Enter the SlipChip: An SoC on the Road to DNA Data Storage

Imagine running "Surgeon Simulator Centennial Edition" out of a DNA-based storage medium.

A team of Chinese scientists from Southeast University developed a novel way to store information in DNA. In a research article published in Science, the team demonstrated a DNA synthesis and sequencing technique that uses a single electrode. This enabled the scientists to skip the longer and less stable chemical processes previously used for that purpose, simplifying and accelerating the process immensely.

Using DNA as a storage medium isn't new; Richard B. Feynman initially proposed it in 1959. What made DNA so attractive from the get-go is that it already functions as a storage device by itself - and one with an immense memory density. DNA can store information at a density of 455 ExaBytes per gram. Crudely put: an average 720g, 20 TB HDD comes in at a storage density of 0,027 TB per gram. So it becomes clear why it'd be interesting to pursue this road.

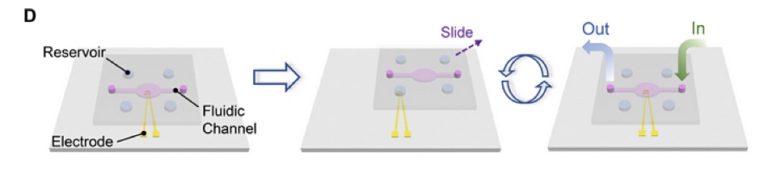

Schematic illustration of a data storage system based on DNA synthesis and sequencing on the same Au electrode.

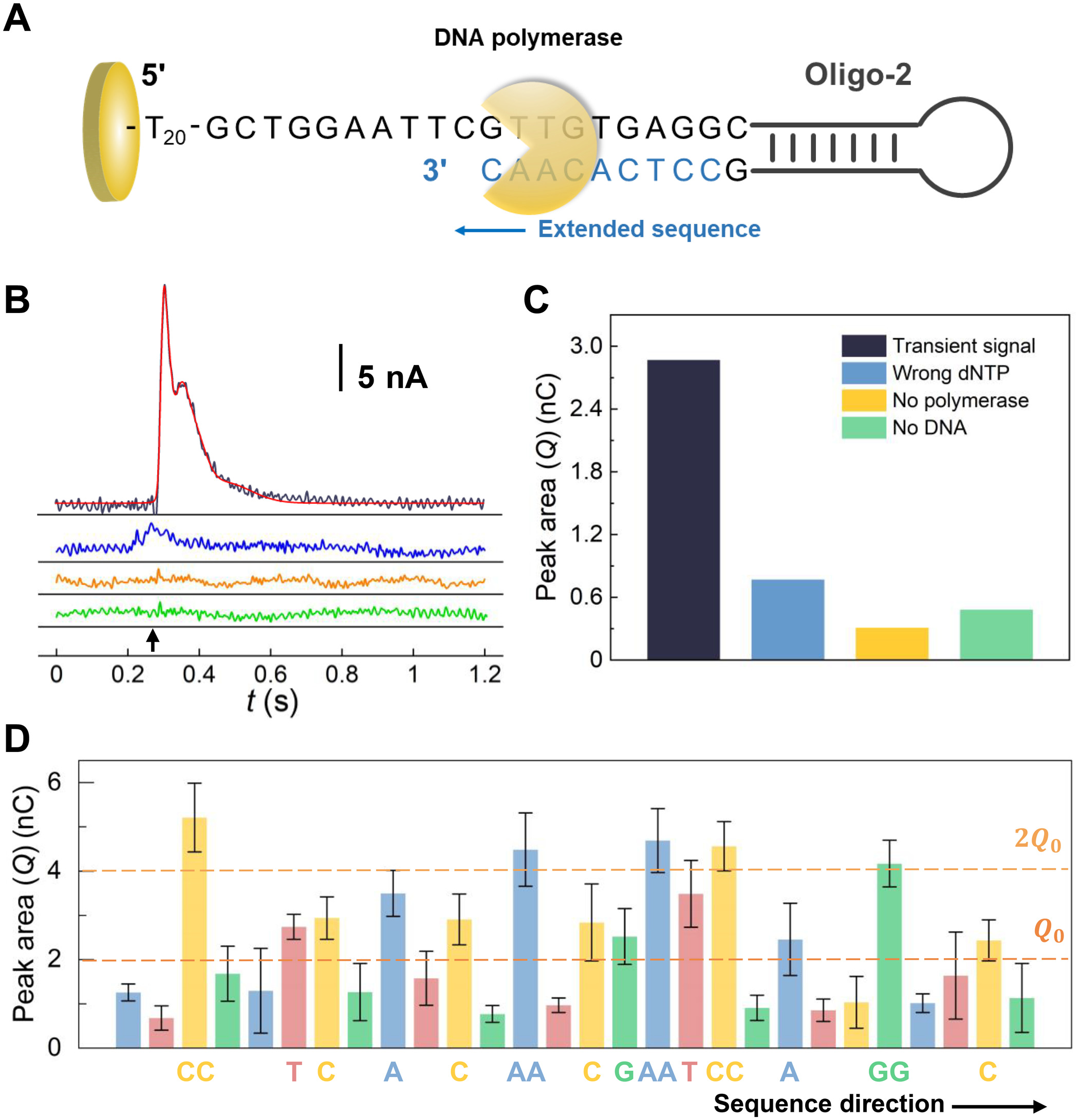

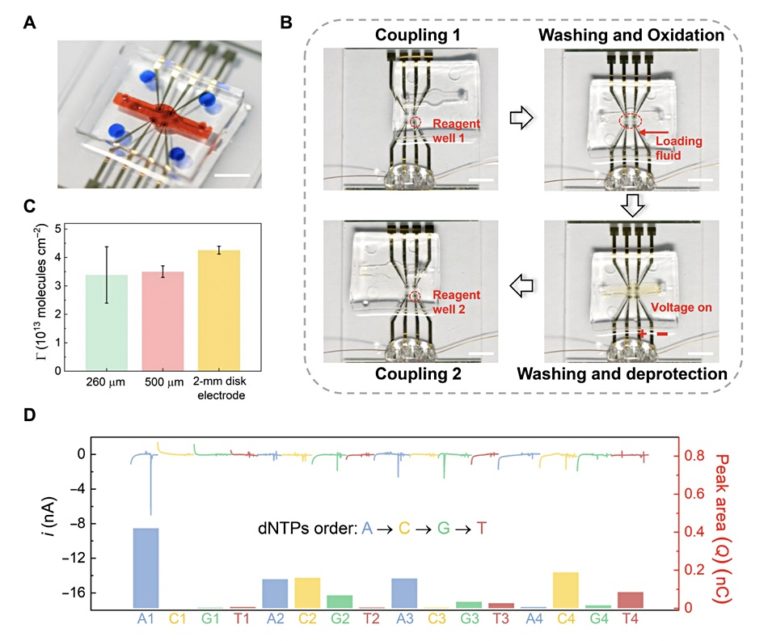

(A) Schematic showing the generation procedure for the DNA-based data storage. (B) Schematic of the electrochemically triggered phosphoramidite chemistry for the synthesis of DNA on the electrode. (I) A phosphoramidite nucleotide monomer with a dimethyltrityl (DMT) protecting group reacts with the free-hydroxyl group on the electrode/DNA molecule, forming a phosphite linkage. (II) The phosphite bond is oxidized by iodine to a more stable phosphate bond. (III) A positive potential is then applied to the electrode to generate protons. The acid-labile DMT protecting group on the nucleotide is removed to expose another free hydroxyl group for the addition of the next cycle. (C) Schematic of the DNA sequencing method on the same electrode based on charge redistribution in the sequencing-by-synthesis process. (IV) A known deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) and the DNA polymerase are added. Then, the polymerase binds to the template DNA, which is complementary with a primer DNA. (V) A proton is removed in the coupling reaction, and diffusion of the proton induces a charge redistribution and thus a transient current signal for base identification. (D) Schematic illustration of the principle of the SlipChip device for integrated DNA synthesis and sequencing. Four phosphoramidite nucleotide monomers for synthesis (or four dNTPs for sequencing) are preloaded in the reservoirs. A washing solution and other reagents are introduced using the fluidic channel. Liquid manipulation is accomplished by sliding the top plate.

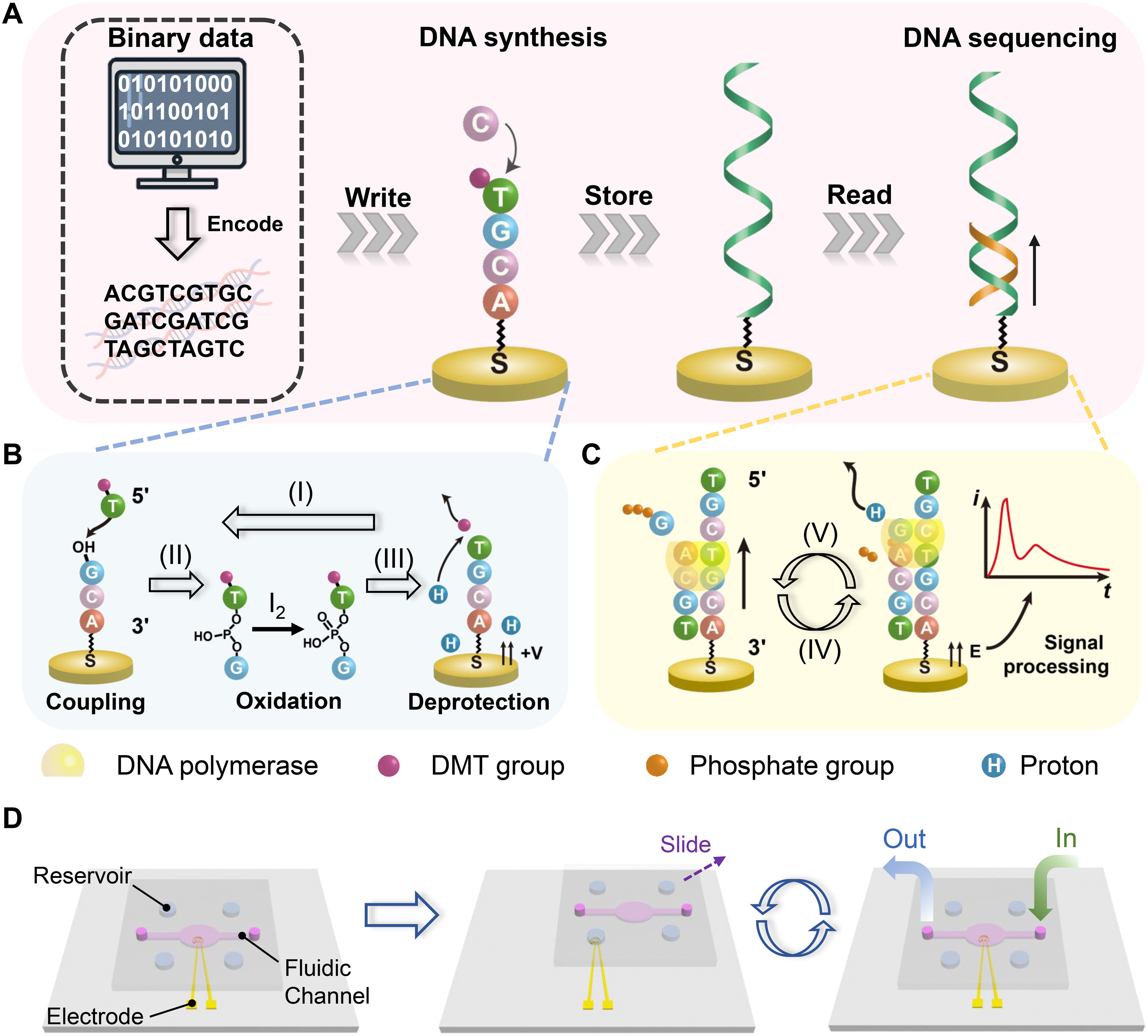

DNA sequencing on the electrode.

(A) Schematic illustration of the DNA sequencing-by-synthesis process for the self-priming Oligo-2. (B) Current as a function of time measured in the sequencing-by-synthesis process. Different reagents were introduced to electrodes having the self-priming Oligo-2 at the time marked using the black arrow, including polymerase and a complementary dNTP (black), polymerase and a noncomplementary dNTP (blue), and a complementary dNTP without polymerase (yellow), respectively. For the control experiment (green), there was no oligonucleotide on the Au electrode. A Gaussian fitting of the black curve was also shown (red). (C) Peak area/charge (Q) of the transient signals in response to the dNTP addition. The colors correspond to those of curves in (B). (D) Peak area/charge (Q) measured for sequencing of the Oligo-2. The sequencing was carried out by sequential introduction of different dNTPs in the order of A, T, C, and G to the electrode, while measuring the current. The number of dNTPs coupled for each time was determined on the basis of the magnitude of the peak area relative to Q0 and 2Q0, as indicated by the brown dash lines in the figure. Error bars represent the SD of five replicated measurements.

To achieve this feat, the scientists developed an entirely new way to handle DNA processing: they developed a "SlipChip," as they call it. Essentially, it's a small exchange chamber with microfluidic pathways, traps, and chambers that allow for controlled interactions between the various chemical compounds required for DNA synthesis and sequencing. The top plate can be restructured, when necessary, to move the DNA manipulation process to its next step.

It's here that the electrode bit of the technique enters: the SlipChip also encases a single gold electrode. It essentially defines two states: one state in the absence of DNA contact (0), and a second state which simply identifies the presence of DNA sequences (1) born from the latent electrical current that spikes during the process.

According to the researchers, this brings about much-needed simplification and increased security for the entire process. As they put it, current DNA storage methods "usually involve complicated liquid manipulations in each step and manual operations in between. Adding one phosphoramidite nucleotide monomer in the synthesis step generally requires the introduction of at least four kinds of liquid solutions, not to mention the sequencing step. These limit the scale-up capability of this technique and increase the error probability."

With the new technique, several roadblocks to DNA storage are now resolved. Equipment used in previous DNA processing methods (large and impractical) is no longer required; steps are simplified; and they can now be done without manual intervention, thus reducing errors. In addition, the entire process is now condensed into the venerable SlipChip - a DNA synthesis storage and retrieval System-On-a-Chip. It's the industrial revolution equivalent of DNA data storage research.

For the experiment, the researchers wrote the motto for the Southeastern University ("Rest in the highest excellence!") in binary data, which was encoded into the ATCG (quaternary) DNA base sequences. These are synthesized into DNA in the process. Sequencing (reading) the resulting DNA, the team first achieved a respectable 87.22% accuracy. Adding error correction capabilities via data redundancy in the encoding step unlocked the coveted 100% accuracy.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

If you're wondering how fast that process actually was, well, it really wasn't. The researchers managed to write and read at around 0.5 bytes/hour with a single electrode. That figure is ridiculously slow for the overall digital footprint of even a minute of our lives, let alone for meaningful storage space. However, the process is capable of scaling up, as currently designed. Increasing the number of electrodes to four, the researchers found it took about 14 hours to write and read 20 bytes of data, for an average of 1.43 bytes/hour — imperfect scaling on an already slow process. But there are scaling and improvement techniques to do from here as well - we must remember that Intel's Pentium started at 60 MHz back in 1993.

DNA-based storage is still a long way off in any significant capacity. Significant speed improvements are still required, but that is customary in every field. If the Cambrian explosion of DNA storage is yet to come, this is one more important step on that journey.

Francisco Pires is a freelance news writer for Tom's Hardware with a soft side for quantum computing.