Intel Core i7-3960X (Sandy Bridge-E) And X79 Platform Preview

It's always interesting to get hands-on time with unreleased hardware. We were recently able to benchmark Intel's upcoming Core i7-3960X CPU, comparing it to Core i7-990X, Core i7-2600K, and AMD's Phenom II X6. Will you be in line for Sandy Bridge-E?

Sandy Bridge-E: Combining Two Pretty Popular Worlds

There’s an amazing amount of conflicting information about Sandy Bridge-E online, and it’s all attributable to Intel. The Sandy Bridge-E/X79 combination was originally planned to include on-processor PCI Express 3.0 support. It was supposed to enable 14 SATA ports, 10 of which were 6 Gb/s-capable and ready to accommodate SAS drives. There was even an additional four-lane link between the CPU and PCH dedicated to augmenting storage performance.

As it stands right now, though, all of those plans have fallen through. That’s not to say we’re expecting Sandy Bridge-E to be a disappointment. Its feature set still promises to give enthusiasts more performance.

Update: After this piece went up, several credible sources confirmed that Sandy Bridge-E's PCIe actually is 8 GT/s-capable; Intel just hasn't gone through the validation process yet. From what I'm told, there will be a second batch of processors in '12 that follows what we see at launch, and those will receive the official third-gen blessing. Until then, it'll have to be up to motherboard vendors to claim (or not) PCIe 3.0 compliance.

With all of that said, the platform in this story was still not set up for PCIe 3.0.

So, What’s New?

All three SKUs are 130 W parts, staying true to the top thermal ceiling we’ve seen since the days of Pentium D. Within that envelope, Intel is able to turn knobs and dials to affect performance in different ways.

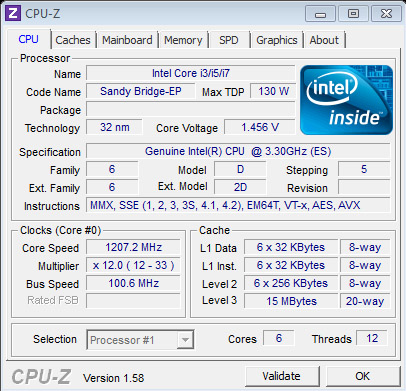

For instance, the flagship Core i7-3960X should ship with a 3.3 GHz base clock that spins up to 3.9 GHz with one or two cores active. It’s slated to include six cores, Hyper-Threading-capable, meaning it's equipped to handle 12 threads simultaneously. Core i7-3930K will step down to 3.2 GHz with a maximum Turbo Boost frequency of 3.8 GHz. And the Core i7-3820 is expected to feature a more aggressive 3.6 GHz base clock able to reach 3.9 GHz with Turbo Boost. It’ll only sport a 4C/8T arrangement, though.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

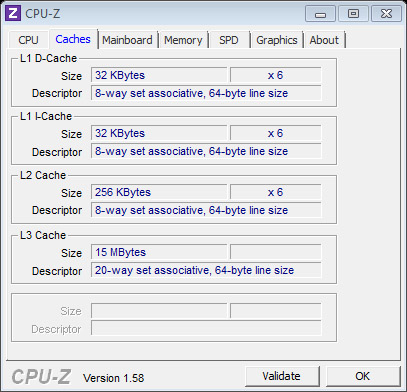

Sandy Bridge-E carries over the per-core 32 KB L1 data/instruction and 256 KB L2 caches. The shared last-level cache is a bit different, though. Sandy Bridge employed one 2 MB slice of L3 cache per core, totaling 8 MB at most. This is seemingly increased to 2.5 MB per core and still granular down to 512 KB, enabling the 12 and 10 MB caches expected from the -3930K and 3820, respectively.

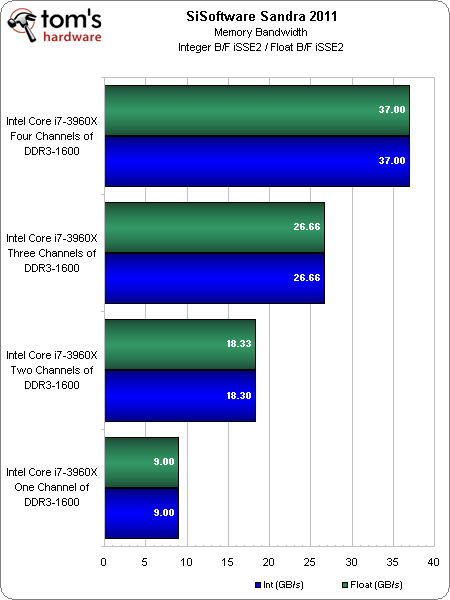

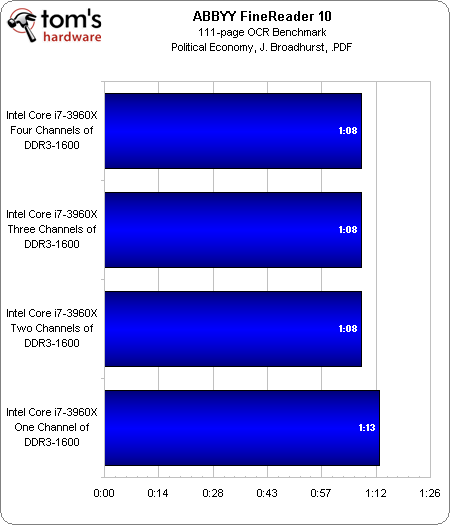

Nehalem’s triple-channel DDR3-1066 memory controller gives way to a quadruple-channel controller able to support DDR3-1600 data rates. The potential increase in memory bandwidth, from 25.6 GB/s to 51.2 GB/s, is massive. But don’t expect to see a corresponding increase in benchmark performance on the desktop. As it was, the Nehalem architecture was not bandwidth-starved on X58 (we even proved it in Core i7 Memory Scaling: From DDR3-800 to DDR3-1600). And Sandy Bridge has no problem flying right past Bloomfield with only a dual-channel DDR3-1333 memory controller.

As with desktop Sandy Bridge, Sandy Bridge-E handles PCI Express control. Instead of a paltry 16 lanes of second-gen connectivity, though, we get 40 lanes. Those lanes can be divided up into two x16 links and one x8 link, one x16 link and three x8 links, or one x16 link, two x8 links, and two x4 links. This would be great news for gamers, except that we already know you can take a P67- or Z68-based board, add an NF200 controller, and still get exceptional performance from up to three graphics cards. More than likely, all of that PCI Express will become a bigger boon to servers full of GPU compute boards, add-in RAID controllers, and 10 Gb Ethernet cards.

What happened with PCI Express 3.0 support? Obviously, nobody at Intel was going to comment on this piece, so it’s hard to say. What we do know is that PCIe 3.0 was planned, and the cards needed for validation didn't arrive in time, though Intel might end up marketing "8 GT/s support," rather than run afoul of any specification deviation. For now, the board vendors we've spoken to are claiming PCIe 2.0-only.

Sandy Bridge-E is still manufactured on Intel’s 32 nm node, and I’m not yet sure how large the die is, or how many transistors it includes. What we do know is that it doesn’t have an on-die graphics processor built in, which also means the Quick Sync functionality we came to love from Sandy Bridge is not available here.

Moreover, we’re still dealing with Intel’s Turbo Boost 2.0 technology, which you can learn more about in my original Sandy Bridge coverage. Sandy Bridge-E incorporates AVX support, and what we can only describe as a vastly improved implementation of AES-NI (more on that in the benchmarks.

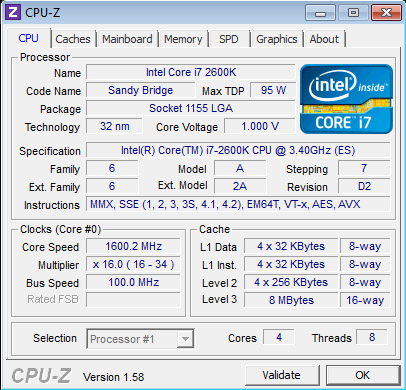

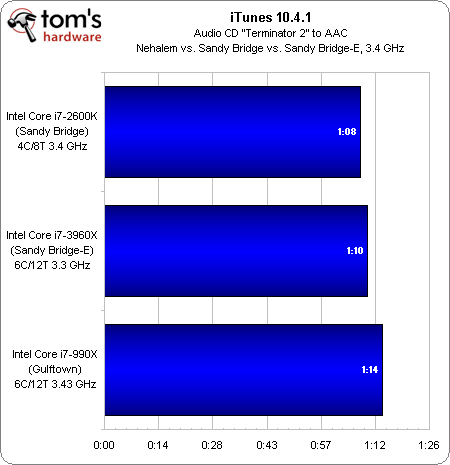

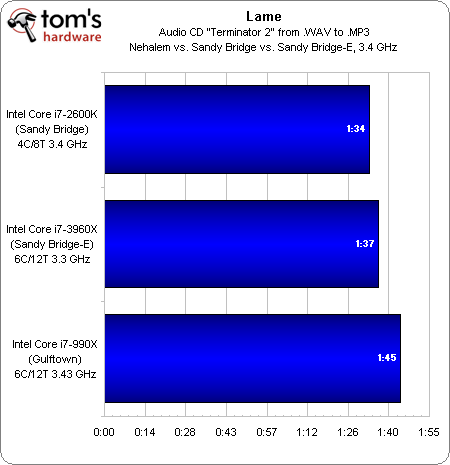

A quick look at per-clock performance (achieved by getting Gulftown, Sandy Bridge, and Sandy Bridge-E running at 3.4 GHz without Turbo Boost turned on) reveals that Core i7-3960X is actually a little slower than Core i7-2600K. Fortunately, by giving the fastest Sandy Bridge-E chip a 3.9 GHz Turbo Boost ceiling, it’s able to at least match Corei7-2600K’s 3.8 GHz in single-threaded apps.

Current page: Sandy Bridge-E: Combining Two Pretty Popular Worlds

Prev Page Sandy Bridge-E And X79 Are Almost Ready Next Page X79 Express And Another New Processor Interface-

tri force "AMD FX-8150 (Zambezi) 3.6 G...Alright, that's just mean"Reply

I felt really happy for a second :( -

for the price, the 8150 at 250 dollars will smoke intel out the water. IF you really want to go dolla per dollar , a dual socket amd opteron 6220 system will severely outperform the intel i73960 for alot cheaper. Thats 16 x 3.5 ghz turbo bulldozer cores against 6 3.3 ghz sandy bridge cores. hmmReply

-

jprahman I was really looking forward to Sandy Bridge-E, but it looks like a mixed bag from the review. The lack of USB 3 and especially PCI-E 3 was really disappointing, especially for an enthusiast class processor and chipset. The dearth of SATA ports was pretty surprising too, everything up to this review had indicated far more.Reply

The extra performance you can get looks pretty nice for stuff like transcoding, but the performance in the majority of applications doesn't justify the extra cost for the i7-3960. I'd rather get a i7-2600K or i5-2500K... or wait for Bulldozer to see how it performs relative to an i5-2500k or i7-2600k.

To be honest, this review almost comes off like an attempt to chill any interest high-end enthusiasts might have for Bulldozer. -

hmp_goose I predict a "meh" from enthusiast … And a far number of LGA1366 drivers looking for a price cut. ;-)Reply -

Wamphryi I just got an i7 2600 K and like a previous writer commented I have no regrets either. The 2600 K is such good bang for buck and lots of people seem to be snapping them up.Reply -

Tamz_msc I hope Bulldozer is more interesting than this. I honestly dont see many enthusiasts investing in this - they're better off waiting for Ivy Bridge.Reply -

raclimja what a massive disappointment, i was hoping for big performance improvement from intelReply

i guess i will just stick with my i5 2500k and upgrade my aging HD 4870 x2 to something like GTX 680 or HD 7900 -

dalauder You say the i7-3820 will be a tough sell, but maybe, like the i7-2600, it will be an excellent non-overclocked part for OEM machines. For that purpose, I think a machine that can run DDR3 1600MHz at without overclocking is a reasonable upgrade over the i7-2600.Reply

There is a market for people who want top-end gaming machines but never want to look inside other than to add more graphics. Based off of Cyberpower, IBuyPower, Alienware, etc.--I bet that market is at least as big as enthusiasts that hand pick their parts.