SurgeX SA-1810 Tear-Down

Pushing Buttons

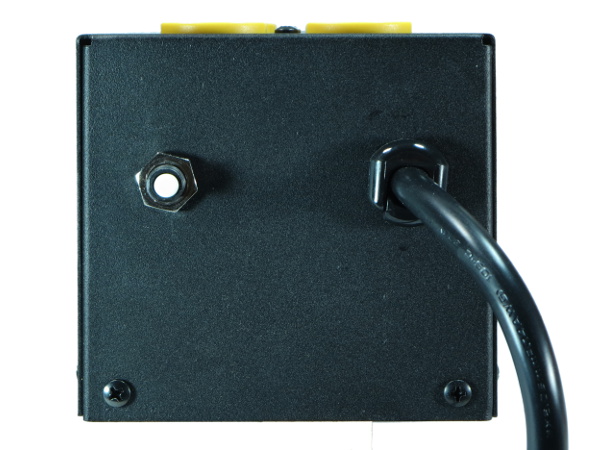

On the power cord entry side, we also have a plunger-style 15A circuit breaker. This concludes the preliminary exterior tour. If you are wondering where the switch is, there isn't any on this model.

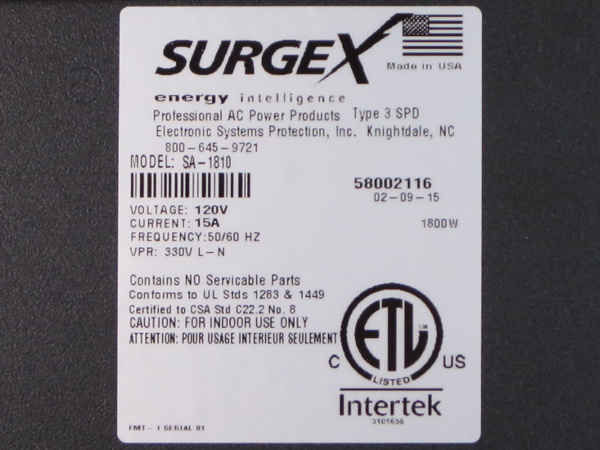

The Traditional Label Shot

No “Made in China” here. As you would or should hope to see on more premium products, ESP/SurgeX spared no expense on assembly by manufacturing these in the USA. Some of you might be wondering why a $400 product features the same 330V Voltage Protection Rating as $30 units. The reason for it is simply that 330V is the lowest or best protection rating defined in ANSI/UL 1449-rev3. As for what C22.2 no.8 is, it is just a Canadian complement to UL 1283 for EMI filtering.

Note the warnings. We get the usual indoor use only, accompanied by the timeless classic “no user-serviceable parts inside”, which I do not remember seeing much lately and will gleefully ignore as usual in a moment.

The A-1-1 Game

Here is that optional 1449 adjunct Commercial Item Description mentioned earlier. It is the main reason why people and companies fork over $300 for these and equivalents. While basic 1449 certification means a surge protector should not be a safety hazard and can suppress surges, it makes no guarantees about product endurance. Adjunct testing and certification addresses that.

Here, 'A' means the product suppressed 1000 worst-case surges (6kV at up to 3kA) without performance degradation, the first '1' corresponds to the 330V protection rating class, and the second '1' means no ground contamination – no surge current dumped to ground.

Put together, A-1-1 represents the best power line surge protection certifiable under ANSI/UL 1449-rev3. If your surge protection has no CID, it is not rated for endurance.

Unfolding At Home

Four self-tapping and six metal screws later, the bottom cover falls off from the top and the reason why the SA-1810 is the same or similar size to its two-outlet SA-15 variant becomes obvious: the box is actually full, which I suspected from its weight.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

In the back, we see the rear of those outlets. To the right, we find the breaker, and at the bottom-right, the load-side EMI filter board. Hiding under a sheet of insulation, the larger board hosts the surge clamping circuitry. Below it, you find SurgeX's reactor, the linchpin behind its Advanced Series Mode surge elimination.

Unplug Fest

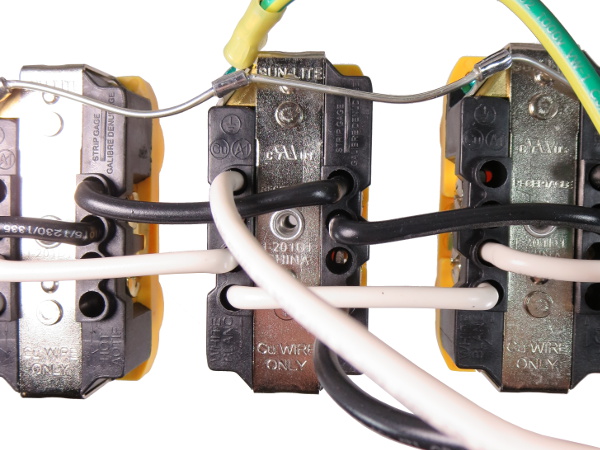

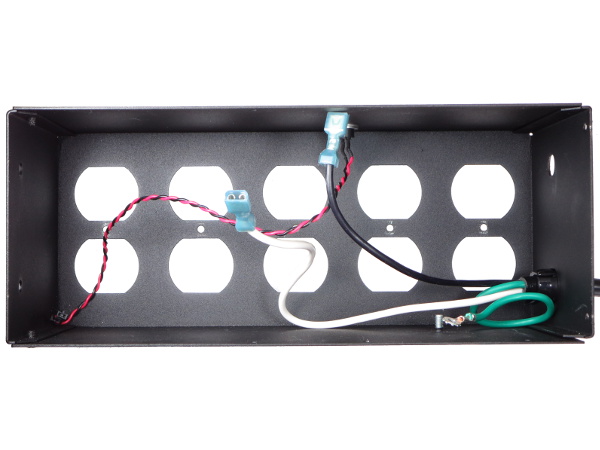

After disconnecting a handful of wires, the top cover can be separated from the base for a less cluttered view. These outlets look every bit as bog-standard from behind as they did from the front, making them very serviceable if need be. The top part's three ground wires (one from the power cord, one from the outlets and the other jumper from the bottom cover) join together on the stud near the bottom-right corner.

Letting It Out

You may remember me commenting how some manufacturers choose odd ways to route power to their strips' outlets. None of that nonsense here: power, neutral and ground are all attached to the middle outlet, then fanned out both ways from there.

These outlets look like decent quality and are the rear-entry type with screw-driven wire clamps for live and neutral, which makes them very reusable and replaceable. When I replace outlets for friends and family, this is my preferred wire attachment style to work with.

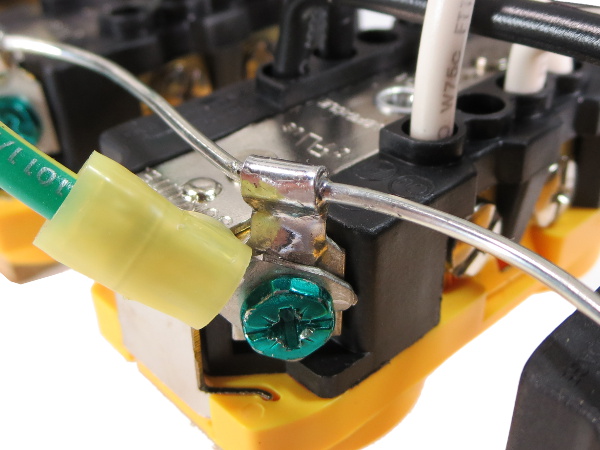

Bonus Point For Effort

Instead of looping the solid ground wire around the ground screws and tightening them, ESP/SurgeX went through the extra trouble of folding fork connectors with metal tabs over the tin-plated wire and soldering them. There was somewhat of a solder spill here, but the electrons won't mind.

Breaking Up

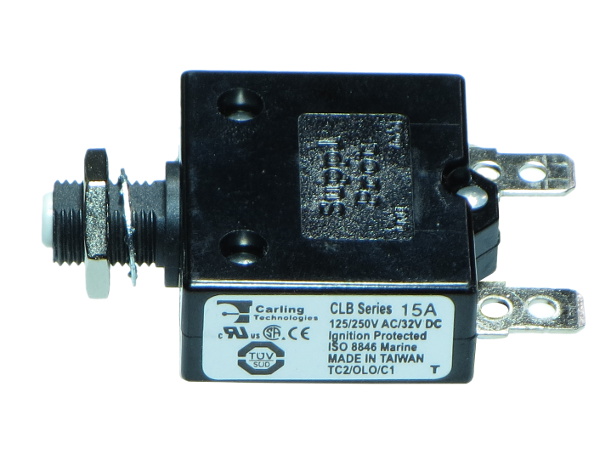

Unsurprisingly, we find a breaker rated for 15A. Less common is the mentioned ISO 8846 compliance, which pertains to safety in explosive marine craft environments, meaning the breaker is sufficiently gas-tight and thermally isolated to prevent arc heat from detonating an explosive propane-air mix.

One Gauge To Rule Them All

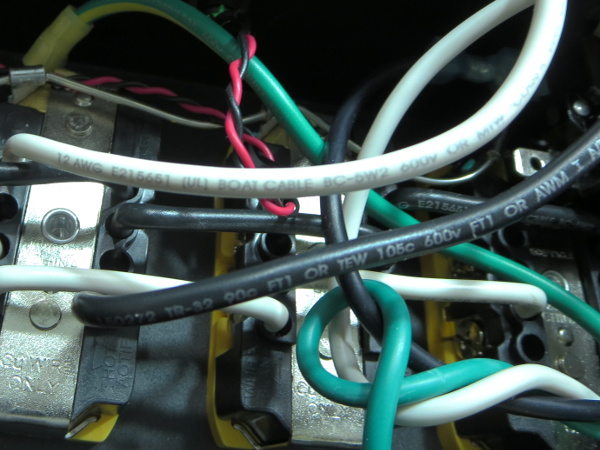

While the power cord is the expected 14-gauge copper and 300V insulation rating for a 120V/15A product, all other visible leads and jumpers within the unit are 12-gauge, 600V “boat” cable. With the margins SurgeX earns on these, I would not be surprised if it decided that shaving quarters on manufacturing separate parts for the company's 15A and 20A products was not worth the trouble and potential risk of putting 15A wires in 20A models. As for the higher insulation voltage rating jumpers, the thicker and more tightly controlled insulation reduces the risk of having an insulation breakdown event within the unit during endurance testing or after years of field exposure.

Empty House

With the outlets and breaker gone, the top looks so much roomier. Even with all of the screws removed, the folded sheet metal enclosure remains reasonably stiff, as you would expect from what appears to be 1.3mm (0.05”)-thick steel.

-

Evil_Overlord Thank you for this write-up. In my eyes, this article is a shining example of what (technical) journalism should be. It is both worthy of being used as a product review, and reference guide. If I were going shopping for a series-mode surge suppressor, or if I knew someone who was shopping for a power protection solution for power-sensitive equipment, I would -without pause- recommend using this article as a launching pad for any/all research.Reply

Two things in this article stand out and gave me a reason to write this comment. First: You didn't give up. When faced with equipment that could not perform all the tests you desired, you switched to a simulated circuit. That takes time, research, and effort. Second: You openly admitted the transition from real-world to simulation. Lesser authors might skipped that disclaimer.

Well done. -

mortsmi7 They go to all the trouble of making such a beefy product and then they back-stab the outlets. The cross-section of a stab connection is very low compared to a screw-type. A space heater, which applies a constant high amperage, will kill a back-stabbed outlet in no time.Reply -

Daniel Sauvageau Reply

They make models for just about every country, you just need to go through surgexinternational.com to pick your country. All they need to do is put the appropriate cord and transformer/reactor in, increase the bleeder resistors' value for 220-240V countries and that's probably it*.16422851 said:Interesting , do they have a European version of this ?

Edit: *and put 400-450V electrolytic input caps in instead of 250V since 240V crests near 350V.

Thanks.16423853 said:Thank you for this write-up.

Two things in this article stand out and gave me a reason to write this comment. First: You didn't give up. When faced with equipment that could not perform all the tests you desired, you switched to a simulated circuit. That takes time, research, and effort. Second: You openly admitted the transition from real-world to simulation. Lesser authors might skipped that disclaimer.

Well done.

I had already done a fair chunk of the simulation research almost a year ago after getting into an argument with some readers about SurgeX and similar products, so I was basically biting my time to do something with the results and what I learned during that process.

As for admitting to using simulated results, this simply requires a lot less effort than producing convincing fake results. The main reason I do it though is as a shout-out to test equipment manufacturers: "if you had sponsored me with test equipment relevant to this story, your gear would have probably been shown or at least mentioned here." -

Daniel Sauvageau Reply

These are not "stab" connection with the crappy leaf-springs snaring wires. They are captive nut connections: the wire gets secured between the captive nut (a piece of cast metal with a tapped hole the terminal screw screws into and grooves to guide the solid copper wires) and screw/terminal by tightening the screw.16424079 said:The cross-section of a stab connection is very low compared to a screw-type. A space heater, which applies a constant high amperage, will kill a back-stabbed outlet in no time.

As far as current-passing capacity, those captive slab types should be every bit as good as plain screw terminals: they are basically the same except that instead of the wire being squeezed directly between the screw and outlet metal strip where you need to wrap the wire around the screw just so it does not slip out from under the screw while tightening, the wire is squeezed between the captive slug and the metal strip with the groove guiding the wire in place, eliminating the need to wrap the wire around the screw. These same grooves might actually provide more total contact area with the wire than the screw head does. -

blackmagnum Thanks Daniel for the tips. When using $1k plus computer equipment at work or home, it has been proven that you should play safe with reputable power delivery than be cheap and sorry.Reply