The five best Intel CPUs of all time: Chipzilla's rise and fall and rise

Intel is kind of an underdog now.

Throughout its decades-long history, Intel has usually been at the forefront of computing thanks to its CPUs, often leading both our list of the best CPUs for gaming and the best CPUs for workstations. Good technology combined with often cutthroat and ruthless business tactics tends to build giants, and Intel is no exception. Even though the global firm is trying to fight its way back from a recent decline, its impressive victories from the good old days have prevented Intel's tech empire from crumbling to pieces in the face of powerful rivals like AMD and its potent CPUs.

Choosing Intel's five best CPUs is somewhat challenging because Intel has historically been in first place, and that raises the standard for what a great Intel CPU actually is. We've narrowed down what we think are Chipzilla's best processors since the company's founding, taking into account performance, value, innovation, and historical reputation. This is by no means an exhaustive list, and we don't doubt that we're going to skip over some great CPUs inadvertently.

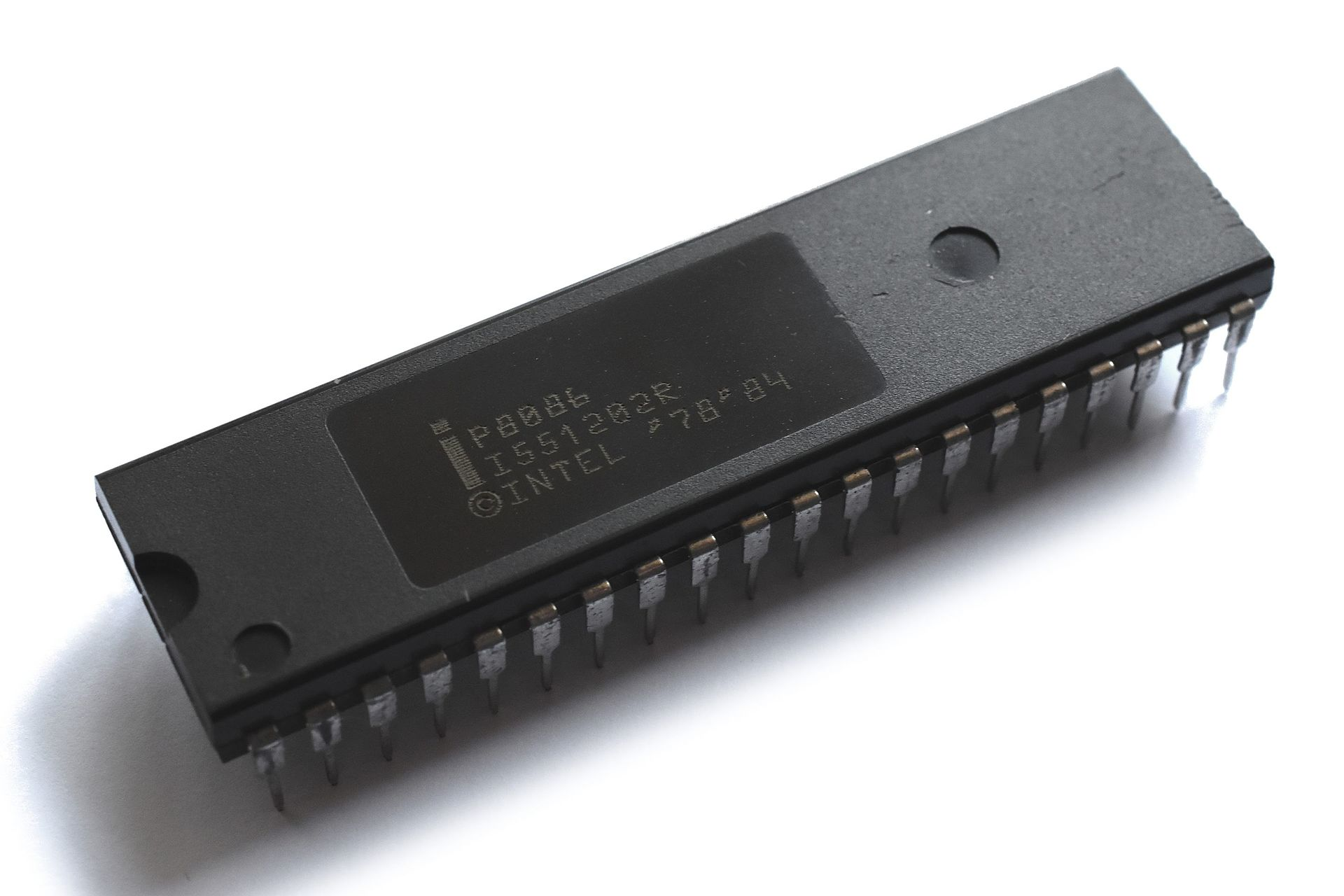

5 — Intel 8086: The age of x86 arrives

Founded in 1968, Intel was a pioneer in the nascent semiconductor industry. It started off as a memory designer and manufacturer, but it eventually began developing CPUs in the 1970s. The CPU business turned out to be much more promising for the company, as there were very few competitors, and it was easy to achieve world firsts, such as the Intel 4004, which Intel claims was the "first general-purpose microprocessor," which is to say it wasn't purpose-built like other processors.

With just four bits, the 4004 had lots of room for improvement, and in 1978, Intel launched its first 16-bit CPU, the Intel 8086 (you can see how this chip compares to more modern CPUs here). Though Intel used to claim this was the world's first 16-bit CPU, it wasn't — in fact, Intel was playing catch-up to companies like Texas Instruments, which had launched 16-bit chips sooner. Motorola's 68000 and Zilog's Z8000 also arrived the next year, turning up the heat even more.

Intel believed it could compete with the 8086, but it needed to convince the market to use it. Then-President and COO Andy Grove, Intel's third employee and later CEO, spearheaded a massive campaign called Operation Crush in 1980. According to author Nilakantasrinivasan J, "over a thousand employees were involved, working on committees, seminars, technical articles, new sales aids, and new sales incentive programs." $2 million was set aside for advertising alone, proclaiming "the age of the 8086 has arrived."

It was hoped that Crush would deliver Intel 2,000 design wins over the course of the year. Instead, Intel achieved between 2,300 and 2,500 wins (depending on who you ask). The 8086 transformed the company, and Intel sold off its memory business in 1986 to focus completely on CPUs. The 8086 captured 85% of the 16-bit processor market. This forever made the x86 architecture of the 8086 relevant, and it's still used for PCs and servers today, making Intel's marketing claims almost prophetic.

The massive success of the 8086 attracted the attention of IBM, which asked Intel to make a cheaper version for use in its upcoming Personal Computer. Intel came up with the cut-down 8088, which was 8-bit and not 16-bit. Regardless, the 8088-powered Personal Computer (or PC as it came to be known) was a resounding success and easily Intel's best design win with the 8086.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

As a side note, IBM was worried Intel wouldn't have enough 8088 chips for the Personal Computer, so it requested Intel find a partner to manufacture additional chips. Intel eventually settled on another company founded in 1968 that also made memory and CPUs: Advanced Micro Devices, or AMD for short. Though a partner in the 80s, Intel eventually attempted to cut AMD out of the picture in the 90s, which resulted in AMD winning rights to the x86 architecture, creating a potent rival.

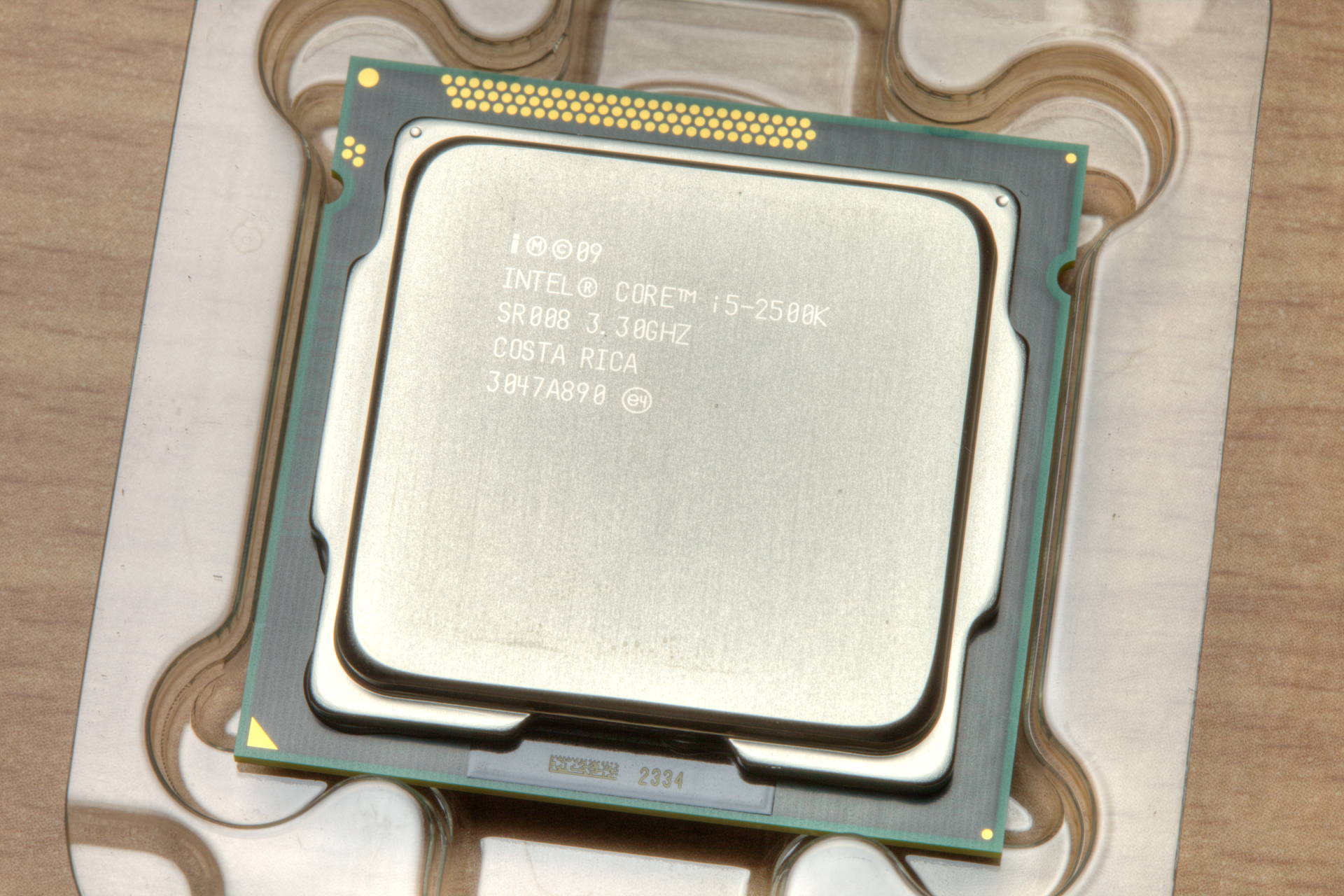

4 — Core i5-2500K: That time Intel won so hard that AMD gave up for half a decade

It didn't take too long for AMD to become a big thorn in Intel's side. Much of the 2000s were really painful for Intel as its NetBurst and Itanium architectures were killed by Athlon and Opteron. However, it didn't take long for Intel to regain the edge, technologically with its Core 2 CPUs, and financially with marketing funds of questionable legality. By the end of the 2010s, AMD was on the back foot while Intel was gaining momentum.

For the next generation, Intel shot first in January 2011 with its new 2nd-Gen CPUs powered by the new Sandy Bridge architecture. These CPUs weren't exactly a revolution compared to 1st-Gen since they still capped out at four cores for the mainstream desktop and only had a minor update to Intel's turbo boost technology. Still, there were some key upgrades: the 32nm node (though some 1st-Gen CPUs also used 32nm), roughly 10% or so higher IPC, and Quick Sync video encoding.

Perhaps the most noticeable innovation with Sandy Bridge was its unification of the CPU die and the die for integrated graphics and the memory controller. While Intel and AMD are back to putting graphics on a separate chip for some processors, back then, combining both pieces of silicon into one was a big step forward, especially for the memory controller.

In our 2nd-Gen review, we found that Sandy Bridge wasn't a massive upgrade in any particular category but instead offered a variety of improvements across the board; compared to 1st-Gen, it was decently faster, somewhat more power efficient, and had Quick Sync, which not even AMD or Nvidia had an answer to. The quad-core Core i5-2500K, in particular, was a great CPU thanks to its price tag of $216, a steal compared to the $317 Core i7-2600K, which also had just four cores (though it did have double the threads thanks to Hyper-Threading).

While 2nd-Gen Core didn't exactly reshape the landscape of CPUs, AMD now had an even bigger mountain to climb if it wanted to stand a chance. It took AMD until October to respond, almost a year later, and they were unquestionably bad both at the time and in hindsight. Even though AMD's top-end FX-8150 with eight cores (sort of) was only a little more expensive than the 2500K, we thought the 2500K was still the better chip.

Despite how clearly awful AMD did with Bulldozer, few predicted it would effectively mark AMD's exit from the high-performance CPU market, even for the mainstream. For the next five years, Intel called the shots and reaped the rewards, while AMD came perilously close to bankruptcy around 2015 (or at least that was a big fear at the time). If you wanted a well-rounded CPU with good performance in the early to mid-2010s, you were almost certainly buying an Intel CPU.

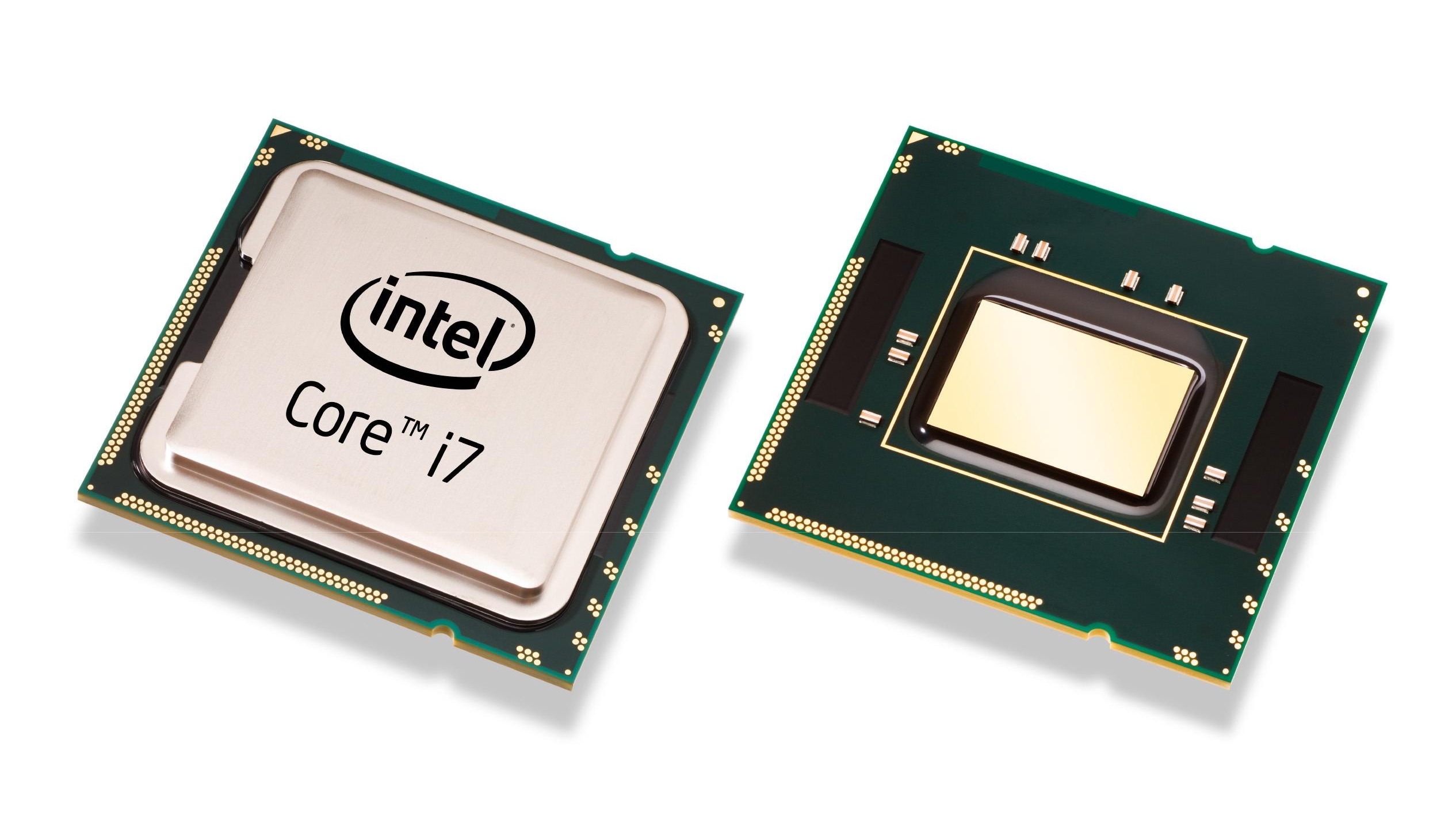

3 — Core i7-920: Doing what AMD did, just better

Though Core 2 put Intel firmly back in first place for the first time in years, the company's position wasn't entirely secure. After all, the Core architecture wasn't exactly carefully planned and executed, as Intel was in a hurry to replace its NetBurst-based Pentium 4 lineup with something actually competitive. Core 2 still held the lead even after AMD launched its new Phenom lineup in 2007, but if Intel wanted to stay ahead and keep selling, it would need a new series of CPUs.

Of all its shortcomings, two were particularly important to solve. First, Core 2 Quad CPUs were made with two dual-core chips, as the original Core architecture wasn't designed with four cores in mind since it was based on mobile Pentium M silicon. Additionally, Intel had to abandon Hyper-Threading technology that gave each core two threads instead of one, and that was also because Pentium M didn't have that feature, while later Pentium 4 CPUs did.

With the brand-new Nehalem architecture introduced in 2008, Intel finally had true quad-core CPUs with Hyper-Threading and also added a third level of cache and clock boosting technology. Architecturally, it was actually quite similar to what AMD did with K10-based Phenom CPUs, but with more refined execution. Nehalem's more advanced 45nm node was also a nice advantage.

Intel's new generation of Nehalem-powered CPUs ushered in the age of the Core i and launched with three Core i7 CPUs, of which the Core i7-920 was the obvious mainstream choice given its price tag of $284. Though clocked at just 2.66GHz, much lower than the $999 i7-965 Extreme at 3.2GHz, the i7-920 was very capable and beat even the fastest Core 2 Extremes in just about every benchmark in our review, often by significant margins.

Intel had made its comeback with Core, and with 1st-Gen CPUs, that comeback was set to last. Flagship to flagship, Intel's Core i7-965 Extreme was 64% faster than AMD's Phenom X4 9950 Black Edition. It probably stung for AMD, considering that Phenom beat Intel to the punch by doing four cores on one piece of silicon and implementing an L3 cache. Even Phenom II CPUs with six cores couldn't even the score for AMD, which was no longer the Pentium-killing company it had once been.

Intel went further than just quad-core CPUs, though, and offered even higher core counts. Initially, these were six- and eight-core models limited to Xeon servers, and they use two quad-core chips, essentially a repeat of Core 2. However, once Intel shrunk Nehalem down to 32nm, it created a true six-core chip and even a ten-core CPU as well, the world's first. Intel was perhaps more ahead of AMD than ever before, and the gap would continue to widen over the next eight years.

2 — Core i9-13900K: Bringing a tough fight to a draw

In the decade following the launch of Sandy Bridge-based 2nd-Gen CPUs, Intel had a hard time measuring up to its past, launching CPUs that, at best, were alright. At first, this was because Intel just wasn't incentivized to compete since AMD was mostly out of the picture, but when AMD made its comeback with Ryzen in 2017, it was already too late for Intel. The company's 10nm node was delayed over and over for years, and Intel's edge slipped until it was in second place in many categories from 2019 onward. 10nm was only truly viable in 2021 with the launch of 12th-Gen Alder Lake CPUs.

Though Alder Lake comfortably beat Ryzen 5000, it could only do so a year after Ryzen 5000's launch, which meant AMD's next generation was already on the horizon. This put Intel in a tricky position because its 7nm/Intel 4 CPUs were nowhere close to being done. They relied on lots of cutting-edge and novel technology anyway, which was risky to put out in front of AMD's tried-and-tested Ryzen chips. Intel didn't want to be late again or lose, yet both seemed mutually exclusive.

But in the past few years, while AMD was racking up wins, Intel learned two important lessons: increasing core count dramatically in a single generation was a winning strategy, and boosting the amount of cache was great for gaming performance. Intel already had a good CPU in its hands, and making a version with more cores and cache wouldn't take much time, and it could potentially rival AMD's next generation (though it would undoubtedly increase power draw).

The 2022 CPU showdown started with Ryzen 7000's September launch, and AMD's new flagship Ryzen 9 7950X was much faster than the Ryzen 9 5950X and Core i9-12900K. This wasn't surprising since AMD had switched to TSMC's cutting-edge 5nm node, massively increased power consumption, and got a little extra IPC too. It was up in the air whether 13th-Gen Raptor Lake CPUs could even get in striking distance, because the Core i9-13900K's only significant upgrades were eight extra E-cores instead of more P-cores, which were faster, more L2 and L3 cache, and higher clock speeds.

Despite all the on-paper problems, the Core i9-13900K proved to be just as fast as the 7950X when it launched in November. In our review, the 13900K was just barely behind the 7950X in productivity workloads and actually beat it in gaming by a decent margin. The fact that Intel could match AMD's performance was impressive on its own, but 13th-Gen also beat AMD in price. The CPUs themselves were pretty cheap, and combined with discounted LGA 1700 600-series motherboards and DDR4 RAM, you could build a 13th-Gen PC for very cheap.

Meanwhile, Ryzen 7000 CPUs were relatively expensive for their performance level, didn't cover the lower end of the market (and still don't to this day), required expensive and brand-new AM5 600-series motherboards, and DDR5 memory, which cost more than DDR4 by a substantial amount. Ryzen 7000's two selling points were efficiency and its longer upgrade path, which are important but not the be-all-end-all.

Although 13th-Gen has technically been superseded by 14th-Gen, both use the Raptor Lake architecture and since 13th-Gen is cheaper, it's generally the better buy. AMD has since resolved some of the pricing issues of Ryzen 7000 and AM5 motherboards, but Ryzen 7000 is still usually more expensive. Both companies plan on releasing brand-new architectures and CPUs later in 2024, which will be the end of this generation.

1 — Core 2 Quad Q6600: Athlon's vanquisher

The early to mid-2000s were tough for Intel. On the PC side of the business, NetBurst-based Pentium 4 was a disaster thanks to its high power consumption and inability to successfully clock as high as Intel needed, leading to the 4GHz Pentium 4 and the successor CPU Tejas being canceled. The lucrative server business was arguably worse, as Intel had sunk billions of dollars into Itanium, which was incompatible with the x86 software ecosystem that Intel itself had nurtured. When AMD introduced Opteron with a 64-bit version of the x86 architecture, it was over for Itanium.

To keep the market in its favor, Intel was spending billions upon billions in marketing expenses to Dell, HP, and other OEMs to keep them from using AMD, which earned Chipzilla worldwide fees and penalties. This wasn't a sustainable strategy (and its legality was also questionable, obviously), and since both NetBurst and Itanium were dead ends, Intel needed a new architecture, and fast.

Luckily for Intel, it did have another architecture it could use. Intel's Haifa team worked on the 2003 Pentium M lineup for laptops. Luckily for Intel, Pentium M was largely based on Pentium III and not Pentium 4, meaning it was much more efficient. However, as it was made for laptops, Intel would have to do some work to make it suitable for desktops and servers. Most notably, Intel made Core 64-bit and retained the x86 architecture, just like AMD did with Athlon 64. Alongside these technological changes, Intel also made a name change to the architecture, renaming it Core.

Core technically launched as a laptop-exclusive lineup in early 2006, but it was quickly superseded in just a few months by Core 2, which was made for both laptops and desktops. On paper, Core 2 actually seemed like a downgrade; the original Core 2 Duo CPU based on Conroe had a lower clock speed, less L2 cache, and even dropped the cutting-edge Hyper-Threading feature. Despite all that, Core 2's higher IPC proved to be killer in our Core 2 Duo review, where even the slowest E6600 almost always beat the fast Pentium 4 and Athlon 64 CPUs.

However, Intel had even greater performance ambitions and launched Core 2 Quad CPUs with four cores in January 2007. Core was only designed for two cores, so to make the first quad-core CPUs ever, Intel just put two of its dual-core chips in the same package. The Q6600 was the first quad-core desktop CPU you could buy, and although it initially launched at an eye-watering $851, by August, it was cut down to a mere $266. Its high performance and relatively low price at the time allowed it to become one of Intel's most popular CPUs ever.

Intel's scrapped-together quad-core totally preempted AMD's upcoming Phenom CPUs, which boasted quad-core CPUs that didn't need to rely on multi-chip workarounds. However, when Phenom launched, it was clear that Intel's jankier chip design was better. The Phenom 9700 was almost 13% slower than the Q6600 in our review, not to mention all the other faster quad-cores Intel had launched, too. Even the quad-core Phenom II X4 in 2009 struggled to beat the Q6600, which was based on technology from 2006.

Core 2 was legendary despite all the on-paper problems: the original architecture was never meant for desktops and servers, it could only go up to two cores on one chip, and it got rid of Hyper-Threading, just to name the big ones. Although the dark cloud of Intel's dubious marketing practices hangs over Core 2 (and arguably 1st and 2nd Gen, as well), it's almost certain that neither Phenom nor Phenom II would ever beat Intel's CPUs. Intel undeniably had the edge here, and it secured the company's first-place position that it would own for about 13 years, ending only when Ryzen 3000 arrived.

Honorable mention: Alder Lake

Much like how in the 2000s Intel nearly killed itself by trying to create a 10GHz Pentium 4, Intel's turmoil in the late 2010s and early 2020s was because it nearly killed itself trying to compress almost a decade of process advancements into just a couple of years. Intel's 10nm node was a disaster: it missed its original 2015 launch date, arrived in 2018, and was clearly very broken, and then powered laptop-exclusive Ice Lake and Tiger Lake CPUs from 2019 to 2021.

By contrast, AMD was racking up wins in 2019 and 2020. Ryzen 3000 thrashed Intel's 9th-Gen lineup, Ryzen 4000 basically made Intel's mobile CPUs obsolete, and Ryzen 5000 handily beat Intel's 10th-Gen in games, taking away Chipzilla's last talking point for why its CPUs are the best. For people who were sick of the same desktop lineup year after year since 2nd-Gen came out, it was pretty cathartic.

With Ryzen 5000, AMD introduced price bumps, and its cheapest CPU, the Ryzen 5 5600X, started at $300. Sure, these new chips were fast, but they didn't have AMD's classic value advantage, and you couldn't even upgrade if you didn't have $300 to spare. It kind of just seemed like one greedy company was traded for another, and it became pretty clear that AMD winning this hard actually wasn't that great after all.

Thankfully, Intel finally got its act together in 2021 and launched its 12th-Gen Alder Lake CPUs. This lineup featured brand-new hybrid CPUs with two types of cores, a new architecture, a working 10nm node, PCIe 5.0 support, and compatibility with both DDR4 and DDR5. The flagship Core i9-12900K came with 16 total cores, putting it at parity with AMD's Ryzen 9 5950X. In our review, the 12900K won a clear victory in multi- and single-core applications and a narrow win in gaming. The 12900K was also only $589 to the 5950X's $799, making it the clear winner overall.

Unbelievably, though, AMD had not updated its Ryzen 5000 lineup since it launched in late 2020; that meant the cheapest CPU was still $300. By contrast, Intel planned to launch a flurry of budget options in January 2022, like the Core i5-12400. AMD's response was cut-down chips with mediocre performance and value, a shocking ball drop for a company that used to be the value king.

Of course, Alder Lake was a year late into the generation, and AMD eventually launched better value models, lowered prices, and released the cutting-edge Ryzen 7 5800X3D with 3D V-Cache. With that in mind, it's hard for 12th-Gen to make it onto the list, especially with 13th-Gen proving Alder Lake could have been more. What's even more amazing is that Intel was competitive with a node that was supposed to launch in 2015. If Intel didn't try and pack nearly a decade of improvements into two or so years of development and instead spread out those advancements across multiple generations, Chipzilla would probably still be Chipzilla in more than name.

Matthew Connatser is a freelancing writer for Tom's Hardware US. He writes articles about CPUs, GPUs, SSDs, and computers in general.

-

Roland Of Gilead Ah, the Q6600. I love that CPU. I had it on an Asus P5N-E sli. To OC it, you only had to change the FSB from 266mhz to 333mhz. This bumped the CPU clocks from 2.4ghz up to 3ghz without breaking sweat. It could go further with a lower multiplier (8x instead of 9 x). 3.2 was reachable with 400mhz ram, but it took testing to get it right. There was an fsb hole somewhere between 333mhz and about 380/390. Once you got past that 3.2 was very achievable. Stellar CPU IMO.Reply

The CPU was in a Commodore PC. They rebranded as a PC gaming PC supplier. I had a medal of honour theme skin on it. It looked deadly! : https://commodoregaming.com/pcshop/Game+PC/Commodore+gs.aspx

The link is just for reference. The specs of the one I had don't seem to be there any more. -

pjmelect Undoubtedly the best CPU for its time and was the chip that made Intel was the 8080 yet it was not mentioned in this article.Reply -

bit_user I know better than to click on an article like this, but I fell for it. Now, I guess I swallowed the bait, because I'm also posting.Reply

4. Core i5-2500K: That time Intel won so hard that AMD gave up for half a decade

Any article about this period that doesn't also talk about Intel's manufacturing advantage is bordering on journalistic malpractice. It's easy to forget, but Intel had literally a couple years lead on the manufacturing tech of anyone else in the chip game, and Sandybridge probably came right at the peak of that. Intel's lead was so bad that I was strongly of the opinion that Intel should've been forced to spin off its fabs, which looks like it could finally happen for other reasons.

No doubt AMD had other things going wrong with it, but even a comparable design from them wouldn't have been competitive due to Intel's superior node. I think AMD knew this, and it's one of the factors that motivated some bad decisions on their part, like the FPU-sharing of Bulldozer and hoping they might be able to compete with GPU-compute (i.e. the whole HSA debacle - look it up).

The only way AMD CPUs managed to regain relevance is both that Intel's 7 nm fab node hit years worth of delay, allowing TSMC to catch up & even pass them, and AMD finally waking up and adopting a properly modern architecture (many thanks to Mike Clark and Jim Keller, for that). Here's what Jim said about the latter point:

"Mike Clark was the architect of Zen, and I made this list of things we wanted to do . I said to Mike that if we did this it would be great, so why don’t we do it? He said that AMD could do it. My response was to ask why aren't we doing it - he said that everybody else says it would be impossible. I took care of that part. It wasn’t just me, there were lots of people involved in Zen, but it was also about getting people out of the way that were blocking it."

Source: https://www.anandtech.com/show/16709/an-interview-with-tenstorrent-ceo-ljubisa-bajic-and-cto-jim-keller

Even though it was executed successfully, Zen could not match Skylake's IPC. The first gen was only relevant due to having double the core count. It took further generations of refinement and a properly competitive TSMC node for AMD to briefly pass Intel on single-thread performance. -

v2millennium ReplyIntel came up with the cut-down 8088, which was 8-bit and not 16-bit.

8088 was 16-bit CPU with 8-bit data bus. -

gondor I believe 80386 and P6 (Pentium Pro) belong on top 5 bst INtel CPU list of all time - much more so than Nehalem and some random Raptor Lake mentioned.Reply -

HideOut You honerstly gave the 13900K over the 12900K? Its the same chip! 12xxx series is the new chips, witht he 13ths gaining 100-200 mhz. the ONLY exception is the 13700 that gained 4 e cores. The list here is flawed, very very flawed. And the 2600K was much more known than the 2500K. I truely dont get many of the picks on this list.Reply -

cyrusfox Reply

Recency bias, what's factually true vs what majority of readers can relate to in article form.gondor said:I believe 80386 and P6 (Pentium Pro) belong on top 5 bst INtel CPU list of all time - much more so than Nehalem and some random Raptor Lake mentioned.

Personally I was an AMD user starting with an Athlon in 1999 to Phenom II X2 variants till 2012 when it was clear AMD was inefficient and not improving. I sidestepped Bulldozer and switched to Intel on Ivy bridge(i5-3570k which I did not upgrade until 8th gen, and have since bought every i7/i9 of each subsequent generation). I personally don't remember any CPU's used prior to 1999 as I didn't build those machines and was too young(we were a Mac house). I think our first PC was a Free compaq PC received with early DSL bundle from 1996, I loved it as it gave me access to games that usually were delayed if ever they came to macs (Warcraft 2/Diable/Starcraft, Doom, Quake, etc...)

the 13900 added 8e cores over the 12900 as well as much more cache, its a substantially better chip for productivity task and has an edge on the 12900 due to the increased cache.HideOut said:You honerstly gave the 13900K over the 12900K? Its the same chip! 12xxx series is the new chips, witht he 13ths gaining 100-200 mhz. the ONLY exception is the 13700 that gained 4 e cores. The list here is flawed, very very flawed. And the 2600K was much more known than the 2500K. I truely dont get many of the picks on this list. -

stonecarver It might be an snuffed at aged CPU today but it's still hanging in there is the Xeon 5680 and the 5690. Launched in 2010-11Reply

It was there on the first Gen i3/ i5/i7's to now Intel's 14 gen. It quietly rolled through all the punches and the advancements of both Intel and AMD.

There 14 year old CPU's now that's a long run. I would give this chip the Energizer bunny award for it keeps going and going. :ouimaitre::)

And it runs Windows 11 beautifully. -

baflgv20 The 8700K (10600K), 9900K (10700K), 10900K are all honorable mentions. The Q6600 is definitely a great selection. I still have my Q6600 GO and eVGA 680 SLi rev.2 board with the 1200MHz SLi OCZ DDR2 which is the fastest DDR2 if i'm not mistaken. But, the 8700K to the 10900K's are still great CPU's. I got an 8700K with a z370 AORUS Gaming 7 and RX 6900XT TOXIC "AIR" on a 65' 4K120Hz LG OLED and it works wonders. I also have a 77in OLED wall with a AORUS 4090 and 13700K but, i find myself always going back to the z370 setup. Maybe it's the Corsair 500D RGB SE with 6 LL120's and the z370 Aorus Gaming 7. It looks like a Christmas tree in the winter. I put it in the window for all the children to see....lol. I ran a P4 631 OC'd to 4GHz on an Abit AG8 with the uGuru OC chip (who remembers that). I then went to the Q6600 GO and eVGA 680i to a 3770K. Which i let my pops use. So i basically use the Q6600 OC to 3.6GHz all the way up till the i7 8700K caught my attention. I found a returned 8700K for $280 in Jan 2018. So i jumped on it. I also got the z370 Aorus Gaming 7 board for $150 since the IO shield was missing. I ended up getting the shield for $12 later. I'm the guy that buys out all the open box and returns from Micro Center...lol. I recently picked up $720 3090ti's FE's. ASUS TUF versions for the same. Also, $700 7900XT's to $500 6950XT's. Who wouldn't. The best deal i ever got was a $1200 4090 Aorus WaterForce with a $1200 4K120 LG OLED because the box was damaged and the hoses were disconnected. Got to love Micro Center's open box and returns or refurbished products.Reply -

UnforcedERROR Reply

My Q6600 was at 3.6 stable for years until the RAM went bad. My board also didn't properly support more than 4 gigs at the time, which is mostly what aged it out. I had it so long the next processor I bought was, oddly, a 6600K. Wasn't intentional, just the timing.Roland Of Gilead said:Ah, the Q6600. I love that CPU. I had it on an Asus P5N-E sli. To OC it, you only had to change the FSB from 266mhz to 333mhz. This bumped the CPU clocks from 2.4ghz up to 3ghz without breaking sweat. It could go further with a lower multiplier (8x instead of 9 x). 3.2 was reachable with 400mhz ram, but it took testing to get it right. There was an fsb hole somewhere between 333mhz and about 380/390. Once you got past that 3.2 was very achievable. Stellar CPU IMO.

The 2500K is one of the best value-oriented chips Intel produced. For over a decade people joked about not needing anything more than their overclocked 2500K. It was kind of the successor to the Q6600 in that sense.HideOut said:And the 2600K was much more known than the 2500K. I truely dont get many of the picks on this list.