The five best AMD CPUs of all time: From old-school Athlon to brand-new Ryzen

AMD's bread and butter.

Although AMD makes CPUs, GPUs, and now FPGAs, it's really the first one on that list that has been the core of AMD's business and identity for much of its history. Though AMD and its CPUs were frequently in underdog status in the Intel vs AMD war, today it looks less and less true, and it's definitely thanks to a string of great CPUs the company has made recently, getting AMD back to where it was on its legendary streak in the 2000s and helping it score top ranks in our list of the Best CPUs for gaming.

Given that AMD has been making competitive CPUs for over two decades now, it's not easy to choose just five that have been great — there have been numerous models that perform well in our CPU benchmarks. We considered the competitiveness and reputation of not only individual chips, but their wider CPU family as well. We've ranked our five choices from bottom to top and ended with an honorable mention.

5 — Athlon XP 1800+: A revolution in performance and nomenclature

AMD was founded in the same year as Intel, but early on, it was clear that Intel was the leading figure in the emerging semiconductor industry. In fact, much of AMD's early success rested on partnering with Intel, where AMD acted as a second source for Intel CPUs. When Intel first introduced its x86 processors and got IBM to use them in its legendary Personal Computer (AKA the PC), IBM stipulated that Intel had to team up with another manufacturer to ensure there was enough supply. Intel chose AMD, which would end up being incredibly consequential.

AMD went from a second source to a fully independent CPU manufacturer after a legal battle against Intel that ultimately resulted in AMD's acquisition of equal rights to the x86 architecture. Though AMD started out with clones of Intel CPUs, it eventually moved on to making its own custom architectures with K5 and later K6. However, the company couldn't catch up with Intel's top-end Pentium series with these architectures.

The third try was the charm for AMD with its K7 architecture, which powered AMD's original Athlon CPUs. These new AMD chips outright beat Intel's Pentium III processors, and not only that, they were even faster at the same clock speed. Back in those days, frequency was usually the only thing that mattered as long as CPUs had plenty of cache, but AMD's K7 showed architectural design mattered, too. The K7 was so potent because it could also scale to high frequencies, and AMD reached the 1 GHz mark before Intel, all thanks to the K7 and the Athlon.

When Intel introduced its Pentium 4 CPUs to retake the crown, it didn't follow AMD's lead but rather doubled down on high clock speeds and lower instructions-per-clock (IPC). K7 had plenty of gas left to meet Intel's new NetBurst architecture, though, and AMD's brand-new Athlon XP CPUs really cemented the fact that the Athlon would remain a contender for first place for a long time. The initial flagship, the Athlon XP 1800+, won most benchmarks against Intel's 2 GHz Pentium 4 chip in our review, and this was despite Intel striking back with both a new architecture and higher frequencies.

Athlon XP was also a turning point in how CPUs were named. By this point, K7 had gained so much of its performance lead thanks to architectural innovations that the 1800+ could beat the 2 GHz model of the Pentium 4 despite only having a clock speed of 1.5 GHz. AMD decided that it would be shooting itself in the foot if it continued to differentiate and name CPUs based solely on clock speed. The model names of Athlon XP CPUs were based on how closely they performed to competing Intel models, with 1800+ meaning it was about equivalent to a 1.8 GHz Pentium 4.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

In the end, K7 and Athlon carried AMD for four years, albeit with several updates and upgrades. Athlon XP gradually lost its supremacy as Pentium 4 continued to get faster models with ever higher clock speeds, but nevertheless, it was competitive and built on top of the original Athlon CPUs to deliver AMD a fairly long period of victory. It's quite rare nowadays that a single architecture can stay viable for such a long amount of time, and K7 was uniquely potent despite its age.

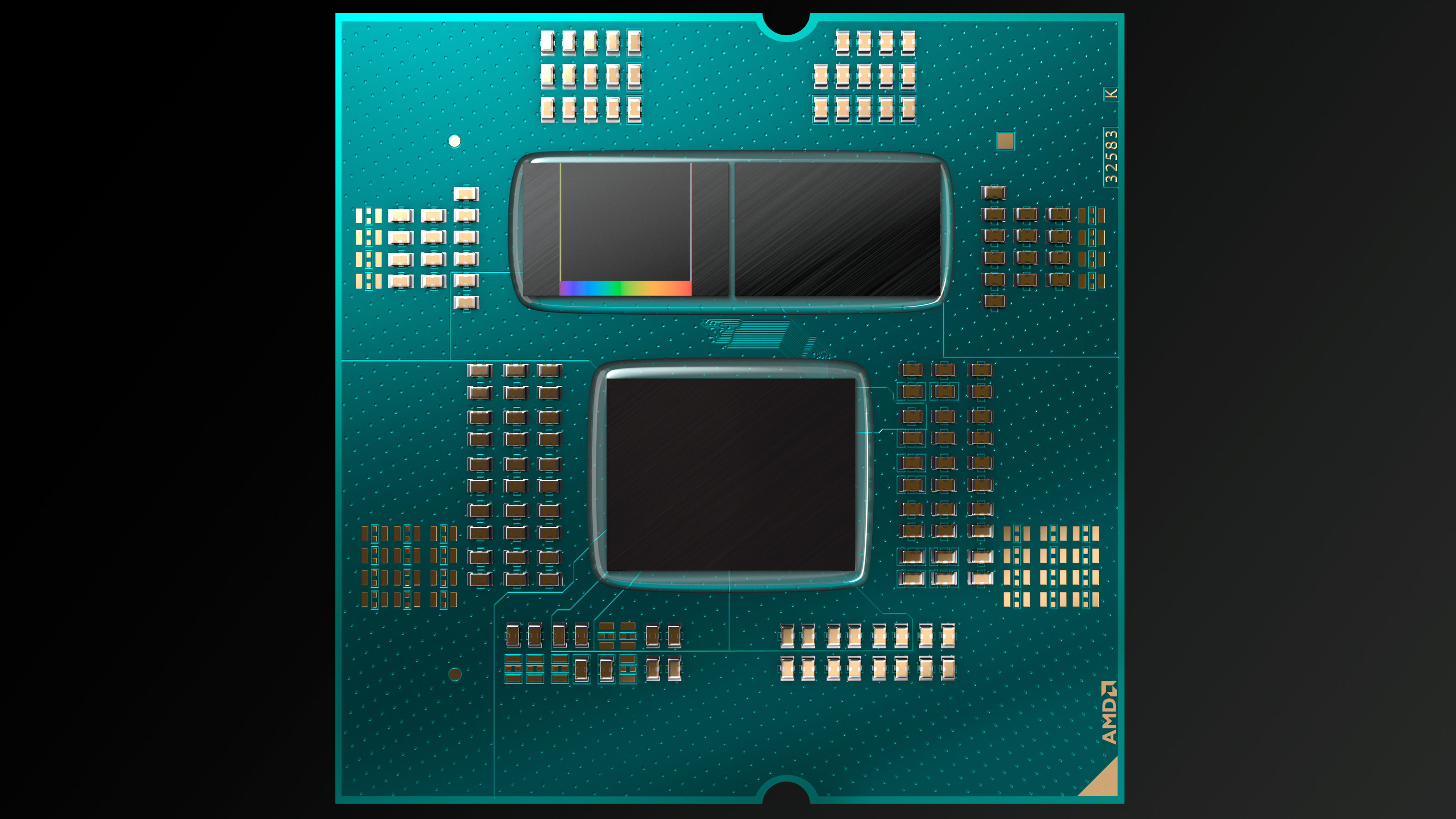

4 — Ryzen 7 7800X3D: The ultra-efficient and better-value gaming flagship

Today, AMD enjoys a position that isn't unlike the one it had in the classic Athlon days. Arguably, its Ryzen 7000 CPUs are in the lead in several key categories over Intel's competing 14th-Gen and Core Series 1 chips, and this is just the continuation of a mostly uninterrupted streak of wins. Ryzen 7000, like Athlon XP, was built on top of the achievements of its predecessor, and much of the strength of Ryzen 7000's Zen 4 architecture is thanks to Zen 3.

AMD introduced some key innovations with its Zen 3 architecture for the Ryzen 5000 series and Epyc Milan server CPUs. It featured one unified block of L3 cache for more consistent core-to-core latencies and 20% higher IPC, both of which were good but expected improvements. However, there was one addition AMD didn't utilize immediately: data links that enabled a secondary chip full of nothing but cache to be placed on top of the CPU chiplets. It was already known that more cache was always better, but how much better could a CPU really be if it was just beefed up with more cache?

The Ryzen 7 5800X3D proved cache could add tons of performance to a CPU. Released a year and a half after the debut of Ryzen 5000, the 5800X3D was almost identical to the regular 5800X but came with 64MB of L3 cache. It punched way above its weight against the Ryzen 9 5950X and Core i9-12900K in games, often matching and sometimes beating both. Unfortunately, it was more of a proof-of-concept, as (at the time) it was the only Ryzen 5000 CPU with 3D V-Cache, had reduced clock speeds, and was on the soon-to-be-phased-out AM4 socket.

Ryzen X3D really hit its stride with the Ryzen 7000 series, and AMD wasted no time and resources for its second generation of Ryzen X3D CPUs in 2023. This time around, AMD launched a full lineup: the Ryzen 9 7900X3D and 7950X3D to start off with, followed by the Ryzen 7 7800X3D a couple of months later. Launching these chips very early into Ryzen 7000's life span made a really big difference, as you wouldn't be left wondering if it was worth buying a 7000X3D chip if the next generation was just around the corner.

Of the three 3D V-Cache chips launched, the Ryzen 7 7800X3D at the bottom is arguably the best of all. Sure, it only has eight cores, and it also has the lowest clock speeds of the bunch; the 7900X3D and the 7950X3D can achieve much higher clock speeds by utilizing their second chiplet that doesn't have a cache chiplet installed on the top. However, its gaming performance speaks for itself, and in our review it edged just a tiny bit ahead of the much more expensive 7950X3D. Plus, this power-efficient CPU was capped out at a mere 65 watts.

Although the 7800X3D can certainly be overkill for gaming, it's undeniably a great CPU overall. It has great performance and power efficiency and can beat much more expensive CPUs in gaming. Today, the 7800X3D retails for about $400, far cheaper than the Ryzen 9 7950X3D at $650 and the Core i9-14900K at $550. It's just an obvious choice for anyone who wants as many frames as possible, and it's super efficient as a bonus. 3D V-Cache is certainly a trendsetter for gaming CPUs, and it looks like increasing L3 cache will become a common strategy in the future.

3 — Ryzen 7 1700: AMD's triumphant return to competition

The first half of the 2010s saw AMD enter a depressing decline. Its fortunes had turned for a variety of reasons since the heyday of Athlon 64 in the mid-2000s, leading to worsening finances thinly spread across both its CPU and GPU projects. AMD was back to firmly being in second place with its Phenom CPUs, and the succeeding generations of Bulldozer-based FX processors put to rest any ideas of AMD being remotely competitive with Intel at the cutting edge. In 2015, many predicted that AMD would go bankrupt.

Despite it all, AMD still planned for a future where the company could get back on its feet, launch competitive CPUs, and even beat Intel. The Bulldozer architecture was more or less scrapped in favor of something that was both traditional and also radical. This new architecture would follow Intel's lead on high single-threaded performance and simultaneous multi-threading. It would also be capable of serving nearly the entire CPU market with just a single chip. Codenamed Zen, AMD hoped this would be the CPU that could revive the company.

It wasn't just AMD that had lots of hope for Zen. Despite Intel's performance lead, the PC gaming community had soured on the blue team due to increasingly poor generational gains. AMD leaned into this negativity and turned it into hype for its upcoming Zen-based gaming CPUs. No expense was spared; AMD titled its late 2016 reveal for Ryzen "New Horizon," got Geoff Keighly to open the livestream, and brought in dozens of journalists for the CPU's early 2017 launch. People were excited, but it could be a double-edged sword if Ryzen didn't impress.

On launch day, it was clear that the Ryzen 1000 was not perfect. The flagship Ryzen 7 1800X could certainly deliver a 60 FPS gaming experience, but Intel's competing 7th Gen CPUs could do better than that. But if people were looking for a value champion, the Ryzen 7 1700 was the ultimate chip. For a mere $330, you could buy a CPU rivaling Intel's high-end desktop class Core i7-6900K in almost anything multi-threaded. The 6900K retailed for $1,100 and required a super-expensive motherboard, making the 1700 the obvious choice. The 1700 was also good enough for gaming, didn't consume much power, and could be overclocked for more speed.

The real genius behind first-generation Zen wasn't merely that it was close to catching Intel but that it rethought the way processors were made. The traditional way to tackle the processor market was to take an architecture and make a few different chips based on it to cover the needs of every segment. Instead, AMD designed a single Zen CPU that could be connected to other CPU chips on a single package. Not only was it economical, but it made it very easy to make big CPUs. Of course, AMD didn't abandon its APUs and made one or two other Zen chips with integrated graphics; otherwise, its product stack was based on a single chip.

Before Zen, AMD's largest server CPU had 16 cores. By putting four Zen CPUs on a single package, AMD could boost this up to 32. It also got back into the high-end desktop arena with 16-core Threadripper CPUs. The turnaround for AMD was nothing short of a miracle. You could finally buy a good AMD CPU, and the mood for CPUs became far more optimistic than in the past five years.

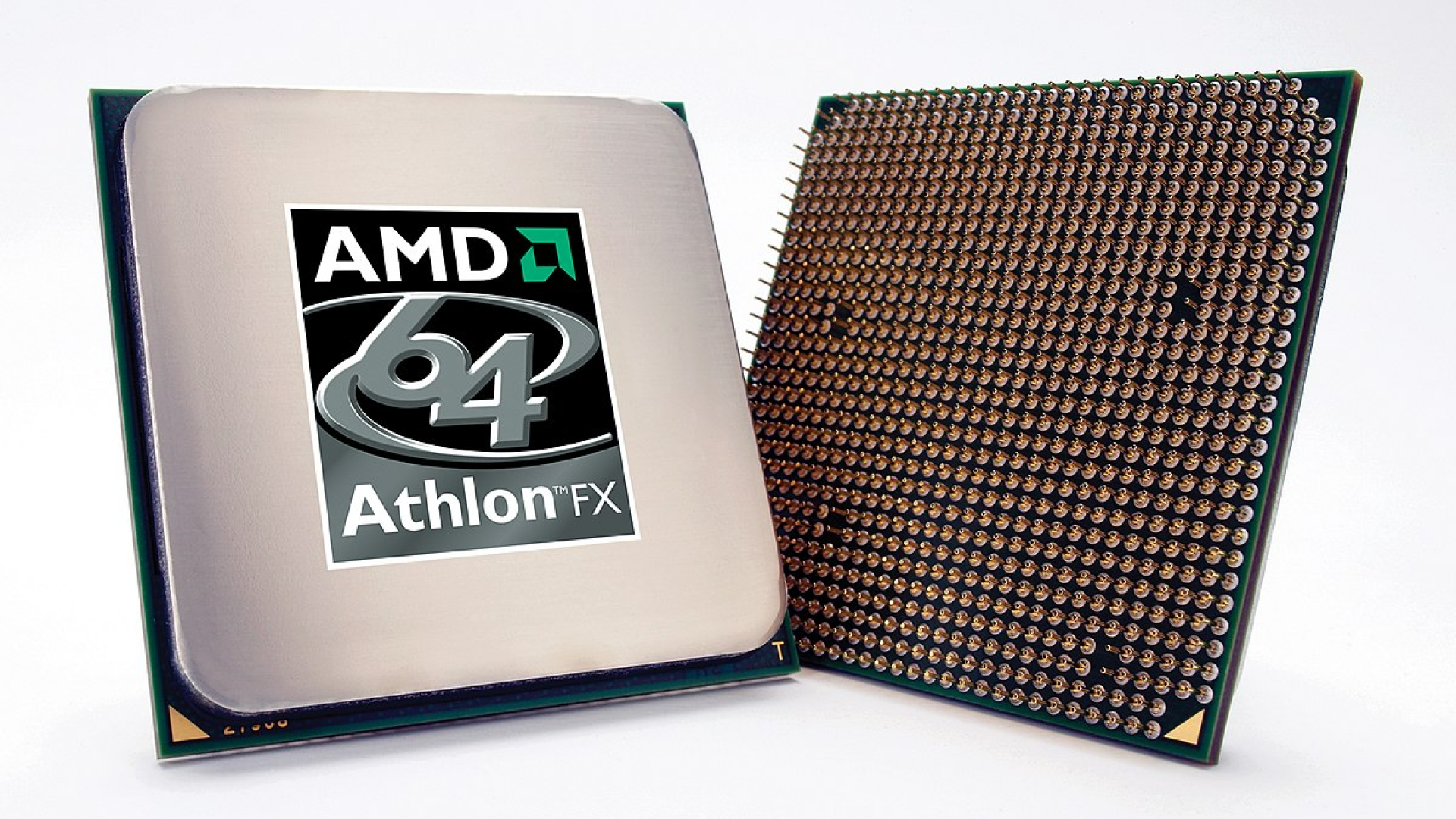

2 — Athlon 64 3000+: Putting NetBurst and Itanium into early retirement

Although the K7-powered Athlon was wildly successful for AMD, the gap between it and Intel's newer Pentium 4 chips grew as Intel outpaced AMD in the clock speed race. More than that, 64-bit computing was emerging, and Intel had beaten AMD to it with its Itanium server CPUs. However, Pentium 4 was a power hog, and Intel had abandoned its x86 architecture with Itanium. Itanium could not natively run the 32-bit, x86 software that dominated the landscape,

AMD seized on Intel's weaknesses with its K8 architecture. The company doubled down on its balanced approach to clock speed and IPC and ensured K8 had decent efficiency. When it came to support for 64-bit computing, AMD didn't follow Intel's lead and make its own custom architecture. Instead, AMD just made a 64-bit version of x86 and called it AMD64. To be clear, it wasn't hard to do this, but Intel decided against it because x86 had issues. But to AMD, making AMD64 was easy and could utilize the vast library of x86 programs.

The launch of the AMD64-powered K8 architecture was a two-pronged attack, starting with Opteron server CPUs in April 2003. The new AMD64 server chips performed very well against Intel's x86 Xeons, based on the same silicon as its Pentium 4 processors. In September came the Athlon 64, and although it mostly just caught up to Intel in performance and price, it nevertheless brought AMD back to parity alongside introducing 64-bit for regular PCs.

While the flagship Athlon 64 FX-51 and Athlon 64 3200+ weren't that impressive for price and performance, the Athlon 64 3000+ was, at last, what people were waiting for. For just $218, the world of 64-bit computing was open for many, and the market took note. HP discontinued its Itanium workstations in late 2004, which effectively killed Itanium workstations as HP was the last to distribute them. At the start of 2005, Microsoft then killed its Itanium version of Windows, the first 64-bit Windows OS. An AMD64 version was launched just a few months later.

At this point, Itanium was effectively dead, and Pentium 4 was Intel's last bastion. Unfortunately for the company, Intel's gamble on increasing frequency rather than IPC proved to be a fatal error, and it discovered too late that its plans for 10 GHz were very impossible. Intel even had problems launching a 4 GHz Pentium 4, which was eventually canceled. Intel had to settle for a 3.8 GHz model in late 2004 that only matched AMD's flagship Athlon 64 FX-55, with a much higher power draw. It was the end of the road for NetBurst-powered Pentium 4 CPUs.

Given that Itanium is dead and the AMD64 instruction set eventually came to be called x86-64, it's safe to say AMD won this round. However, AMD wouldn't get to reap the financial rewards of its technological victory. From 2002, Intel had been giving generous deals and rebates to OEMs like Dell and HP as long as they didn't do any or merely limited business with AMD. Intel was sued and fined internationally, though notably wriggled out of a $1 billion fine by the European Union. Ultimately, AMD's business suffered greatly and wouldn't recover for about two decades.

1 — Ryzen 9 3950X: The mouse eats the elephant

Ryzen got AMD back on the board, but its first- and second-generation products didn't exactly return AMD to the Athlon days. When Intel launched its 9th-Gen CPUs in late 2018, AMD no longer had a core count advantage and was behind in everything but value. Instead of incrementally upgrading Ryzen, AMD invested its limited resources into Zen 2, a big generational leap the company hoped could compete with Intel's upcoming 10nm Cannon Lake CPUs.

Intel launched its first 10nm CPU in 2018, the Core i3-8121U, and one thing was clear: 10nm was a disaster. The node was already three years late, but the low-end and poor-performing 8121U was the best Intel could do. Zen 2 was designed to maybe match Cannon Lake and even utilized TSMC's cutting-edge 7nm node, but the actual competition would be aging 14nm CPUs based on 2015's Skylake architecture. Going into 2019, people weren't wondering if AMD would win; they were wondering by how much.

Zen 2 was, in many ways, an upgraded Zen, featuring beefier cores with 15% more IPC and twice the L3 cache. Though these were pretty big improvements, they weren't the star of the show; chiplets were the big-ticket feature introduced with Zen 2. Each Zen 2 CPU had two different types of chiplets: a compute chiplet with the CPU cores, and an I/O chiplet with connectivity hardware and other functions. Chiplets reduced the redundancy seen in original Zen CPUs and allowed AMD to push core counts even more.

Thanks to chiplets, AMD could offer more cores than ever before. Equipped with 16 cores running at high clock speeds, the Ryzen 9 3950X was practically an HEDT CPU, and it steamrolled the Core i9-9900K in multi-threaded workloads. AMD even caught up in gaming, which had been a safe category for Intel CPUs for many years. 9th-Gen CPUs had very little reason to exist from this point on. The 3950X and its 12-core sibling, the 3900X, even threatened Intel's HEDT CPUs, which could only boast features like having more PCIe lanes.

Zen 2 was an even bigger threat in HEDT and servers. For these segments, Threadripper and Epyc CPUs were equipped with a massive I/O die and up to eight chiplets, for a total of 64 cores. Even Intel's flagship 28-core Xeons looked ancient next to AMD's new 64-core CPUs, which were faster and significantly more efficient. The Threadripper 3990X was almost twice as fast as Intel's competing Xeon W-3175X, which had been about 70% faster than the Threadripper 2990WX.

By the end of the Zen 2 generation in late 2020, AMD had more market share than ever since 2007. In respect to performance and efficiency, Intel remained in dead last until late 2021, with its launch of 12th Gen Alder Lake CPUs. That's two and a half years spanning two generations of Ryzen CPUs and three generations of Intel CPUs where AMD was largely the better choice. It wasn't an Athlon moment for AMD; it was better than that.

Honorable mention — Bobcat and Jaguar

Much of AMD's success story is rooted in how it overcame its financial crisis in the 2010s, which could have potentially led to bankruptcy. AMD had an acute disadvantage in both CPUs and GPUs, which effectively made up all of its business. However, throughout these hard years, there was one product line that AMD could rely on: its big cat APUs, primarily Bobcat and Jaguar. These were essentially AMD's only consistently successful processors until Zen came out in 2017.

While AMD and Intel had traditionally competed in the desktop, laptop, and server markets, in the 2010s, the two attempted to expand into a fourth area: low-power computing. This included stuff like smartphones, appliances, mini-PCs, and tablets. You've probably heard of Intel's Atom CPUs, which tried (and failed) to conquer Arm. AMD, too, had its own version of Atom, though with far less ambitious plans and aimed to merely compete in laptops, tablets, and tiny PCs.

When Bobcat, AMD's first-ever APU, first came onto the scene in 2011, AMD's Bulldozer CPUs were losing on all fronts. Unlike its siblings in other markets, Bobcat could totally beat Intel's competing CPU, the Atom. The E-350 was miles ahead of the Atom 330, with AMD gaining the lead in both single- and multi-core performance. In integrated graphics, the E-350 was twice as fast, and there was basically no contest there. Bobcat could scale to a much higher power draw than Atom, making the AMD APU much faster, yet it was still just as efficient, if not more.

AMD sold millions upon millions of Bobcat chips, easily making it the company's most-sold processor in the Bulldozer era. By 2013, it had apparently sold 50 million units. That was, of course, thanks to Bobcat's super-low price, but nevertheless, it was a wildly successful product, finding use in mini-PCs and laptops alike.

Bobcat was replaced with Jaguar, which had the distinction of being the APU of choice for the PS4 and Xbox One. An all-AMD console gaming solution was very appealing since it had both high-performance CPU and GPU technology, and Jaguar avoided the clunky dual-vendor solution in the PS3 and Xbox 360. As for PCs, Jaguar was pretty much on par with Intel's Ivy Bridge, even though Jaguar was on 28nm and Ivy Bridge was on 22nm, which is a big deal for efficiency.

Although these APUs are largely remembered as poor performers and largely uninteresting, they were also AMD's most successful products for several years. They weren't designed to be fast but power-efficient, and that's what made them so successful. These APUs gave AMD the lifeline that it desperately needed, especially the consistent income from Jaguar-powered console sales. Bobcat and Jaguar really ought to be remembered as the products that saved AMD's bacon when its desktop, laptop, and server CPUs couldn't.

- MORE: Best CPUs for Gaming

- MORE: CPU Benchmark Hierarchy

- MORE: AMD vs Intel

Matthew Connatser is a freelancing writer for Tom's Hardware US. He writes articles about CPUs, GPUs, SSDs, and computers in general.

-

kiniku Very informative piece that goes back down memory lane. I remember for quite some time when INTEL was THE CPU brand name. The trusted, "you can't go wrong..." choice. But AMD delivered the 64bit era to desktop PCs, and made multi-cores both affordable and common. Versus Intel trying to milk 6+ cores with their rather expensive "HEDT" components. Thanks to AMD, the Steam charts speak for themselves and developers are responding to 6-12 core CPUs on the average desktop.Reply

We have much to be grateful for today as PC consumers thanks to AMD. -

Bigbluemonkey33 Why in the world would the Amd athlon thoroughbred not be on this list?Reply

If there was no thoroughbred, none of the rest of these would have happened. The K6 was awful and the athlon absolutely dismantles the P3 and was still competitive with p4 depending on the benchmarks. -

Dr3ams There is quite a few years in between my current AMD CPU and the last one I used. Since I built my first PC in 1995, I've used both AMD and Intel CPUs.Reply

Here's the AMD CPUs I still have. I also owned a K6-2 333, but I don't know where that is at the moment. (I'm old)

AMD Ryzen 5 5600X 3.7 GHz - release date 2020AMD K8 Athlon 64 3200+ 2.0 GHz - release date 2005AMD K8 Athlon 64 2800+ 1.8 GHz - release date 2003AMD Sempron 2200+ 1.5 GHz - release date 2004AMD K7 Athlon XP 2400+ 2.0 GHz - release date 2002AMD K7 Athlon 850 MHz - release date 2000 -

Bigbluemonkey33 The K7 was revolutionary (thoroughbred). It beat p3. The one thing comparable is when Intel hit the wall around the 1000k and 1100k series and amd poured on with Ryzen series. Specifically the 3000k 5000k series.Reply -

Nikolay Mihaylov Very desktop centric. IMO the most important (and therefore, the best) CPU from AMD is the original Opteron, some 20-ish years ago . It introduced the 64-bit extentions and heralded the death ot Itanium. And it introduced Integrate Memory Cotroller - something we take for granted these days.Reply -

Bigbluemonkey33 Reply

That absolutely should be in the conversation. I was addressing the desktop market because that's what the original article seemed to be addressing.Nikolay Mihaylov said:Very desktop centric. IMO the most important (and therefore, the best) CPU from AMD is the original Opteron, some 20-ish years ago . It introduced the 64-bit extentions and heralded the death ot Itanium. And it introduced Integrate Memory Cotroller - something we take for granted these days. -

Roland Of Gilead Reply

'If I have seen further, it is because I'm standing on the shoulder of Giants!' - Isaac NewtonBigbluemonkey33 said:Why in the world would the Amd athlon thoroughbred not be on this list?

If there was no thoroughbred, none of the rest of these would have happened. The K6 was awful and the athlon absolutely dismantles the P3 and was still competitive with p4 depending on the benchmarks.

Yes, you could argue that chip was a pre-cursor. Agree with you there. -

Roland Of Gilead Reply

Had the K8 2800+ and paired it with a 9700 Pro. I couldn't believe the bump in performance. Really let my 9700 Pro shine.Dr3ams said:There is quite a few years in between my current AMD CPU and the last one I used. Since I built my first PC in 1995, I've used both AMD and Intel CPUs.

Here's the AMD CPUs I still have. I also owned a K6-2 333, but I don't know where that is at the moment. (I'm old)

AMD Ryzen 5 5600X 3.7 GHz - release date 2020AMD K8 Athlon 64 3200+ 2.0 GHz - release date 2005AMD K8 Athlon 64 2800+ 1.8 GHz - release date 2003AMD Sempron 2200+ 1.5 GHz - release date 2004AMD K7 Athlon XP 2400+ 2.0 GHz - release date 2002AMD K7 Athlon 850 MHz - release date 2000 -

COLGeek My first AMD CPU was a 386DX-40, it far surpassed the Tandy 1000 TL I had been using just before. Great CPU at the time.Reply -

Vanderlindemedia Slot A (Any model) with a GFD.Reply

Socket A, any model with esp "AXIA" stamped onto it's core.

Athlon XP with simple pencil mod.

FX from 3.2Ghz stock to 5GHz for free.

Oh man. AMD offered so much value for the money back then.