AMD Fusion: How It Started, Where It’s Going, And What It Means

You've already read about APUs, and maybe you're even using them now. But the road to creating APUs was paved with a number of struggles and unsung breakthroughs. This is the story of how hybrid chips came to be at AMD and where they’re going.

Fusion Ignites

Throughout this shuffling of top office name plates, AMD engineers continued their dogged pursuit of Fusion. What began as a team of four people—former ATI vet Joe Macri, the recently deceased AMD fellow Chuck Moore, then-graphics CTO Eric Demmers (now at Qualcomm), and AMD fellow Phil Rogers, who was the group’s technical lead—had grown to envelop the top three layers of engineers from both the CPU and GPU sides of the company. Macri describes the early phase of their collaboration as "the funnest five months I’ve ever had." The first 90% of the Fusion effort was an executive engineer’s dream. "The last 10% was excruciating pain in some ways."

"That effort resulted in a couple of things," adds Macri. "One, we ended up with the best architecture out there that’s unifying scalar and vector compute. It blows away what [Intel] did with Larrabee. The Nvidia guys have only attacked part of the problem, because they only have the IP portfolio to attack part of the problem. What they’ve done isn’t bad. It’s actually good for having one hand tied behind their back. But with [Fusion], we had the full IP capability, and it truly is the first unified architecture, top to bottom."

Technical architecture aside, AMD developed something else: a cohesive, merged company. Out of the pressure and pain of Fusion development emerged a different company than either of the two that had gone into it. The old days of talking about "red" and "green" teams were finally gone.

"We were similar in that we were both in a major fist fight with one guy," says Macri. "I think ATI had the fairer fight in that we were up against a similarly-sized company [Nvidia]. But this had a lot of impact on design and implementation cycles. Now, the guys at AMD had won a number of times, but it was more like David and Goliath [Intel]. It was like, 'Wow, we actually beat Goliath!' With ATI, we’d been in a fist fight for many years with Nvidia, and we won as many as we lost. So we had a different attitude about winning. ATI needed to learn that there were some Goliaths out there, and you have to be pretty damned smart to beat a Goliath. AMD learned that it actually was a Goliath in certain cases. It could be an equal. Now merge that with some faster time to market strategies. Today, our product cycle time is faster than ever across the board. So the melding gave both sides a better ability to attack not just their traditional competitors but also new competitors coming up. And those new guys coming up aren’t big. They’re all kind of small. They’re all AMD-sized. I don’t think AMD ever would have had the right attitude on how to beat someone their own size without inheriting ATI. And I don’t think ATI could have figured out how to beat someone several times bigger without AMD’s attitude of asking how you aim where the other guy’s not aiming."

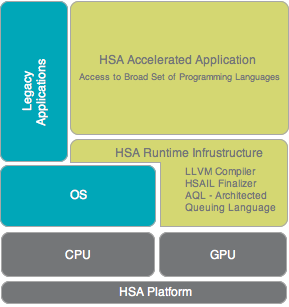

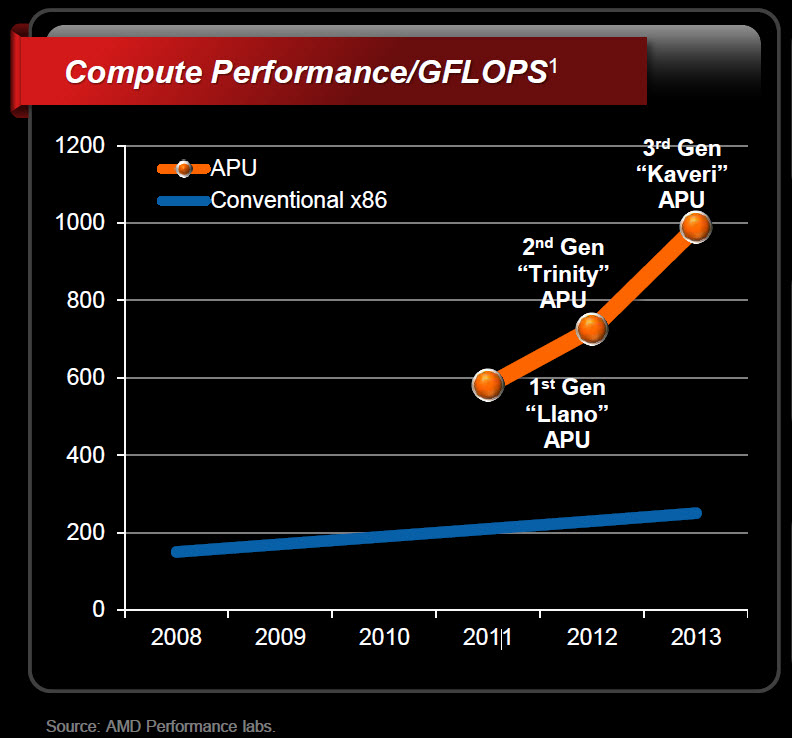

Just as the two organizations were completing their cultural fusion, the Fusion effort itself was nearing the end of its first stage. AMD showed its first Fusion APUs to the world at CES in early 2011, and product started shipping shortly thereafter. In the consumer space, the Llano platforms, based on the 32 nm K10 core, arrived in the A4, A6, A8, and E2 APU series. Another announcement from 2011 CES was that the Fusion System Architecture would henceforward be known as the Heterogeneous System Architecture (HSA). According to AMD, the company wanted to turn HSA into an open industry standard, and a name that didn’t reflect a long-standing AMD-centric effort would help illustrate that fact. This would prove to be the first hint of AMD’s even larger aspirations.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

-

mayankleoboy1 Wont the OS have to evolve along with the HSA to support it? Can those unified-memory-space and DMA be added to Windows OS just with a newer driver?Reply

With Haswell coming next year, Intel might just beat AMD at HSA. They need to deliver a competitive product. -

Reynod Great article ... well balanced.Reply

I think you were being overly kind about the current CEO's ability to guide the company forward.

Dirk Meyer's vision is what he is currently leveraging anyway.

A company like that needs executive leadership from someone with engineering vision ... not a beancounter from retail sales of grey boxes.

History will agree with me in the end ... life in the fast lane on the cutting edge isn't the place for accountants and generic managers to lead ... its for a special breed of engineers.

-

jamesyboy AMD is the jack-of-all-trades and the master-at-none. Even the so called "balancing" that they're supposed to be doing is already being done better by Nvidia, ARM, and now Intel with Medfield. AMD doesn't stand a chance trying to bring a ARM like balance to the x86 field. I have no idea what they were thinking when they decided that they'd rather be stuck in between mobile and desktop. They have all of this wonderful IP, all those wonderful engineers. I fear that what's best for AMD will be to leave the x86 battlefield all together, and become a company like Qualcomm or Samsung, and leverage their GPU IP into the Arm world--i fear this because a world where Intel is the only option, is one that's far worse off for the consumer.Reply

They don't have the efficiency of Ivy Bridge, or Medfield, they don't have the power of Ivy Bridge, and they're missing out on this round of the Discrete Graphics battle (they were ahead by so far, but nvidia seems to have pulled an Ace out of their butt with the 600 series). So what exactly IS AMD doing well? HTPC CPUs? Come on! The adoption rate for the system they're proposing with HSA is between 5 and 10 years off....and because they moved too early, and won't be able to compete until then, they have to give the technology away for free to attract developers.

Financially, this a company's (and a CEOs) worst nightmare...they're too far ahead of their time, and the hardware just isn't there yet.

This will end of being just like the tablet in the late '90s, and early '00s. It won't catch on for another decade, and another company will spark, and take advantage of the transition properly, much to AMD's chagrin.

I'm not sure if it was the acquisition of ATI that made AMD feel like it was forced to do this so early, but they aren't going to force the market to do anything. This work should have been done in parallel while making leaps and bounds within the framework of the current model.

You can't lead from behind.

I've always been a fan of AMD. They've brought me so e of the nicest machines I've ever owned...the one that had me, and still have me most excited. But I have, and always will buy what's fastest, or best at the job I need the rig for. And right now...and for the foreseeable future, AMD can't compete on any platform, on any field, any where, at anytime.

AMD just bet it's entire company, the future of ATI (or what was the lovely discrete line at AMD), the future of their x86 platform, and their manufacturing business all on something that it wasn't sure it would even be around to see. They bet the farm on a dream.

Nonetheless, i disagree that you were being overly kind about the CEOs ability to lead the company. I think you're being overly kind for thinking this company has a viable business model at all. Theyll essentially have to become a KIRF (sell products that are essentially a piece o' crud, dirt cheap) f a compay to stay alive.

This is mostly me ragin at the fail. The writer of this article deserves whatever you journalist have for your own version of a Nobel.

This was a seriously thorough analysis, and by far the best tech piece i've seen all year. We need more long-form journalism in the world, for i her way too many people shouting one line blurbs, with zero understanding of the big picture.But i have to say, that while this artucle is 98% complete, you missed speaking anout the fact that this company is a company...an enterprise that survives only with revenue. -

A Bad Day I really enjoyed this article.Reply

Now, does anyone want to play Crysis in software rendering with max eyecandy? -

army_ant7 @jamesyboy:Reply

It's not over until the fat lady sings. As I read your post, I felt that you were missing a (or the) big point of the APU and this article.

It's about how software is developed nowadays and how there is such a huge reserve of potential performance waiting to be tapped into. I could imagine that if future software bite into this "evolution" to more GPGPU programming then I would expect a huge jump in performance even on the current, or shall I see currently being phased out, Llano APU's.

Yes, current discrete GPU systems would improve in performance as well significantly I would think, but to the same degree that APU's would improve, especially with the new technologies to be implemented like unifying memory spaces, etc? I don't think so.

I'm not saying that you're totally wrong. AMD might end up croaking, but we can't say for certain 'til it happens. Don't you agree? :-) (I'm not picking any fights BTW. Just sharing my thoughts.) -

blazorthon jamesyboyAMD is the jack-of-all-trades and the master-at-none. Even the so called "balancing" that they're supposed to be doing is already being done better by Nvidia, ARM, and now Intel with Medfield. AMD doesn't stand a chance trying to bring a ARM like balance to the x86 field. I have no idea what they were thinking when they decided that they'd rather be stuck in between mobile and desktop. They have all of this wonderful IP, all those wonderful engineers. I fear that what's best for AMD will be to leave the x86 battlefield all together, and become a company like Qualcomm or Samsung, and leverage their GPU IP into the Arm world--i fear this because a world where Intel is the only option, is one that's far worse off for the consumer.They don't have the efficiency of Ivy Bridge, or Medfield, they don't have the power of Ivy Bridge, and they're missing out on this round of the Discrete Graphics battle (they were ahead by so far, but nvidia seems to have pulled an Ace out of their butt with the 600 series). So what exactly IS AMD doing well? HTPC CPUs? Come on! The adoption rate for the system they're proposing with HSA is between 5 and 10 years off....and because they moved too early, and won't be able to compete until then, they have to give the technology away for free to attract developers.Financially, this a company's (and a CEOs) worst nightmare...they're too far ahead of their time, and the hardware just isn't there yet.This will end of being just like the tablet in the late '90s, and early '00s. It won't catch on for another decade, and another company will spark, and take advantage of the transition properly, much to AMD's chagrin.I'm not sure if it was the acquisition of ATI that made AMD feel like it was forced to do this so early, but they aren't going to force the market to do anything. This work should have been done in parallel while making leaps and bounds within the framework of the current model.You can't lead from behind.I've always been a fan of AMD. They've brought me so e of the nicest machines I've ever owned...the one that had me, and still have me most excited. But I have, and always will buy what's fastest, or best at the job I need the rig for. And right now...and for the foreseeable future, AMD can't compete on any platform, on any field, any where, at anytime.AMD just bet it's entire company, the future of ATI (or what was the lovely discrete line at AMD), the future of their x86 platform, and their manufacturing business all on something that it wasn't sure it would even be around to see. They bet the farm on a dream.Nonetheless, i disagree that you were being overly kind about the CEOs ability to lead the company. I think you're being overly kind for thinking this company has a viable business model at all. Theyll essentially have to become a KIRF (sell products that are essentially a piece o' crud, dirt cheap) f a compay to stay alive.This is mostly me ragin at the fail. The writer of this article deserves whatever you journalist have for your own version of a Nobel.This was a seriously thorough analysis, and by far the best tech piece i've seen all year. We need more long-form journalism in the world, for i her way too many people shouting one line blurbs, with zero understanding of the big picture.But i have to say, that while this artucle is 98% complete, you missed speaking anout the fact that this company is a company...an enterprise that survives only with revenue.Reply

Funny, but last I checked, AMD's Radeon 7970 GHz edition is the fastest single GPU graphics card for gaming right now, not the GTX 680 anymore. Furthermore, AMD can compete in many markets in both GPU and CPU performance and price. AMD's FX series has great highly threaded integer performance for its price (much more than Intel) and the high end models can have one core per module disabled to make them very competitive with the i5s and i7s in gaming performance. Going into the low end ,the FX-4100 and Llano/Trinity are excellent competitors for Intel. Some of AMD's APUs can be much faster in both CPU and GPU performance than some similarly priced Intel computers, especially in ultrabooks and notebooks where Intel uses mere dual-core CPUs that either lack Hyper-Threading or have such a low frequency that Hyper-Threading isn't nearly enough to catch AMD's APUs. Is this always the case? No, not at all. However, you ignore this when it happens (which isn't rare) and you ignore many other achievements of AMD.

As of right now, there is no retail Nvidia card that has better performance for the money (at least when overclocking is concerned) than some comparably performing AMD cards anymore. The GTX 670 ca't beat the Radeon 7950 in overclocking performance and it can't beat the 7950 in price either. The GTX 680 is no more advantageous against the Radeon 7970 and 7970 GHz Edition. I'm not saying that these cards don't compete well or that they don't have great performance for the money (that would be lying), but they don't win outside of power consumption, which, although important, isn't significant enough of an advantage when the numbers are this close.

Whether or not AMD will fail as a company remains to be seen. Maybe they will, maybe they won't. However, if you want to say that they do, then the supporting info that you give should be more accurate. -

army_ant7 blazorthonAs of right now, there is no retail Nvidia card that has better performance for the money (at least when overclocking is concerned) than some comparably performing AMD cards anymore. The GTX 670 ca't beat the Radeon 7950 in overclocking performance and it can't beat the 7950 in price either. The GTX 680 is no more advantageous against the Radeon 7970 and 7970 GHz Edition.Interesting. I didn't know that. :-) Is this generally true about the whole GCN lineup vs. the whole Keppler line up? I'm talking about overclocking performance of course since by default, the high-end Nvidia cards are more recommended, well at least the GTX 670. :-)Reply