater than or equal to 2.5x the minimum. So, panels with a variable refresh range between 40-60Hz, or 48-75Hz, or 55-75Hz couldn’t benefit from it.

Those early growing pains and a later lack of feature/range consistency from one monitor to the next meant many enthusiasts continued thinking of FreeSync as the more affordable, but less refined, alternative to G-Sync.

Today, AMD enjoys a sizeable lead over Nvidia when it comes to variety—the company claims that >6x as many models support FreeSync—and the latest implementations really are quite good. Improvements continue rolling in, too. FreeSync is now supported over HDMI on certain monitors, and the feature was recently made to work in full-screen borderless windowed mode.

But AMD knows it has a mindshare battle to fight against a competitor notorious for tightly controlled, proprietary IP, so it’s shedding some of those open standard ideals in a bid to attract the gamers willing to pay top dollar for an assuredly positive experience.

Enter FreeSync 2.

One Step Closer to HDR

We had a long chat with AMD about HDR back in 2015, and the company shared its vision for high-dynamic range rendering. Although it didn’t seem like much happened to further this cause on the PC in 2016, Sony’s PlayStation 4 Pro and Microsoft’s Xbox One S—both powered by AMD graphics—added support via HDR10. We also started seeing TVs capable of increased color range and brightness compared to sRGB. Even games began rolling out to validate those extra investments in marginally-faster consoles and expensive displays.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

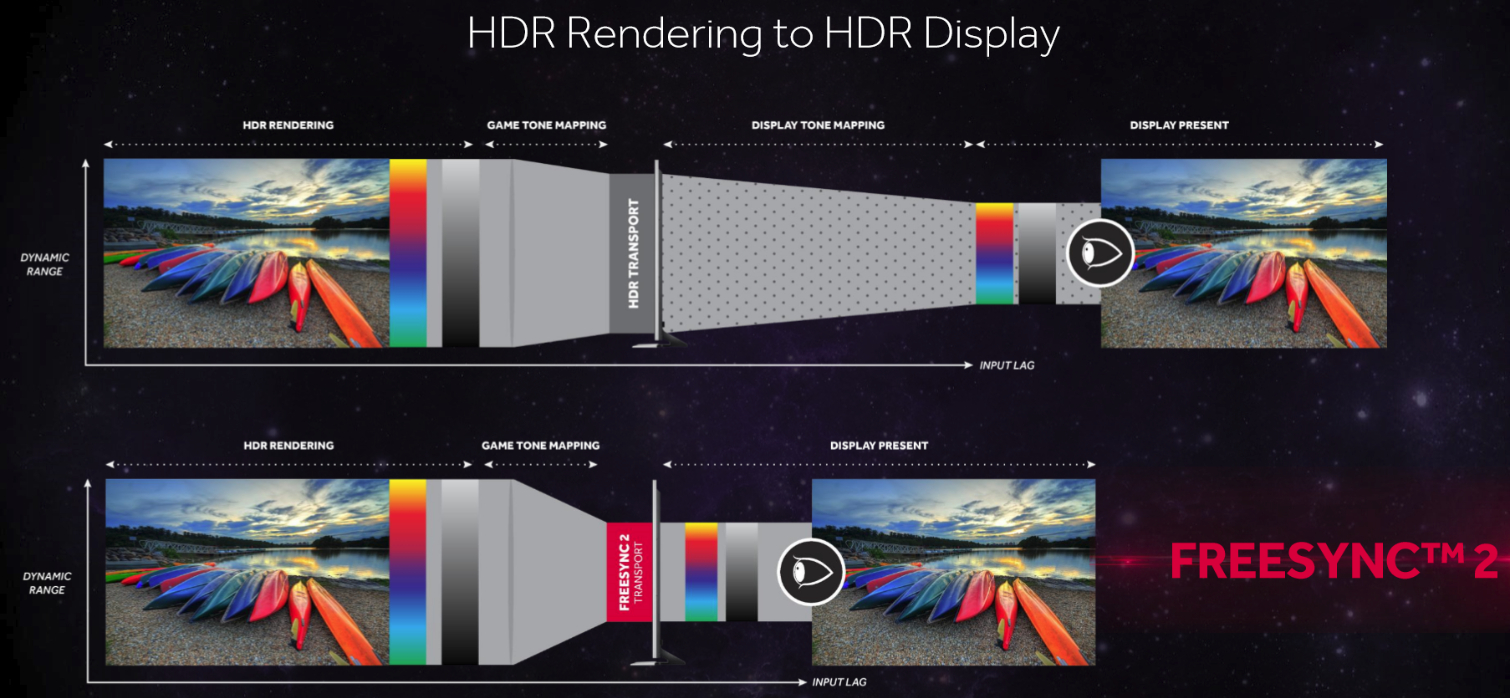

The headline feature of Radeon FreeSync 2 promises to get this same goodness onto the PC in 2017, and the result should be better than anything console gamers are getting today. FreeSync 2’s significance is summarized in a single slide:

What you’re seeing is the elimination of the tone mapping a monitor must go through to present an HDR-rendered image. FreeSync 2 enables this by feeding the game engine (all the way on the left side of the diagram) specific information about the display you’re using. In return, you get the best possible image quality that the monitor is capable of, because the game tone-maps to the screen’s native characteristics. There’s also a notable reduction in input lag, as illustrated in AMD’s slide.

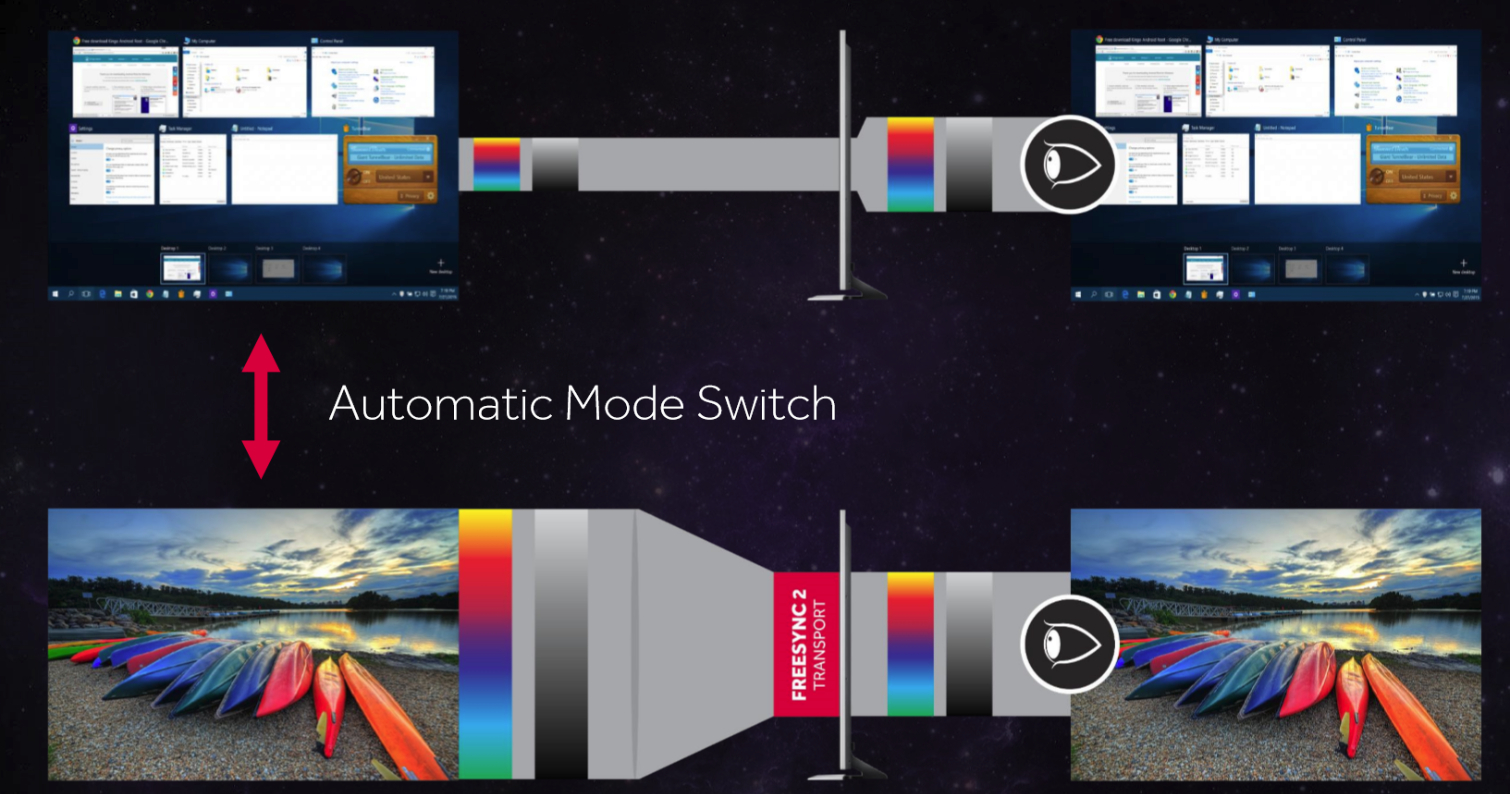

Of course, you wouldn’t want to use non-managed software in the same mode. So AMD adds an automatic switch to take you into HDR and then return to however your monitor was previously configured.

The question of why not simply use the HDR10 or Dolby Vision transport spaces is already answered, then—they’d require another tone mapping step. David Glen, senior fellow architect at AMD, said that HDR10 and Dolby Vision were designed for 10 or more years of growth. Therefore, even the best HDR displays available today fall well short of what those transport spaces allow. That’s why the display normally has to tone map again, adding the extra input lag FreeSync 2 looks to squeeze out.

Sounds like a lot of work, right? Every FreeSync 2-compatible monitor needs to be characterized, to start. Then, on the software side, games and video players must be enabled through an API provided by AMD. There’s a lot of coordination that needs to happen between game developers, AMD, and display vendors, so it remains to be seen how enthusiastically AMD’s partners embrace FreeSync 2, particularly because the technology is going to be proprietary for now.

Fortunately, AMD is giving us some assurances about what FreeSync 2 is going to mean. To begin, branded displays must deliver more than 2x the perceivable brightness and color volume of sRGB. While seemingly an arbitrary benchmark to set, remember that AMD wants this technology to launch in 2017. It has to work within the bounds of what will be available, and AMD’s Glen said that satisfying a 2x requirement will already require the very best monitors you’ll see this year.

FreeSync 2 certification is also going to require low latency. Glen stopped short of giving us numbers, but he did say more than a few milliseconds of input lag would be unacceptable. Finally, low frame rate compensation is a mandatory part of FreeSync 2, suggesting that we’ll see wide VRR ranges from those displays.

AMD expects FreeSync and FreeSync 2 to coexist, so you’ll continue seeing new FreeSync-capable displays even after FreeSync 2-certified models start rolling out. Any AMD graphics card that supports FreeSync will support FreeSync 2, as well.

-

TechyInAZ Reply19097716 said:If you are on Monitor with 144+ Hz FreeSync and GSync are useless.

No not really. Just because you have a high refresh rate doesn't mean their useless.

If you have hardware that can't maintain 144fps all the time, then those technologies will be used. -

JackNaylorPE Three questions:Reply

1. Did I misread something or is there anything in there that addresses where it is now with regard to the low refresh range, especially at low end.

2. With all this coordination required between monitor manufacturers , AMD and Game Developers ... mostly the manufacturers and the increased panel specs, will FreeSync continue to be "free" ? It would seem that improving panel technology to address the described issues would have a cost associated with it.

3. Finally, any sign of MBR coming with Freesync ? This is the big separation between the two technologies in both performance and cost. With the top cards shooting for 60 fps at 2160p, @ 1440p, performance bottoms out at 80 fps in all but a few games, where many find using ULMB to be a better experience then G-Sync. Right now, it's up to the monitor manufacturers whether or not to add in the necessary hardware to add this feature resulting in a hodge podge of different quality solutions. A Freesync 3 where MBR is provided would truly allow AMD to go head to head with nVidia with this feature, but I think we would have to sday goodbye tot he Free part. -

JackNaylorPE Reply19097716 said:If you are on Monitor with 144+ Hz FreeSync and GSync are useless.

You would benefit from some reading as this is certainly not the case.

http://www.tftcentral.co.uk/articles/variable_refresh.htm

1. You are playing Witcher 3 at 62 - 70 fps on your 1070, why wouldn't you befit from G-Sync ?

When the frame rate of the game and refresh rate of the monitor are different,

By doing this the monitor refresh rate is perfectly synchronised with the GPU. You don’t get the screen tearing or visual latency of having Vsync disabled, nor do you get the stuttering or input lag associates with using Vsync. You can get the benefit of higher frame rates from Vsync off but without the tearing, and without the lag and stuttering caused if you switch to Vsync On.

2. You are playing Witcher 3 at 80 - 95 fps on your 1080, why wouldn't you befit from switching from G-Sync ULMB ?

G-sync modules also support a native blur reduction mode dubbed ULMB (Ultra Low Motion Blur). This allows the user to opt for a strobe backlight system if they want, in order to reduce perceived motion blur in gaming.

Suggest reading the whole article for an accurate description of what G-Syn / Freesync actually does. -

As I said free sync and gsync are useless if you do have 144+ Hz monitor. I have SLI 1080 and GSync makes no difference. As Monitors get better and we get to see 4k with 144Hz these technologies will be obsolete.Reply

In the other words, i play games using 144Hz refresh rate on Ultra Settings in resolution 1440p with vsync -> OFF, and gaming is just perfect with no screen tearing.

With monitors with low refresh rates Free Sync and GSync do help otherwise complete waste. I am still trying to understand what is actual purpose of Free Sync and GSync as i saw no benefit from it ever.

People can write whatever they want to, there are many other factors when it comes to game play.

The current games i play, Deus Ex Mankind Divided, Call of Duty Infinitive Warfare, Far Cry Primal, Rise of Tomb Raider. Since i do have SLI 1080 i run games on Windows 7 as Windows 10 is horrible platform for gaming in general. -

dstarr3 Reply19097716 said:If you are on Monitor with 144+ Hz FreeSync and GSync are useless.

People with high-Hz monitors are the people that need Free/G-Sync the most. If you have a 60Hz monitor, holding a steady 60FPS is a pretty easy task for most computers, so Hz sync isn't so useful because there aren't going to be a lot of fluctuations below that 60Hz. However, holding a steady 144FPS is a lot more challenging for computers. That's nearly three times the FPS. And framerate drops below that threshold are going to be a lot more frequent on even the most robust computers. So, absolutely, refresh sync is going to be very useful if you need to crank out that many frames per second, every single second. -

JackNaylorPE Reply19097873 said:As I said free sync and gsync are useless if you do have 144+ Hz monitor. I have SLI 1080 and GSync makes no difference. As Monitors get better and we get to see 4k with 144Hz these technologies will be obsolete.

1. Blame your eyes and / or lack of understanding of the technology. If you are running SLI'd 1080s at 144 Hz you are not running 4K which won't be capable of doing so until Display Port 1.4 arrives. Again, and understanding of what G-Sync offers would have you using ULMB instead of G-Sync with twin 1080s. You might want to try using the technology as recommended and switch to ULMB above 75 fps

It should be noted that the real benefits of variable refresh rate technologies really come into play when viewing lower frame rate content, around 40 - 75fps typically delivers the best results compared with Vsync on/off. At consistently higher frame rates as you get nearer to 144 fps the benefits of FreeSync (and G-sync) are not as great, but still apparent. There will be a gradual transition period for each user where the benefits of using FreeSync decrease, and it may instead be better to use a Blur Reduction feature if it is provided. On FreeSync screens this is not an integrated feature however, so would need to be provided separately by the display manufacturer.

And just because you have 144hz, and the GFX card performance to keep games above G-Sync range, doesn't make that statement true. Many people out there have 144 / 165 Hz monitors but not twin 1080s and they are operating in the 30 -75 fps range for the more demanding games... and here, having G-sync does clearly make a difference.

2. Now if you want to talk about "makes little difference", we can talk about SLI on the 10xx platform. SLI'd 970s was a proverbial "no brainer" over the 1080 with an average scaling of 70% at 1080p in TPUs Gaming test suite and 96 to > 100% in the most demanding games. For whatever reason, scaling on the 10xx series is now 18% at 1080p and 33% at 1440p. Several reason have been put forth as to why:

a) Devs choosing their priorities optimizing games for DX12 before spending tome on SLI enhancement.

b) CPU improvements in performance over the last 5 generations are about 1/3 of the performance improvement from the 10xx sereis alone.

c) With no competition from AMD for their SLI capable cards, improving SLI performance will accomplish only one thing ... increased sales of 1070s and a corresponding decrease in 1080 sale, the latter being where nVidia makes the most money.

I think you have to actually use the technology "as intended and recommended" before you complain that it has no impact. Again, G-Sync's impact is between 30 and 75 fps; FreeSync's impact is between 40 and 75 fps. Once past that threshold, the impact of this technology starts to wane .... this is not a secret and it in now way makes the technology obsolete. If we ignore MBR technology, G-Sync greatly improves the experience at 1080 p w/ a $200 GFX card; G-Sync greatly improves the experience at 1440 p w/ a $400 GFX card. Yes, you can certainly throw $1200 at the problem to get a satisfactory experience at 1440p w/o using G-Sync, but a 1070 w/ G-Sync leaves $800 in your pocket and works great. If you "overbuilt" anticipating what games might be like 3 years from now, then, nVidia gives you the opportunity to switch to ULMB, giving you the necessary hardware module as part of the "G-Sync package"

144 Hz allows use of the 100 Hz ULMB setting

165 Hz allows use of the 120 Hz ULMB setting

My son is driving a 1440p XB270HU with twin 970s ... he uses ULMB in most games but switched to G-Sync when the game can't maintain > 70 fps. When I visited him I played (65 - 75 fps) using both ULMB and G-Sync and found the experience extraordinary either way. -

elbert So freesync 2 has very little to do with freesync. Wonder why this wasn't just called GPU controlled HDR. Freesync with HDR.Reply -

Reply19098118 said:19097873 said:As I said free sync and gsync are useless if you do have 144+ Hz monitor. I have SLI 1080 and GSync makes no difference. As Monitors get better and we get to see 4k with 144Hz these technologies will be obsolete.

1. Blame your eyes and / or lack of understanding of the technology. If you are running SLI'd 1080s at 144 Hz you are not running 4K which won't be capable of doing so until Display Port 1.4 arrives. Again, and understanding of what G-Sync offers would have you using ULMB instead of G-Sync with twin 1080s. You might want to try using the technology as recommended and switch to ULMB above 75 fps

It should be noted that the real benefits of variable refresh rate technologies really come into play when viewing lower frame rate content, around 40 - 75fps typically delivers the best results compared with Vsync on/off. At consistently higher frame rates as you get nearer to 144 fps the benefits of FreeSync (and G-sync) are not as great, but still apparent. There will be a gradual transition period for each user where the benefits of using FreeSync decrease, and it may instead be better to use a Blur Reduction feature if it is provided. On FreeSync screens this is not an integrated feature however, so would need to be provided separately by the display manufacturer.

And just because you have 144hz, and the GFX card performance to keep games above G-Sync range, doesn't make that statement true. Many people out there have 144 / 165 Hz monitors but not twin 1080s and they are operating in the 30 -75 fps range for the more demanding games... and here, having G-sync does clearly make a difference.

2. Now if you want to talk about "makes little difference", we can talk about SLI on the 10xx platform. SLI'd 970s was a proverbial "no brainer" over the 1080 with an average scaling of 70% at 1080p in TPUs Gaming test suite and 96 to > 100% in the most demanding games. For whatever reason, scaling on the 10xx series is now 18% at 1080p and 33% at 1440p. Several reason have been put forth as to why:

a) Devs choosing their priorities optimizing games for DX12 before spending tome on SLI enhancement.

b) CPU improvements in performance over the last 5 generations are about 1/3 of the performance improvement from the 10xx sereis alone.

c) With no competition from AMD for their SLI capable cards, improving SLI performance will accomplish only one thing ... increased sales of 1070s and a corresponding decrease in 1080 sale, the latter being where nVidia makes the most money.

I think you have to actually use the technology "as intended and recommended" before you complain that it has no impact. Again, G-Sync's impact is between 30 and 75 fps; FreeSync's impact is between 40 and 75 fps. Once past that threshold, the impact of this technology starts to wane .... this is not a secret and it in now way makes the technology obsolete. If we ignore MBR technology, G-Sync greatly improves the experience at 1080 p w/ a $200 GFX card; G-Sync greatly improves the experience at 1440 p w/ a $400 GFX card. Yes, you can certainly throw $1200 at the problem to get a satisfactory experience at 1440p w/o using G-Sync, but a 1070 w/ G-Sync leaves $800 in your pocket and works great. If you "overbuilt" anticipating what games might be like 3 years from now, then, nVidia gives you the opportunity to switch to ULMB, giving you the necessary hardware module as part of the "G-Sync package"

144 Hz allows use of the 100 Hz ULMB setting

165 Hz allows use of the 120 Hz ULMB setting

My son is driving a 1440p XB270HU with twin 970s ... he uses ULMB in most games but switched to G-Sync when the game can't maintain > 70 fps. When I visited him I played (65 - 75 fps) using both ULMB and G-Sync and found the experience extraordinary either way.

As I said make no difference. Investing money into expensive monitor 144Hz and having $150+ dollar card is rather stupid. As far as SLI scaling on 1080 goes, what you said is just incorrect. SLI in DX12 does not work as DX12 is pile of crap, overhyped by MS. in fact doing nothing. I do gaming on Windows 7 because SLI scales there. I don't know what tests you were reading since everyone are using Win10 to test SLI, but in Windows 7 SLI on 1080 scales ~70%, in some games 90% like Battlefield. Newer titles like Watch Dogs 2 scales over 70%+. Windows 10 is broken at so many levels to start with but that is for some other discussion. My experience with vsync off and Gsync off is extraordinary as well. As I said it makes no difference. In fact less frames you push less it makes sense as tearing does not happen on something running 40FPS where Monitor refresh rate is 144Hz. You can say whatever you want...i am telling you my experience. More benefits you get by running game on NvMe M.2 drive with 2000Mb/s read than with free sync and gsync.

My second rig has Crossfire R390x and i really thought DX12 would benefit that setup under Windows 10, but not much...not worth going through hassles and bugs of Win10. Again free sync on that one is just useless. I tried it and got worse FPS.

You remind me of one of those people who wanted to argue with me that Windows 7 cannot boot from NvMe Samsung 950 Pro drive under UEFI and it doesn't support 10 Core CPU.

First thing i did after getting 10 Core CPU and 1080 SLI along with NvMe Samsung 950 Pro was to install Windows 7 on M.2 drive and booting from it. Funny thing is that even an argument of Win10 booting faster than Win7 is out of the way...

Don't believe everything you read.