Intel Comet Lake-S Arrives: More Cores, Higher Boosts and Power Draw, but Better Pricing

Kick the tires and light the TDP fires

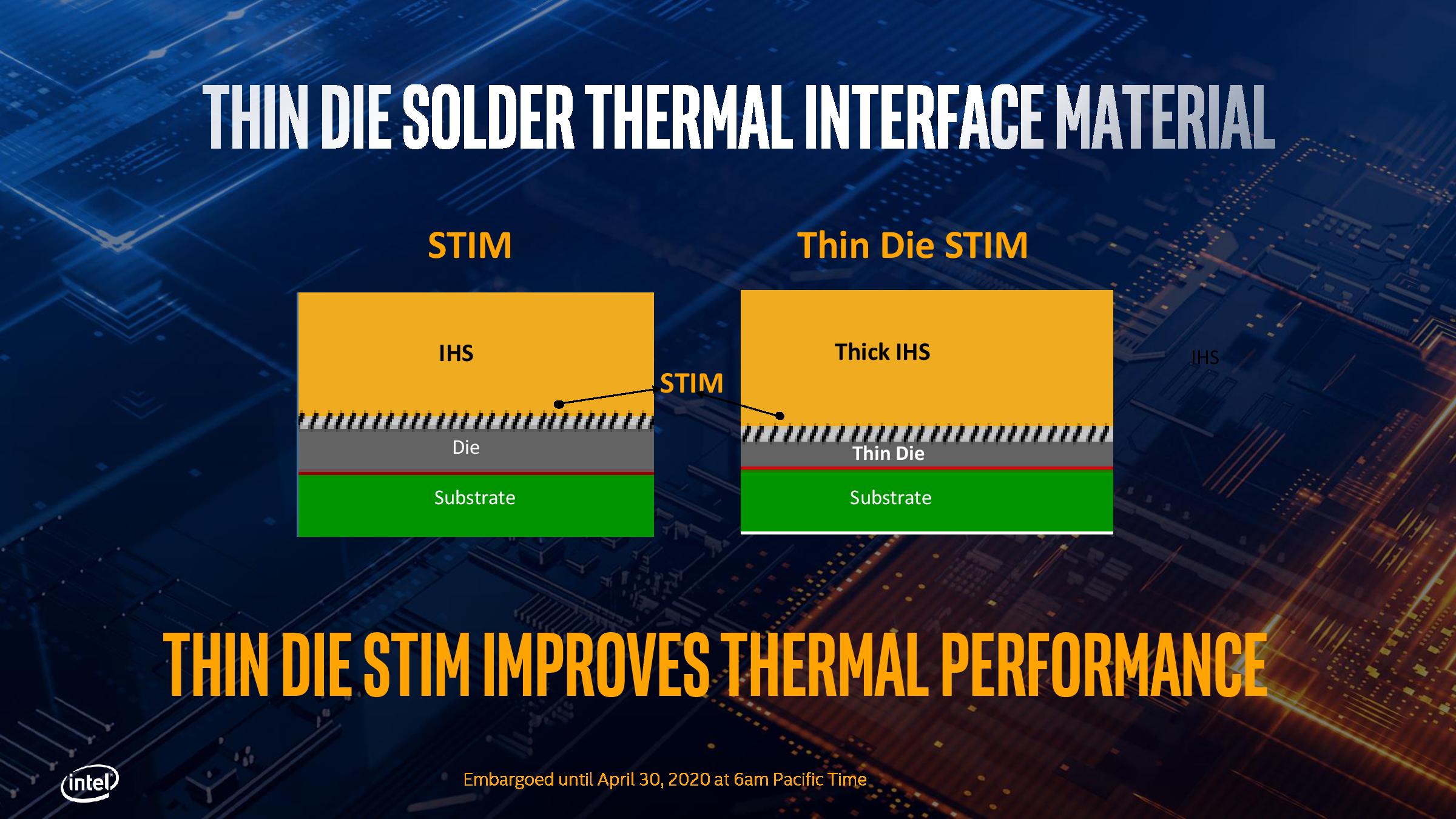

Thinner Die, Fatter IHS

Intel increased the power-to-performance ratio of its 14nm process by over 70% since the first iteration landed five years ago. Still, the company is surely reaching a diminishing point of returns as it enters the sixth or seventh round of optimizations. Recently, Intel has turned to dialing up the clocks and cores in tandem with peak power consumption. As you would imagine from the Core i9's 250W peak power draw at stock settings, boosting heat transfer efficiency to the die is becoming more important, especially if you're overclocking.

Intel moved from pTIM (polymer TIM - a.k.a. thermal grease) with its Coffee Lake K-series chips (and some standard models) to Solder TIM. STIM boosts heat transfer efficiency between the die and heat spreader, which lowers the operating temperature and often unlocks a higher overclocking ceiling. Lower temperatures also help during stock operation—they typically enable longer turbo boost durations and should lessen cooling requirements compared to the same chip with pTIM.

With up to ten cores now cooking away under the integrated heat spreader (IHS), Intel decided to further refine its approach by using a thinner die for the K-series Comet Lake CPUs. Intel says that it has reduced the processor die z-height (thickness) by 300 micro millimeters (from 800 to 500) to improve thermal transfer efficiency. Think of this technique as similar to lapping the die itself, thus shaving away a thin layer of silicon that rests between the heat-generating compute elements and the STIM.

Intel then pairs this approach with a thicker copper IHS. The company says copper is three times more efficient at transferring heat than silicon (which can actually act as an insulator), so more of the former is better for cooling than the latter. It also makes sense to thicken the IHS to assure adherence to existing socket z-height dimensions—that's part of what enables backward compatibility between LGA 115x coolers and the LGA 1200 interface.

Intel specified that it uses the 'die-thinning' technique on K-series models, but its messaging around the rest of the models is unclear. We do know the company still uses STIM on all of its K-Series processors, but some Core i5-10400 and 10400F chips will use either STIM or pTIM, which will vary based on the manufacturing location. We're following up to see if there is a discernible difference in packaging or part numbers.

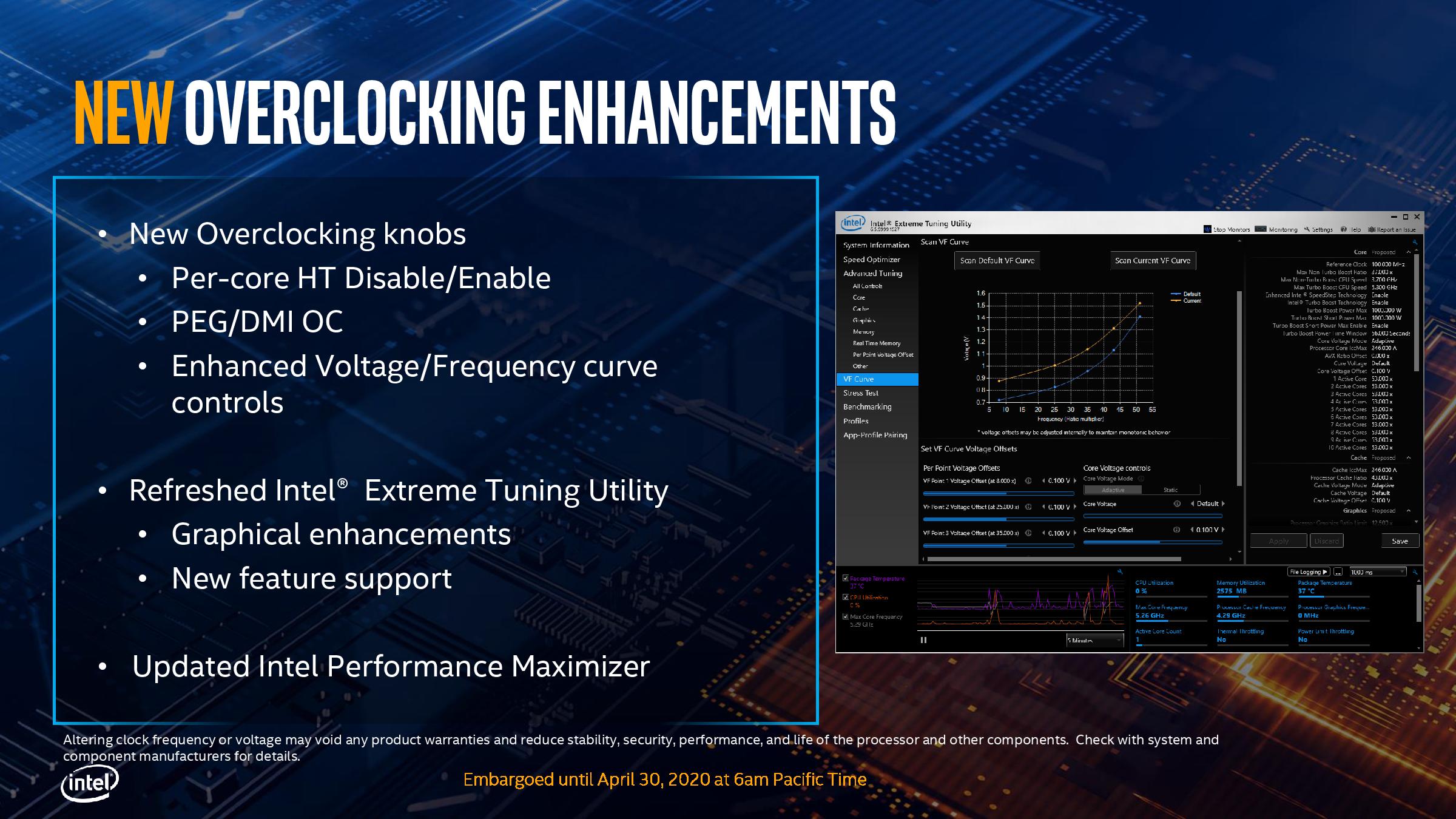

Intel holds the overclocking crown with its higher frequency ceilings, but the company continues to march forward with the development of its overclocking features and software.

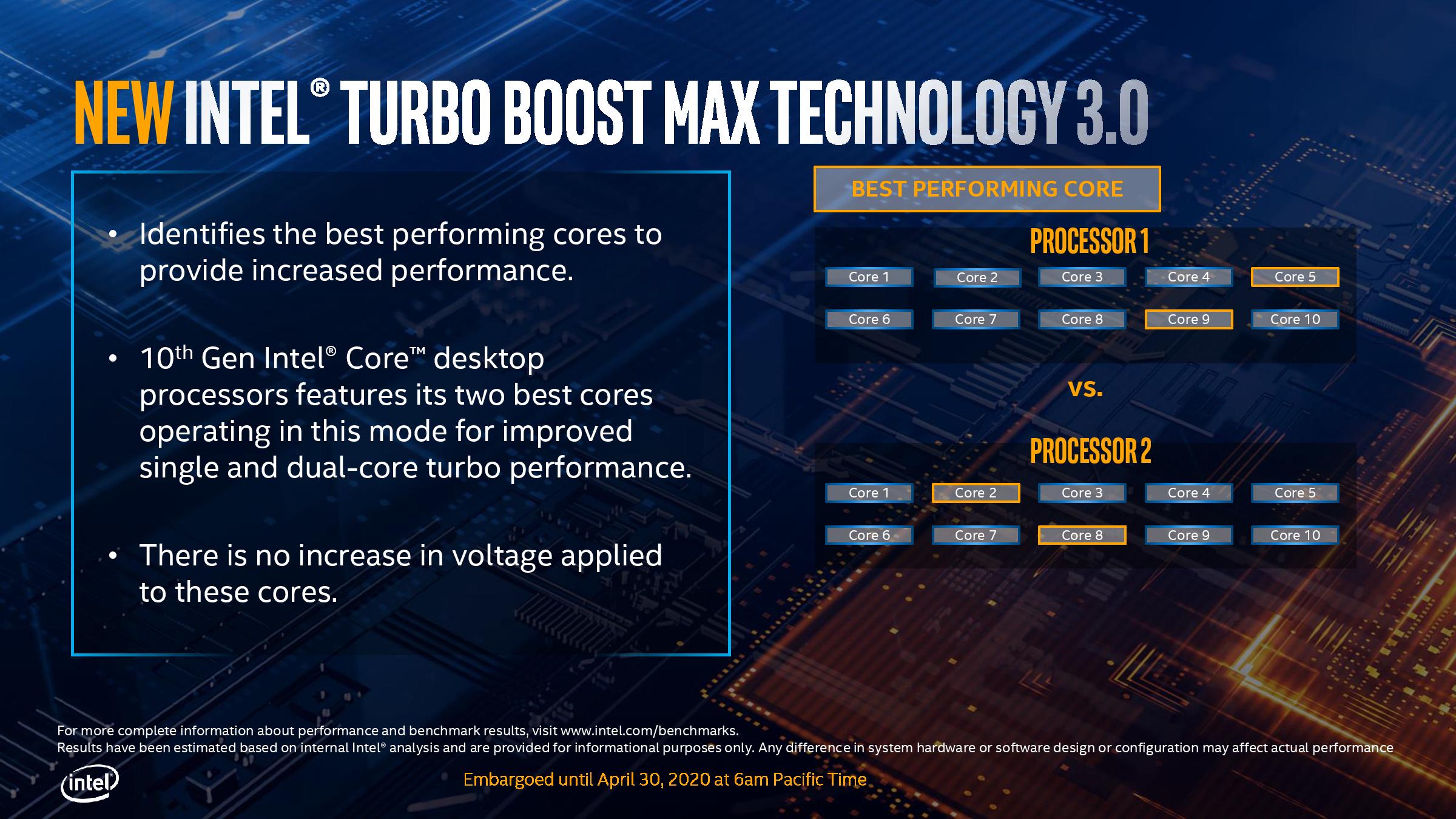

Comet Lake brings a completely new and somewhat unexpected feature: Now you can enable or disable hyper-threading (HT) on a per-core basis. This granular control could be useful for any number of scenarios, with the most obvious benefit being to reduce heat output, thus easing cooling requirements and enhancing turbo boost duration. Not to mention overclocking. You could also identify the 'weaker' cores in your system during overclocking and then selectively disable HT on those cores. Paired with targeted per-core overclocking, that could be a promising feature.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

However, disabling HT and pushing cores to higher frequencies might not be as productive if active threads aren't targeted to the faster cores. We're not sure if there is any co-operation between Intel's Turbo Boost 3.0 Max and the threading controls, but it seems doubtful. We do know that the HT feature can be triggered via Intel's eXtreme Tuning Utility (XTU), but it requires a reboot before threads are enabled/disabled.

Intel has also enabled fine-grained voltage/frequency (VF) curve adjustments in the XTU software, which allows you to adjust the various points in the curve. Some of these points on the curve were not previously available (including idle, which makes this feature appealing to undervolters). Intel won't describe the various points in detail because they are proprietary, but the company says you can see the changes in XTU. Intel also exposes the requisite VF curve and HT disable/enable hooks to external applications so that motherboard vendors can incorporate the feature into the BIOS. Third-party software applications can also use the feature.

Intel has also bulked up its PCIe overclocking functionality by creating a system that allows motherboard vendors to connect an external clock generator to the PCH, thus bypassing the fixed 100 MHz clock. Intel says this enables speeds (up to) ~104 to ~108 MHz, thus boosting PCIe and DMI throughput slightly. Intel positions this feature as designed for extreme/professional overclockers.

Comet Lake Security Mitigations

| Vulnerability | Coffee Lake Refresh/Whiskey Lake Mitigation | Comet Lake |

| Variant 1 (Spectre) | Operating System | Operating System |

| Variant 2 (Spectre) | Microcode + Operating System | Microcode + Operating System |

| Variant 3 (Meltdown) | In-Silicon | In-Silicon |

| Variant 3a | Microcode + Operating System | MCU |

| Variant 4 | Microcode + Operating System | Microcode + Operating System |

| L1TF (Foreshadow) | In-Silicon | In-Silicon |

| MFBDS/RIDL | - | In-Silicon |

| MSBDS/Fallout | - | In-Silicon |

| MLPDS | - | In-Silicon |

| MDSUM | - | In-Silicon |

Intel has suffered troubling performance losses as the company works to patch an onslaught of security vulnerabilities via software patches. Through slow integration of in-silicon fixes to the same problems, the company has reduced some of the performance overhead associated with the mitigations.

Intel shared Comet Lake's security mitigation matrix with us, and it appears that the new chips carry the same mitigations found with its latest revisions of its silicon, like the later Coffee Lake Refresh R0 die revisions we tested with the Core i9-9900KS.

As we can see in the table above, these mitigations do represent a step forward from the Coffee Lake Refresh chips at launch, but the R0 stepping die with the same level of mitigations first landed in our labs in October 2019. It's a bit surprising that Intel hasn't made more progress in the interim.

Current page: Die-Thinning, Overclocking, Dynamic Hyper-Threading, Mitigations

Prev Page Comet Lake-S Core i9, i7, i5 and i3 Next Page Intel Comet Lake Pentium Gold, Celeron, T-Series and Press Deck

Paul Alcorn is the Editor-in-Chief for Tom's Hardware US. He also writes news and reviews on CPUs, storage, and enterprise hardware.

-

tummybunny There seems to be a huge market that only buys Intel so we shouldn't feel sorry for them, but the comparisons between this and Zen 3 later on in the year will surely be devastating.Reply

Hopefully their supply issues are under control at least. -

alceryes Another review with some different details -Reply

https://www.anandtech.com/show/15758/intels-10th-gen-comet-lake-desktop

I don't think Intel is going to do too well with these. Requiring a new socket/chipset and releasing yet ANOTHER 14nm iteration chip is the wrong move when you're back on your heels after a very strong AMD release. -

TCA_ChinChin Better than before but the question is will it be enough for Zen 3? It'll probably convince some who are upgrading but anyone who has an AM4 chipset isn't going to be impressed. An i7 + new mobo = 400$ while just waiting for r5-4600 = 200$. Also overclocking is still locked to K series chips. The fact that Intel still has enough hubris to continue artificially segmenting products to this degree makes me sad.Reply -

Math Geek 250w for STOCK speeds!!! so prob breaking 300w with any type of overclocking. even the i3 was 182w peak at stock speeds. gonna need water-cooling for an i3 at this point.Reply

the fx series when it got this bad would only run on a select few motherboards that could handle the power draw. the intel fanboys threw around terms like space heater and many others to describe how crazy these power levels are. so new socket, expensive mobo to deliver the power, water cooling just to run at stock speeds and this is a big fat NOPE for me.

something tells me though that these new chips will get a good spin from the fan boys. i mean come on who doesn't need an extra space heater in the basement. that's a heck of a value feature from intel........blah blah blah -

jeremyj_83 These TDPs and PL2 numbers are insane. I'd be afraid to use a HSF that isn't a Noctua-D15 on even the T series CPUs.Reply -

Math Geek Replyjeremyj_83 said:These TDPs and PL2 numbers are insane. I'd be afraid to use a HSF that isn't a Noctua-D15 on even the T series CPUs.

i don't think i'd use air for anything above the i3 and then i'd consider a small AIO instead. once you approach 200w, then air just becomes too little too late. it'll throttle continuously and not perform at even stock levels on air. -

JarredWaltonGPU Reply

Intel is basically in the same place AMD was in with the Bulldozer series of CPUs: it has to release something new. Of course, Intel is also about 10X the size/profitability of AMD. And so we get a power increase, slightly higher performance, same old architecture with a few minor tweaks and two more cores.TCA_ChinChin said:Better than before but the question is will it be enough for Zen 3? It'll probably convince some who are upgrading but anyone who has an AM4 chipset isn't going to be impressed. An i7 + new mobo = 400$ while just waiting for r5-4600 = 200$. Also overclocking is still locked to K series chips. The fact that Intel still has enough hubris to continue artificially segmenting products to this degree makes me sad.

Anyway, yeah, I don't think Comet Lake is going to be a massive leap forward. It feels a lot like the Broadwell launch of 2015: too little, too late. What's really shocking is that Intel also has Rocket Lake coming presumably next year. That will also be 14nm+++ but will use the new Golden Cove cores, maybe integrated Xe Graphics as well? But still on 14nm, man... I don't know what to think.

AMD via TSMC has had equivalent process tech since mid-2019, and Apple launched 7nm chips via TSMC in 2018. And Intel still has plans for a 14nm desktop high performance part in 2021? I guess that's the chip that will really go away quickly, once we get Ice Lake or Tiger Lake or whatever (10nm) on desktop.

If AMD can make Zen 3 scale to higher frequencies (5GHz+) and improve IPC a bit more relative to Zen 2, it should finally manage to win every single meaningful comparison against Intel. Right now, AMD wins on cores and power and efficiency, it's close on IPC, but it clocks about 400-800MHz slower. All-core 5-5.1GHz overclocks on Intel are easy enough, and even 'stock' is 4.7GHz all-core. AMD all-core overclocks are more like 4.2-4.3GHz, and stock is only 100MHz lower. So, bump up those clocks for AMD and it can close the last remaining gap. -

JarredWaltonGPU Reply

A good air cooler technically shouldn't be much worse than a good AIO. One just makes it much easier to use a lot of fans and a big radiator. But dual 140mm fans on an air cooler should be pretty close to a 280mm radiator with an AIO -- and you don't have to deal with pumps. My biggest complaint about large air coolers is that they're a pain -- they block RAM slots, and some are so large that they won't fit on many boards.Math Geek said:i don't think i'd use air for anything above the i3 and then i'd consider a small AIO instead. once you approach 200w, then air just becomes too little too late. it'll throttle continuously and not perform at even stock levels on air.

Also, be wary of inexpensive AIOs. I've had multiple AIOs from Enermax fail, for example. Also a couple of previous gen Corsair models stopped cooling properly, and I don't know why -- H115i, and the pump and fans still work but it can't even cope with an i7-8700K (hits 90C+ at stock), never mind faster chips. NZXT is my go-to AIO now, but they're a lot more expensive than some of the other options. -

irish_adam Reply

From the reviews I have seen premium air coolers out perform almost all AIO liquid coolers bar 1 or 2, you'll need a custom loop to really get any better thermals.Math Geek said:i don't think i'd use air for anything above the i3 and then i'd consider a small AIO instead. once you approach 200w, then air just becomes too little too late. it'll throttle continuously and not perform at even stock levels on air. -

alceryes Reply

I disagree.irish_adam said:From the reviews I have seen premium air coolers out perform almost all AIO liquid coolers bar 1 or 2, you'll need a custom loop to really get any better thermals.

I've seen the reviews that don't show AIOs in a good light and some of them don't test properly (e.g. they don't turn the pump up to 'performance' - a few degrees temp gain with no audible increase if the case has ANY fans). I can only go by my direct experience and 'good' AIOs, like my H80i V2, are at least a match for the high end Noctuas. One of the problems is that more and more AIOs have entered the playing field in the last 3-5 years and, just like crappy air coolers, many of them are also crappy.