China's chip champions ramp up production of AI accelerators at domestic fabs, but HBM and fab production capacity are towering bottlenecks

But what about performance?

Chinese companies Huawei and Cambrincon have begun to ramp up their production of AI accelerators at China-based fabs, according to J.P. Morgan (via @rwang07) and SemiAnalysis. If everything goes as planned, China will get over a million domestically developed and produced AI accelerators in 2026 from these two companies alone. This will hardly be enough to dethrone Nvidia's AI GPUs in the People's Republic, but it will certainly be a major step towards AI self-sufficiency.

However, it remains to be seen whether Chinese industry can produce millions of AI accelerators, as there seem to be two major bottlenecks — advanced semiconductor fab capacity and HBM memory supply. Furthermore, it remains to be seen whether these processors can deliver sufficient performance for China's AI industry.

No more TSMC for Chinese AI companies (well, almost)

Although it was widely believed that Huawei produced a significant portion of its Ascend 910B accelerators at Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp.'s (SMIC) fabs in China, the company actually used shell companies to place orders with TSMC and deceive the world's largest foundry to make Ascend 910B silicon.

In fact, virtually all of the China-based developers of AI accelerators — from Cambricon Illuvatar CoreX to Biren and Enflame — have either used, or continue to use, TSMC's services. However, only Huawei has managed to deceive TSMC and have a high-performance AI processor fabricated in Taiwan despite being on the U.S. Department of Commerce's Entity List that prohibits TSMC (and other companies) from working with the Chinese high-tech giant.

Since blacklisting Huawei in 2020, which obliges companies to obtain an export license from the U.S. government to ship any device containing American technology to the company, the U.S. government has put numerous China-based developers of AI accelerators and CPUs into its Entity List and introduced quite serious sanctions against China's AI/HPC and semiconductor sectors. As a consequence, only a handful of companies from the People's Republic can use TSMC services involving more or less sophisticated process technologies. Those who can still work with TSMC now produce simplified designs (up to 30 billion transistors on 16nm-class production node) packaged by a trusted OSAT provider, targeting entry-level systems.

Time for SMIC to step in

While SMIC apparently did not produce AI accelerators for Huawei until fairly recently, the company has been making the company's HiSilicon Kirin 9000S and similar system-on-chips (SoC) for smartphones. This has not only helped Huawei to return to the market of high-end smartphones without using restricted processors and models from Qualcomm, but also enabled SMIC to polish off its 7nm-class (also known as N+2) fabrication technology. Keeping in mind that Kirin 9000S has a die size of around 107 mm2, whereas the AI accelerator Ascend 910B has a die size of 665 mm2, it makes a lot of sense to pipe clean the node using the former.

Both SemiAnalysis and analyst Lennart Heim estimate that Huawei illicitly acquired approximately 3 million Ascend 910B dies from TSMC in 2024, which would be sufficient to assemble around 1.4 to 1.5 million Ascend 910C neural processing units (NPUs) that use two Ascend 910B dies. 1.5 million Ascend 910C NPUs are sufficient for Huawei to continue equipping its own AI data centers with in-house AI accelerators and potentially supply them to third parties.

SemiAnalysis believes that Huawei would have run out of silicon by now, but its partner SMIC began to ramp up production of Ascend 910B (or whatever it is called) in the third quarter of 2024, gradually increasing output to alleged hundreds of thousands of units in the first half of 2025. That ramp is set to continue, enabling Huawei to build as many as 1.2 million Ascend 910B dies in the fourth quarter of this year, according to SemiAnalysis.

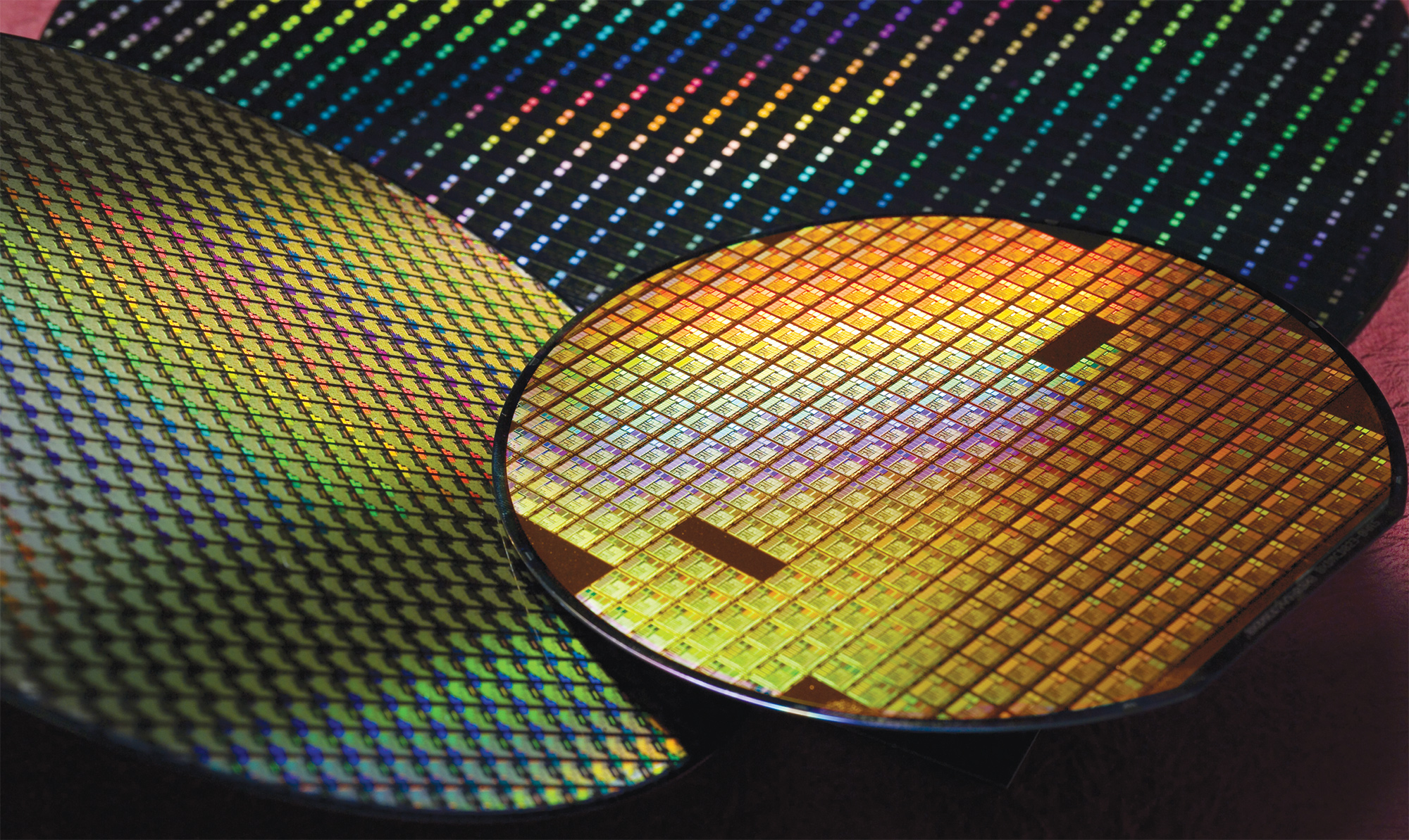

SMIC appears to have made progress with 7nm-class production technologies and can now produce significant volumes of Ascend dies. Analysts estimate that as few as 20,000 wafer starts per month (WSPM) could enable production of several million chips annually. SMIC's total advanced-node capacity is projected to reach 45,000 wafers per month by the end of 2025, expand to 60,000 by 2026, and 80,000 by 2027.

Of course, SMIC's 7nm-class yields remain below those of TSMC, especially for large chips like the Ascend NPUs. However, if SMIC allocates 50% of its output for Ascend, even at a below 50% yield, Huawei will get over 5 million Ascend 910B dies in Q4 2026, according to SemiAnalysis. The big question is whether even 2.25 million Ascend 910C processors will be enough to meet AI performance requirements in late 2026.

SMIC has bottlenecks

JP Morgan is a bit more conservative with its predictions about the production of Chinese AI accelerators, saying that Huawei will get 600 – 650 thousand of '700 mm2-equivalent' dies from local producers (which may include SMIC and perhaps Huawei's own fab, though it is unlikely that this fab is good enough to produce data center-grade chips at this point) this year and 800 – 850 thousand dies in 2026.

We do not know the die size of the Ascend 910B produced at SMIC, but it is likely that it is larger than that of the same processor made at TSMC, likely close to 700 mm2, so JP Morgan's estimates should be close to the number of actual NPUs that Huawei may get. The analysts also estimate that Cambricon can get 25 – 30 thousand large chips from SMIC this year, 300 – 350 thousand in 2026, and 450 – 480 thousand in 2027. Keep in mind that the current unit estimates reflect wafer-level production after wafer-in.

JP Morgan seems to be quite cautious about SMIC's output in general. Analysts from the company claim that it takes about six months from wafer start to chip completion, plus two more months for packaging and module assembly, so it essentially takes SMIC eight months to produce an Ascend 910C.

To put it into context, for TSMC’s 7nm-class process nodes (such as N7, N7+, N6), the typical wafer cycle time — from starting wafer to completed processed wafer — ranges between 90 to 100 days, depending on factors like process complexity and customer priority. For CoWoS-S advanced packaging, the lead time is somewhere between 30 and 60 days, depending on complexity.

SMIC's production cycle at 7nm-class nodes is roughly twice as long as TSMC's, primarily due to its reliance on DUV-only lithography with heavy multi-patterning. TSMC's N7 and N7P process technologies also relied on DUV lithography (only N7+ and N6 incorporate EUV, enabling them to simplify critical layers and reduce overall process steps), but their cycle was not that long. Perhaps, SMIC has fewer higher-end Twinscan NXT:1980i or NXT:2000i litho tools than TSMC, which creates a major bottleneck for large chips like the Ascend 910B, or maybe its fab is less efficient (e.g., has slower tools, less automation) in general. It is also unclear whether SMIC has advanced packaging in-house or has to turn to companies like JCET to fully assemble an Ascend 910C module.

If JP Morgan's assessment is accurate and SMIC/Huawei have major fab bottlenecks for 7nm-class fabrication technology and large chips, then ramping the fab up may be problematic without access to ASML's fairly advanced scanners like the Twinscan NXT:1980Di (unrestricted for China, restricted for SMIC) or NXT:2000i (a restricted tool for China).

As Huawei clearly knows that SMIC's capacity may not be enough to satisfy its demands for mobile application processors, CPUs, and AI accelerators, the company is simultaneously investing heavily in its own fabrication facilities. To equip them, it facilitated the creation of SiCarrier, a maker of fab tools with big ambitions, and bought $9 billion worth of fab tools in recent years to install them into fab(s), reverse engineer them, and build at SiCarrier.

If Huawei's fab project becomes a success, it will not only enable the company's greater control over its supply chain but will potentially free up SMIC capacity for other Chinese chipmakers such as Cambricon. However, rebuilding the whole wafer fab equipment supply chain may be too hard a task even for a company like Huawei because even to build a sophisticated DUV lithography system, it will need to replicate several industries, not just a tool from ASML or Nikon.

If there were no restrictions on advanced fab tools for China, companies like Huawei and SMIC would likely attempt to address the 7nm and possibly even 5nm and 3nm-class challenges with a brute force approach by simply procuring more tools. However, even if these companies manage to obtain plenty of ASML's NXT:1980Di for their fabs, they will still have to perfect techniques like self-aligned quadruple patterning (SAQP) and achieve decent yields, which could take years.

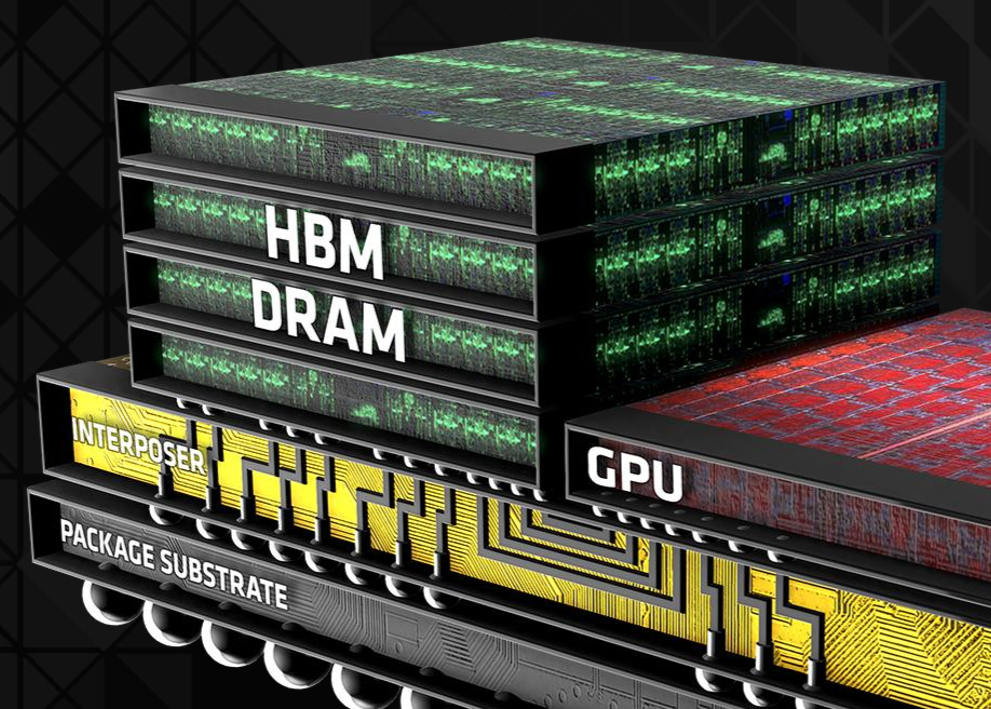

HBM bottleneck

But while the lack of advanced fab tools and production capacity for sophisticated nodes is something to be expected from the Chinese semiconductor industry, there is another, less obvious bottleneck for the People's Republic AI accelerators: HBM memory supply.

SemiAnalysis reports that Huawei's AI accelerator output could be limited not only by fab capacity, but by a shortage of HBM. The company had built up a large stockpile of HBM stacks — approximately 11.7 million units, with 7 million of those shipped in just one month by Samsung before U.S. export restrictions on HBM2E (and more advanced) were enforced in late 2024. While this stockpile has supported Huawei's Ascend 910C production so far, it is expected to be depleted by the end of 2025, which will stop production of these NPUs unless new sources are found.

China's main domestic DRAM supplier, CXMT, is racing to develop its own HBM capacity. The company has benefited from poached engineers, foreign equipment, and government funding, and can now manufacture DDR5 and early-stage HBM products. However, its projected output of ~2.2 million HBM stacks in 2026 will only support around 250,000 to 400,000 Ascend 910C packages, which is considerably less than what Huawei needs. While CXMT is rapidly expanding, including advanced packaging partnerships with JCET, Tongfu Microelectronics, and Xinxin, it still lacks the scale and efficiency of global leaders like Samsung and SK hynix.

As a result, Huawei and other Chinese companies may attempt to smuggle HBM produced by market leaders into the country to keep building their AI processors. However, given this constraint, China’s AI hardware industry may not be able to scale further unless it can overcome the HBM bottleneck.

What about self-sufficiency?

Being unrestricted in terms of access to advanced process technologies and HBM supply, Nvidia can produce millions of high-performance AI processors for China. As long as its products meet U.S. export controls requirements, the company can funnel millions of GPUs — whether these are relatively low-performance H20 or high-performance B30A — to China to meet demands of its partners like Alibaba or ByteDance.

Since both H20 and B30A seem to be cut-down versions of high-end H100 and B300, Nvidia's supply of such processors could also be limited, as the company would rather sell more full-fat GPUs. On the one hand, this means that China-based customers or Nvidia could acquire additional capacity from cloud service providers. On the other hand, this means that there is unsatisfied demand for AI processors in the People's Republic, a market that may well be addressed by domestic AI hardware companies.

However, recent rumors suggest that China's government wants Chinese companies to buy domestic AI hardware to strengthen the domestic industry. If China truly sets the goal for AI hardware self-sufficiency, then it may well use the brute force approach to production of AI hardware — both compute and memory — and make them regardless of yields and cost. However, given uncertainties with advanced fab capacity and HBM supply, this strategy may not work.

Furthermore, there are other obstacles like fragmented ecosystems and ubiquity of Nvidia's CUDA software stack that may prevent China from becoming self-sufficient in terms of AI hardware and software in the foreseeable future.

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.