OpenCL In Action: Post-Processing Apps, Accelerated

We've been bugging AMD for years now, literally: show us what GPU-accelerated software can do. Finally, the company is ready to put us in touch with ISVs in nine different segments to demonstrate how its hardware can benefit optimized applications.

What Does Heterogeneous Computing Really Promise?

No one is ready to declare the age of CPUs over. After all, companies like Xilinx still sell application-specific programmable logic devices that are far less functionally integrated and multi-purpose than modern central processing units. Sometimes, simpler is more effective. It’s likely that specialized processors will continue to enjoy success in certain markets segments, especially where lots of performance is the top concern. In an increasingly diverse range of mainstream environments, though, we expect that heterogeneous computing—having many types of computational resources packed onto a single, integrated device—will continue to become more popular. And as manufacturing devices, these devices will get more complex, too.

The logical endgame of heterogeneous computing is a system-on-a-chip (SoC), wherein all (or at least many) major circuit systems are integrated into one package. As an example, AMD’s Geode chips (currently powering the One Laptop Per Child project) have evolved from 1990s-era SoC designs. While many SoC products still lack the horsepower to fuel a modern, mainstream desktop PC, both AMD and Intel sell architectures that combine CPU cores, graphics resources, and memory control. These accelerated processing units (APUs), as AMD calls them, meet and even exceed the performance levels expected from typical productivity-oriented workstations. Most notably, they complement familiar processor designs with many, many ALUs typically used to accelerate 3D graphics. These programmable resources don't have to be used for gaming, though. Many other workloads are very parallel by nature, and throwing an APU with hundreds of cores at them (rather than just a CPU with two or four cores) launches an interesting debate about the potential of software optimized for highly-integrated SoCs.

Historically, on-board graphics solutions were enabled by logic in the chipset’s northbridge. Hamstrung by severe bottlenecks and latencies, at a certain point it simply became more difficult to scale up performance using platform components so far away from each other. As a result, we've seen that functionality migrate north into the CPU, creating a new breed of products able to not only offer significantly better gaming performance, but also to tackle more general-purpose tasks that leverage the hybrid nature of SoCs with CPU and GPU functionality.

For AMD, this marks the long-sought culmination of the company’s Fusion initiative, which was presumably the driver behind AMD’s 2006 acquisition of ATI Technologies. AMD saw the potential for its CPUs and ATI's graphics technology to supplant pure CPUs in an ever-increasing share of the market, and the company was determined to be in the vanguard of that transition. Intel, of course, employs its own in-house graphics technology, but to a different end. Decidedly, its emphasis has been more focused on its processing cores and less on graphics technology.

Early 2011 witnessed the first family of AMD C- and E-series APUs arrive, manufactured on a 40 nm process. The use of integration enabled low-power 9 and 18 W models that went into ultra-portable notebooks. Today, we have the Llano-based A-series APU family. The use of 32 nm manufacturing makes it possible to cram in enough resources for a true desktop-class architecture at a value-oriented price point.

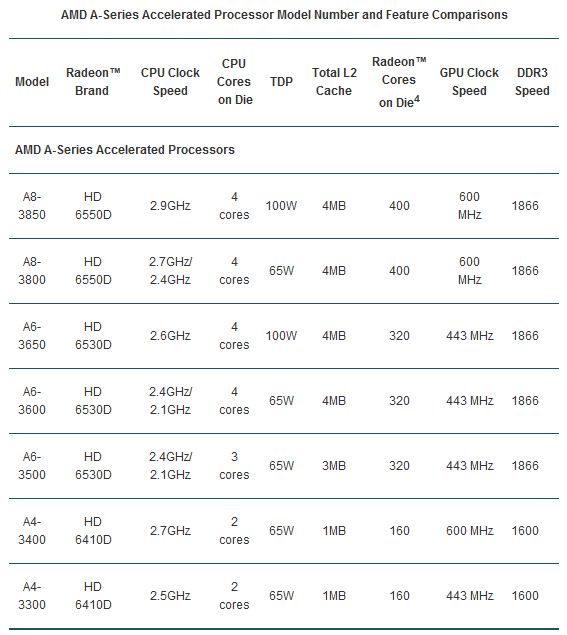

While there are a variety of specifications in play here, perhaps the biggest differentiator among the models listed below is their respective graphics engines. The A8 employs a configuration that AMD refers to as Radeon HD 6550D. It consists of 400 stream processors, Radeon cores, or shaders, whichever name you like to use. The A6 steps down to the Radeon HD 6530, boasting 320 stream processors. And the A4 scales back to a Radeon HD 6410D with 160 stream processors.

We've already run sub-$200 CPUs and APUs through a number of our favorite game benchmarks, so we know how the latest chips soar or sink in modern titles. Now we want to have a look at some of the other ways enthusiasts are able to take advantage of compute resources, though, using workloads that tax conventional CPU cores and the programmable processors found in graphics-oriented products.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

In this initial installment of what will be a nine-part series, we’re putting video post-processing under the microscope. Back in the day, this would have been a time-consuming usage model, even with a multi-core CPU under the hood. Because it's a largely parallel workload, though, accelerating it with the many cores of a graphics processor has become a great way to increase productivity and improve performance.

We enlisted AMD's help in putting this series together, so we're going to focus on the company's hardware to create some pretty basic comparisons. How does a CPU on its own work in OpenCL-enabled software? How about one of the Llano-based APUs on its own? Then we'll match the cheaper APUs and pricier CPUs up to a couple of different discrete cards to chart how performance scales up and down across each configuration.

Current page: What Does Heterogeneous Computing Really Promise?

Next Page DirectCompute And OpenCL: The Not-So-Secret Sauces-

bit_user amuffinWill there be an open cl vs cuda article comeing out anytime soon?At the core, they are very similar. I'm sure that Nvidia's toolchain for CUDA and OpenCL share a common backend, at least. Any differences between versions of an app coded for CUDA vs OpenCL will have a lot more to do with the amount of effort spent by its developers optimizing it.Reply

-

bit_user Fun fact: President of Khronos (the industry consortium behind OpenCL, OpenGL, etc.) & chair of its OpenCL working group is a Nvidia VP.Reply

Here's a document paralleling the similarities between CUDA and OpenCL (it's an OpenCL Jump Start Guide for existing CUDA developers):

NVIDIA OpenCL JumpStart Guide

I think they tried to make sure that OpenCL would fit their existing technologies, in order to give them an edge on delivering better support, sooner. -

deanjo bit_userI think they tried to make sure that OpenCL would fit their existing technologies, in order to give them an edge on delivering better support, sooner.Reply

Well nvidia did work very closely with Apple during the development of openCL. -

nevertell At last, an article to point to for people who love shoving a gtx 580 in the same box with a celeron.Reply -

JPForums In regards to testing the APU w/o discrete GPU you wrote:Reply

However, the performance chart tells the second half of the story. Pushing CPU usage down is great at 480p, where host processing and graphics working together manage real-time rendering of six effects. But at 1080p, the two subsystems are collaboratively stuck at 29% of real-time. That's less than half of what the Radeon HD 5870 was able to do matched up to AMD's APU. For serious compute workloads, the sheer complexity of a discrete GPU is undeniably superior.

While the discrete GPU is superior, the architecture isn't all that different. I suspect, the larger issue in regards to performance was stated in the interview earlier:

TH: Specifically, what aspects of your software wouldn’t be possible without GPU-based acceleration?

NB: ...you are also solving a bandwidth bottleneck problem. ... It’s a very memory- or bandwidth-intensive problem to even a larger degree than it is a compute-bound problem. ... It’s almost an order of magnitude difference between the memory bandwidth on these two devices.

APUs may be bottlenecked simply because they have to share CPU level memory bandwidth.

While the APU memory bandwidth will never approach a discrete card, I am curious to see whether overclocking memory to an APU will make a noticeable difference in performance. Intuition says that it will never approach a discrete card and given the low end compute performance, it may not make a difference at all. However, it would help to characterize the APUs performance balance a little better. I.E. Does it make sense to push more GPU muscle on an APU, or is the GPU portion constrained by the memory bandwidth?

In any case, this is a great article. I look forward to the rest of the series. -

What about power consumption? It's fine if we can lower CPU load, but not that much if the total power consumption increase.Reply