Ultrabook: Behind How Intel is Remaking Mobile Computing

We recently had the opportunity to sit down with some of Intel's high-level execs responsible for the Ultrabook initiative to talk about its inception, to track its progress over a few generations, and to get an idea of where Ultrabooks are going.

The Ultrabook Idea's Thin Beginnings

In 2006, even while laptop sales were tracking on over a decade of growth, Intel knew it had a problem. The level of innovation in notebooks had fallen to nearly stagnant (perhaps ironically, what we're now saying of the desktop). There were bulky mobile workstations. There were ho-hum thin-and-lights. Efforts to craft svelte, exciting mobile platforms had been gathering headlines for years...but not many sales.

Battery life was often insufficient for airplane travel. Processors were underpowered. Designs felt cheap and gimmicky. Really, nothing had shaken up the mobile space since Centrino’s arrival in 2003—a $150 million marketing effort that had ultimately succeeded in eliminating the connectivity wire from laptops.

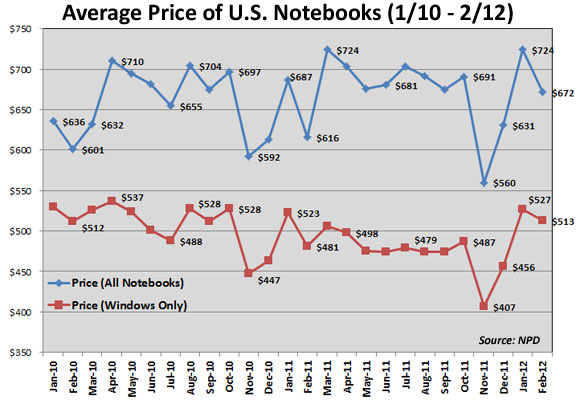

While notebook sales were great (2007 would be the first year that notebook sales surpassed desktops), the space had become mind-numbingly commoditized, and that meant the only way to increase share was to embark in a rock bottom price war. NPD numbers show the average selling price of Windows notebooks bottoming out at just over $400 in November 2011. Nobody can make money at those levels, Intel included.

Naturally, Intel had a plan. The lasting lesson of Transmeta was that there was a place and a need in the world for low-power processors and the form factors they could enable. In fact, Intel’s first ultra-low voltage (at 1.35 V) chip was a Celeron part in February of 2000. So by 2006, the idea of tailoring silicon to meet form factor needs was far from new. However, old-school Intel was all about saying, “Hey, everybody, look at our new chip. Here are some things you can do with it.” That mindset was vanishing by 2006. The company learned its lesson from Centrino: it’s not the chips that matter; it’s what you do with them.

Said differently, mobility was not about speeds and feeds. It was about experiences. Interestingly, this was (and still is) AMD’s top marketing sentiment for years and years. Intel had taken the time to study how people go about their mobile computing and the sorts of experiences they wanted, and from that emerged what would eventually be the company’s long-term Ultrabook strategy.

Intel was beginning to understand style. Notebooks needed to get much thinner and lighter than they already were. People were willing to trade a few inches of screen size for superior convenience. Processing and storage had to be on par with desktop-class hardware, but everyone wanted battery life to improve considerably.

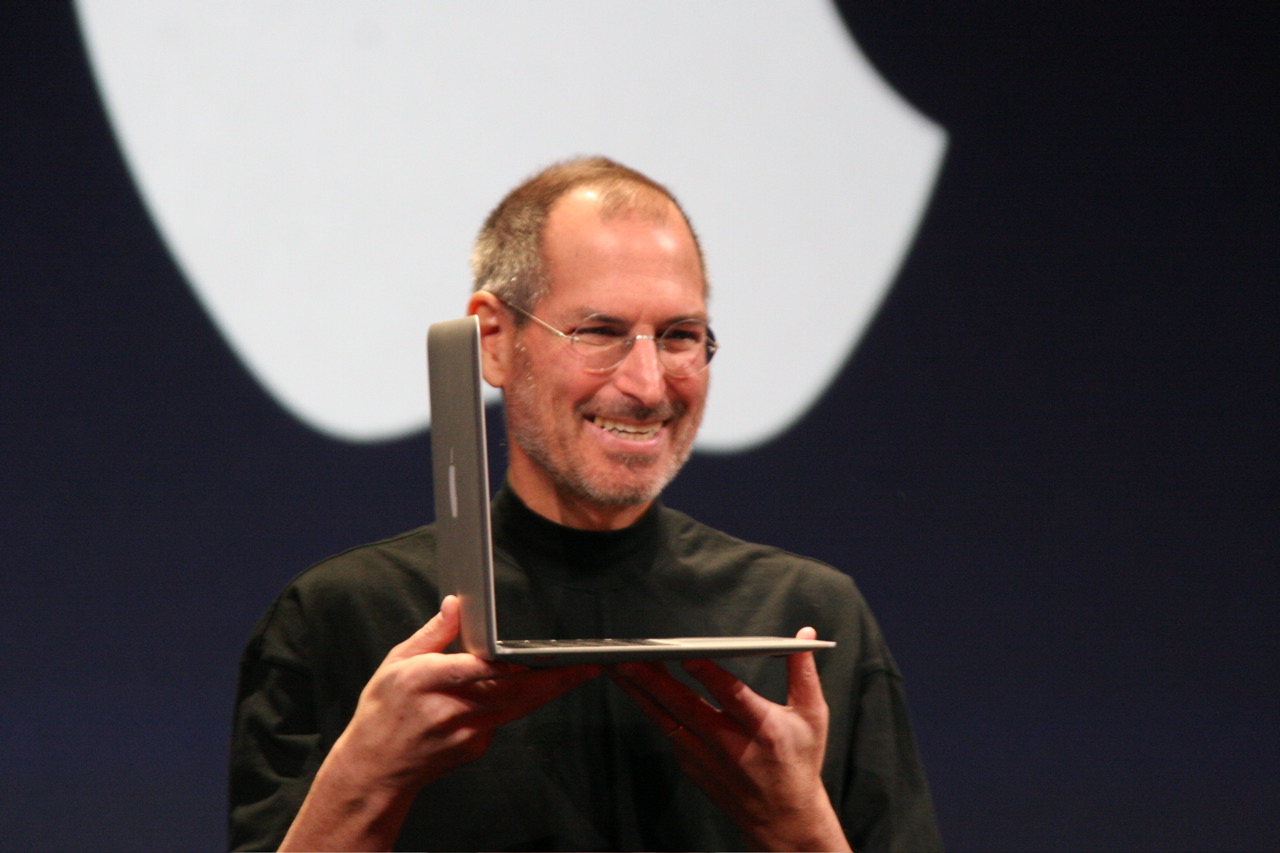

Intel wasn’t shy about discussing these ideas in the OEM world, and everyone listened. But it was Apple and Apple alone that seemed to grasp the real message. When Steve Jobs showed the first MacBook Air in the beginning of 2008, it ran on an Intel Core 2 Duo “Merom” processor and was billed as the thinnest notebook ever.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

It was a small beginning.

-

techtalk I am just half way through the article. I am compelled to comment here. "What an Article" Amazingly well written, superb flow and great content.Reply -

outlw6669 Reply11271822 said:The battery always comes out first.

Words to live by.

RIP brave little Ultrabook. -

nibir2011 ReplyUltrabook aims to make its platform so compelling that, frankly, you’d be a fool to consider an under-performing, over-priced, feature-limited high-end tablet.

It will be only possible if Intel and AMD goes hand in hand. Mobile sector is so lucrative to OEM that eventually they will go there until there is a great product. If intel only thinks about their own business then it will be like what microsoft did to desktop. No software developers do not want to make consumer application, as app developing is business friendly.

It has to be a joint collaboration. -

nibir2011 ReplyUltrabook aims to make its platform so compelling that, frankly, you’d be a fool to consider an under-performing, over-priced, feature-limited high-end tablet.

It will be only possible if Intel and AMD goes hand in hand. Mobile sector is so lucrative to OEM that eventually they will go there until there is a great product. If intel only thinks about their own business then it will be like what microsoft did to desktop. No software developers do not want to make consumer application, as app developing is business friendly.

It has to be a joint collaboration. -

kartu Huge, fictional article on what is supposed to be a tech site.Reply

Everyone has a notebook. Most of them are more than fast enough.

Now what can a company that excels only at CPUs do about that?

It sure takes a genius to notice that people like lighter thinner thingies, right.

I'm sure Steve Jobbs (I guess that's The Genius to the article's author) absolutely had to take part in this astonishingly far sighted decision to go lighter and thiner, it is soo far sighted, nobody else could have imagined that.

People prefer thinner and lighter, cooler looking things... What a frucking surprise... -

williamvw Reply11274396 said:Huge, fictional article on what is supposed to be a tech site.

Fictional. I'm not sure that word means what you think it means.

11274396 said:Everyone has a notebook. Most of them are more than fast enough. Now what can a company that excels only at CPUs do about that?

That is an excellent question. You may wish to review pages 1 through 6 for answers. Pages 10 through 13 aren't bad, either. None of the content in them is fictitious, in case you remain unsure.

11274396 said:People prefer thinner and lighter, cooler looking things... What a frucking surprise...

Thank you for your input. Your skepticism is even more warranted than it is well-stated. Of course, just because people want things doesn't mean that those things actually exist. Or are affordable. Or can be serviced. I mean, at least that's the case in the real world. In fictional scenarios, where the Tooth Fairy delivers ultralight notebooks from the future, tiny companies can move product ecosystems with the same ability and effectiveness as large ones, and unicorns soar majestically through pink and purple treetops, I suppose anything is possible. In the real world, though, this article describes how things actually get done.

-

superduper Although a well written article, I still have reservations regarding some of the context:Reply

The battery life "ballooning" had very little to do with Ultrabooks but rather silicon that was more frugal, particularly at idle and the density of battery packs. Your average Ultrabook often sacrifices Li-Polymer battery capacity to remain thin and svelte (MBA an exception). As a result, the 35W notebook with the bigger battery will get better battery life than the 17W ULV (vast majority of computing is spent at idle).

The facial and speech recognition software seems very nifty, but it's still not something that's an Ultrabook specialty. The software is available to tablets and smartphones as well (the Moto X uses a specialized core specifically to handle the speech recognition).

I'm far more interested in what Intel is looking to offer in 2015 for the Ultrabook platform than I am about the rather weak software additions that don't differentiate it. What is Intel going to offer me in exchange for the extra $200-$300 dollars out of my pocket for an Ultrabook? What am I getting beside a thinner chassis to warrant that much cash? In some ways, to me it seems like Intel and its OEMs have become victims of their own success. The Ultrabook is there to revive some lost sales to the mobile market, but outside of a higher price tag and a dedicated keyboard, I don't see what the bonuses are. -

williamvw Reply11275162 said:Although a well written article, I still have reservations regarding some of the context:

The battery life "ballooning" had very little to do with Ultrabooks but rather silicon that was more frugal, particularly at idle and the density of battery packs. Your average Ultrabook often sacrifices Li-Polymer battery capacity to remain thin and svelte (MBA an exception). As a result, the 35W notebook with the bigger battery will get better battery life than the 17W ULV (vast majority of computing is spent at idle).

The facial and speech recognition software seems very nifty, but it's still not something that's an Ultrabook specialty. The software is available to tablets and smartphones as well (the Moto X uses a specialized core specifically to handle the speech recognition).

I'm far more interested in what Intel is looking to offer in 2015 for the Ultrabook platform than I am about the rather weak software additions that don't differentiate it. What is Intel going to offer me in exchange for the extra $200-$300 dollars out of my pocket for an Ultrabook? What am I getting beside a thinner chassis to warrant that much cash? In some ways, to me it seems like Intel and its OEMs have become victims of their own success. The Ultrabook is there to revive some lost sales to the mobile market, but outside of a higher price tag and a dedicated keyboard, I don't see what the bonuses are.

Excellent points, and I agree with all of them. You are absolutely correct about the battery issue. Intel has no influence that I know of over Li-Ion battery efficiency; it can only try to reduce the platform's drain on the battery that's there. That was the company's challenge: how to get every component to consume less power. Obviously, some have more leeway than others.

I also share your curiosity about 2015, as I indicated in the conclusion. It might be fair to say that if Centrino's mission was to cut the Ethernet cord, Ultrabook's (at least initial) mission is to cut the power cord. The thinner and lighter business just goes along for the ride.

To be totally honest, 2012 Ultrabooks were not enough to interest me. It wasn't different enough from what I already owned. But you have to start somewhere and implement change in stages. The first design that really grabbed me was the Yoga. The convertible thing works for me and my needs, and the design is superior to, say, a tablet wrapped in a keyboard case.

Your big question, of course, comes back to MIPS, and this is really a religious issue. Do we want our MIPS in the cloud or on our lap? There are good arguments both ways. Obviously, Intel's substantial PC group prefers them in our lap. My daily struggles with Google Voice tell me that this is a worthwhile thing. Now, if carriers improve and whatnot, and I'm able to get the same class of perceptual computing performance from the cloud on my phone that I can get on my lap in an Ultrabook, I think the weight of judgment must finally fall in the cloud's favor. It's more efficient on all counts. (I'm ignoring security concerns for the sake of argument.) But when I'm using my phone to compose notes or story chapters or whatever, which I do every day, then all I care about is accuracy, speed, and my total productivity. If the Ultrabook effort fosters a notebook ecosystem in which I can get better results for my needs from a two-pound convertible, then I'm all about the convertible and totally behind Ultrabook. I'm selfish that way.

In short, we may find that the Ultrabooks of 2015 don't offer you enough extra value to justify your extra $200 or $300. However, I'd wager that at least some of the benefits you will enjoy in your non-Ultrabook, mainstream laptop of 2015 would not exist at their then-current level of development without Intel having made the investments in Ultrabook I've described in this article.

And what if Google and Apple and whomever manage to saw Intel's legs off and leave the notebook paradigm in the dust? Well, that's how it goes. The market decides what has value and what doesn't. That trend has already started. The question now is whether it will continue.

-

williamvw Reply

Oh, my gosh -- ANOTHER accusation of bribery! How novel! Well, since you managed to deduce that much on your own, geeze, lemme think... How much did they offer to pay me? Oh, I remember! It was http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DJtHL3NV1o!!! Because that's how globe-spanning $115 billion companies get to $120 billion, by putting their reputations on the line and bribing little journalists like me to write articles about historical developments just like this one.11277068 said:How much did Intel pay you to write this ? , we all know that ultra books sales are below freezing