MWC: Google Talks Projects Titan, Loon And Becoming An MVNO

At MWC today, Google's Sundar Pichai said that the company intends to offer wireless connectivity to customers in the United States. For now, Google remains conservative about its plans, but the new wireless service could actually be a Trojan horse meant to get carriers to become more competitive in the same way the company forced Google Fiber competitors to raise the Internet speeds or lower prices in areas where Google Fiber was installed.

"The core of Android and everything we do is to take an ecosystem approach and [a network would have] the same attributes. We have always tried to push the boundary with the innovations in hardware and software," Pichai said. "We want to experiment along those lines. We don't intend to be a network operator at scale. We are actually working with carrier partners. Will announce something in the coming months."

Earlier reports said that Google struck a deal with T-Mobile and Sprint to resell wireless services on their networks, essentially making Google an MVNO (mobile virtual network operator). Verizon and AT&T are unlikely to agree on a similar deal with Google, unless there's a concern that Google would have enough clout in the market to steal a significant portion of their customers.

Although the mobile carriers would still end up making money from having Google buy the service from them, they could make less; or once Google's service becomes popular, Google could decide to develop its own network and keep all of the customers it gained from the carriers.

Google may very well intend to do that, but the company isn't hinting at this, partly because Android phones being sold in the U.S. still rely heavily on the good will of the mobile operators that carry them. Therefore, Google isn't likely to make too many waves at this time.

"They know what we are doing," Pichai said. "In the end, partners like Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile and Sprint in the U.S. are what powers most of our Android phones. And the model works extremely well for us. And so there's no reason for us to course correct."

The company will initially focus on innovating on the technical side by actually running a wireless service itself. If Google discovers new innovations that could drastically lower the costs for carriers, that could also end up lowering prices for the carriers' customers.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

While the U.S. wireless market is much more difficult to navigate for Google right now, the company has found some success as a wireless provider in other places, such as Africa. Google has been working on Project Loon for the past two years, and last year it also acquired a drone company, called Titan Aerospace, to make flying drones that deliver Internet in remote areas.

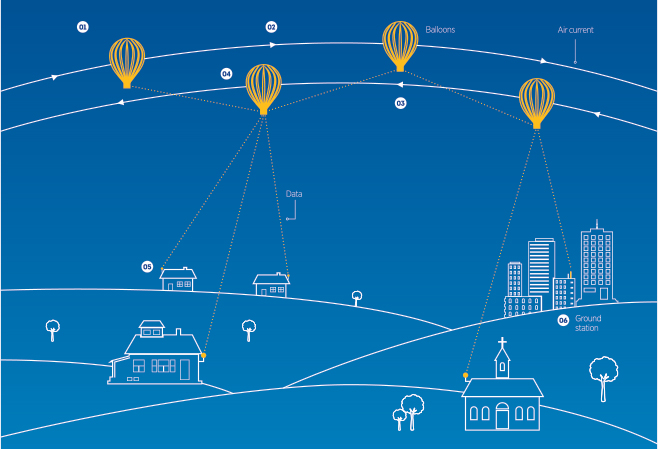

When Google launched the Loon balloons two years ago, the company could only keep them in the air for about three days before they would fall. Keeping them in the air is a difficult task because of the way the currents move. Google needs massive data sets from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to create advanced algorithms in order to predict how the balloons will react to changing atmospheric conditions in order to stay in the air for as long as possible.

Google reported that it is now able to keep the balloons in the air for more than six months. The company is now working with carriers in Africa and other places to provide Internet to those in remote areas where it is too cost prohibitive for mobile operators to install cables. Google's balloons are a much cheaper way to provide wireless service.

Plus, Google has switched from using Wi-Fi to using LTE, which makes it easier for carriers to integrate Google's wireless service into theirs, without cellphone subscribers noticing any difference. Baseband modem makers, such as Qualcomm, have also made this sort of integration easier recently, with new technologies that can seamlessly switch carriers even during a call to boost signal strength, or technologies such as LTE-U, which can be used in the unlicensed 5 GHz band instead of Wi-Fi.

Google's Project Titan is also making strides. Google acquired the drone-making company last year when it learned that Facebook was bidding for it. The Titan drones are supposed to stay in the air for up to five years, although this hasn't been put into practice yet.

According to Google, the Loon balloons and Titan drones could work together as a mesh network in the air. The drones would mainly be used during peak bandwidth hours to move where they are needed most. It's harder to do the same with the Loon balloons, which can only be moved up and down. Project Titan is still in the early days, though, and Google will begin testing the actual drones in a few months.

From Google Fiber to becoming an MVNO in the U.S., to trying to cover the whole of Africa (and perhaps later the world) with flying balloons and drones, it's clear that Google is very serious about becoming a global Internet provider.

Follow us @tomshardware, on Facebook and on Google+.

Lucian Armasu is a Contributing Writer for Tom's Hardware US. He covers software news and the issues surrounding privacy and security.

-

ZolaIII Google could actually perfect balloons & use them to place real satellites. This would actually provide much to everyone (who need to lunch satellite) as it would significantly cut cost & wile also staying green. This is not new idea.Reply -

alextheblue The drones are very interesting. However looking at a picture of one almost makes me want someone to shoot it down with a homemade remote piloted drone. I mean it just screams expensive sitting duck. I can't help but to feel that would be incredibly hilarious to read about... at least once. Same with the Amazon drones. "What do you mean my package was 'intercepted'?"Reply -

Calvin Huang They're called atmospheric satellites.Reply

Also, Loon balloons only reach 32 km up, which is 68 km short of space and 268 km short of the lowest satellite orbits. And even if a balloon could deliver a satellite to the right altitude, it wouldn't have anywhere near the 7.8 km/s orbital velocity required to stay up there. So as soon as the satellite gets released, it would just fall back to Earth and burn up. -

genz Calvin, you attach a horizontally firing rocket to the ballon. At the gravity level present at 100km, and the complete lack of atmosphere you could use a relatively small one, as we all know 90% of the fuel of every rocket we've ever put in space has been spent escaping earths atmoshpere.Reply -

Calvin Huang Reply15423016 said:Calvin, you attach a horizontally firing rocket to the ballon. At the gravity level present at 100km, and the complete lack of atmosphere you could use a relatively small one, as we all know 90% of the fuel of every rocket we've ever put in space has been spent escaping earths atmoshpere.

That would be possible theoretically. But you're overestimating the change in gravity and air density at those altitudes.

At 2000km, gravitational acceleration is still over half of what it is at sea level. Satellites aren't really trying to escape Earth gravity. They're in continuous free fall in fact. They just move at such a speed (over 7km/s ~= 15,658 mph) that they continuously fall beyond the curvature of Earth, balancing their inertia with gravity so that they don't drop in altitude and also don't fly off into space.

At 100km, the air density is much, much lower, but it's still over 4x as much as at actual satellite orbits. So it's still questionable that we can economically launch satellites with balloons, if we could even make them big enough to carry full-sized satellites + rockets and get them up to 100km.

In terms of fuel savings, the Saturn V used 38% of its fuel to get to 67km. But launching from that height wouldn't necessarily save you 38% of your fuel costs because a balloon's ascent adds very little to the inertia of your vehicle. In regular launches, that vertical inertia is built up by each stage of the rocket and then finally topped off and converted to horizontal orbital inertia by the final stage.

On top of that, you have to deal with the cost of expensive helium gas or use highly flammable hydrogen gas to inflate the balloon, which would have to be massive. And then there's the unpredictability of wind that may blow your balloon off-course.