How is 3D Printing Filament Made?

We toured three factories in person – and one virtually – to find out.

Every good 3D print starts with plastic, usually in the form of colorful strands wound neatly on spools. Though the 3D printing hobby is jampacked with do-it-yourselfers, making your own filament is still out of reach for most home workshops. High-quality filament requires expensive heavy-duty machinery, a lot of space, and a ton of energy.

I’ve had the opportunity to visit three factories making 3D printing filament in person, and a fourth virtually: Prusa Research, Printed Solid, Printerior and ProtoPasta. They all use the same basic principle: mix plastic pellets with color and property enhancing additives; melt it, extrude it, cool it, and wind it on a spool. Easy, right?

David Randolph, CEO of Printed Solid in Newark, Delaware, recently gave me a tour of his factory’s four filament lines. Three were built by his company to produce affordable PLA and PETG, under the brand name “Jessie”. The fourth was installed by Prusa Research after his company’s friendly acquisition by the Czech Republic manufacturer. I was asked to not take any photos of the Prusament line, to avoid leaking company secrets.

Jessie PLA is on our list of Best Filaments for 3D Printing as our favorite budget PLA and still only costs $19.99 a spool.

It Starts with Plastic Pellets

All spools of filament start with raw plastic pellets, the most common being PLA (Polylactic Acid), a biopolymer made from plant materials such as corn, sugarcane or beets. Other materials, like PETG, ABS, ASA, PC and Nylon are made from petroleum based sources.

The first step to turn pellets into filament is drying, as the plastic readily absorbs moisture in its raw form. Large scale manufactures use vacuum hoses to move pellets from the shipping containers into the drier and then to a hopper at the start of the manufacturing line.

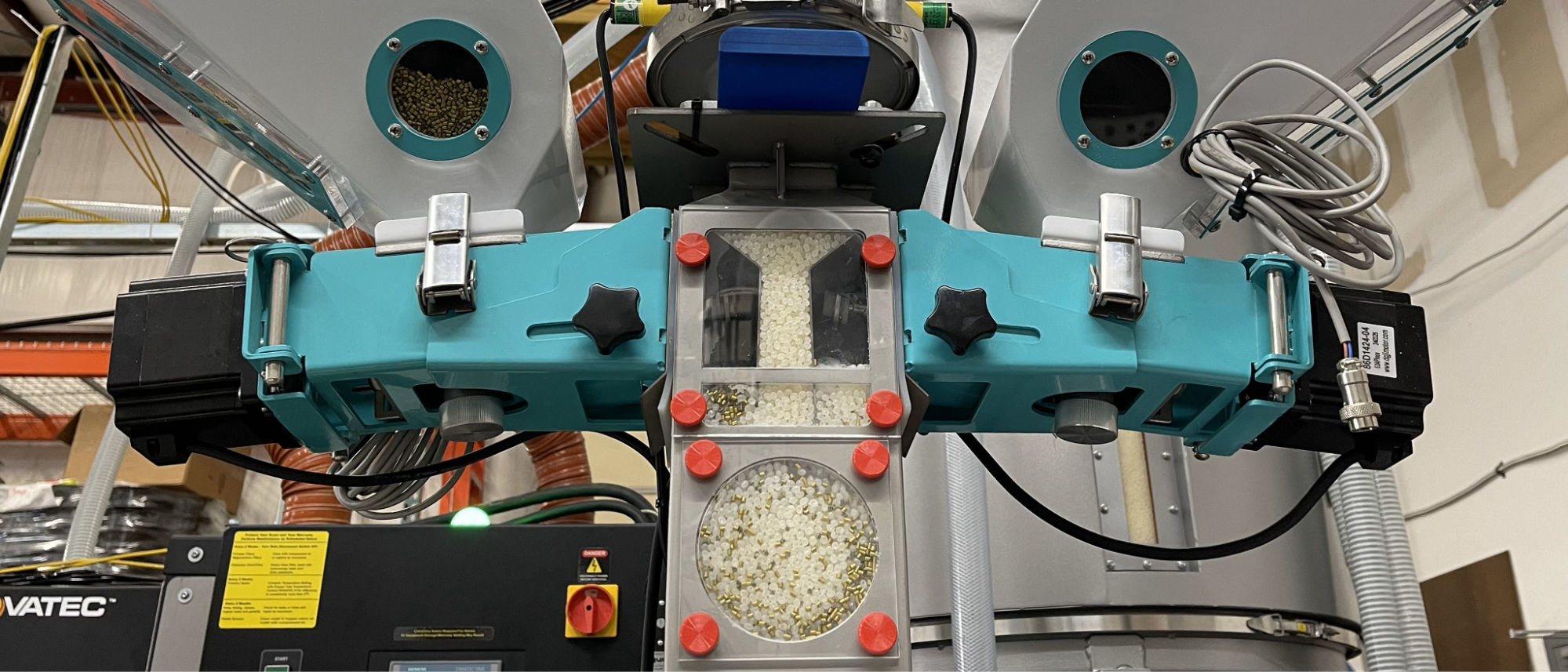

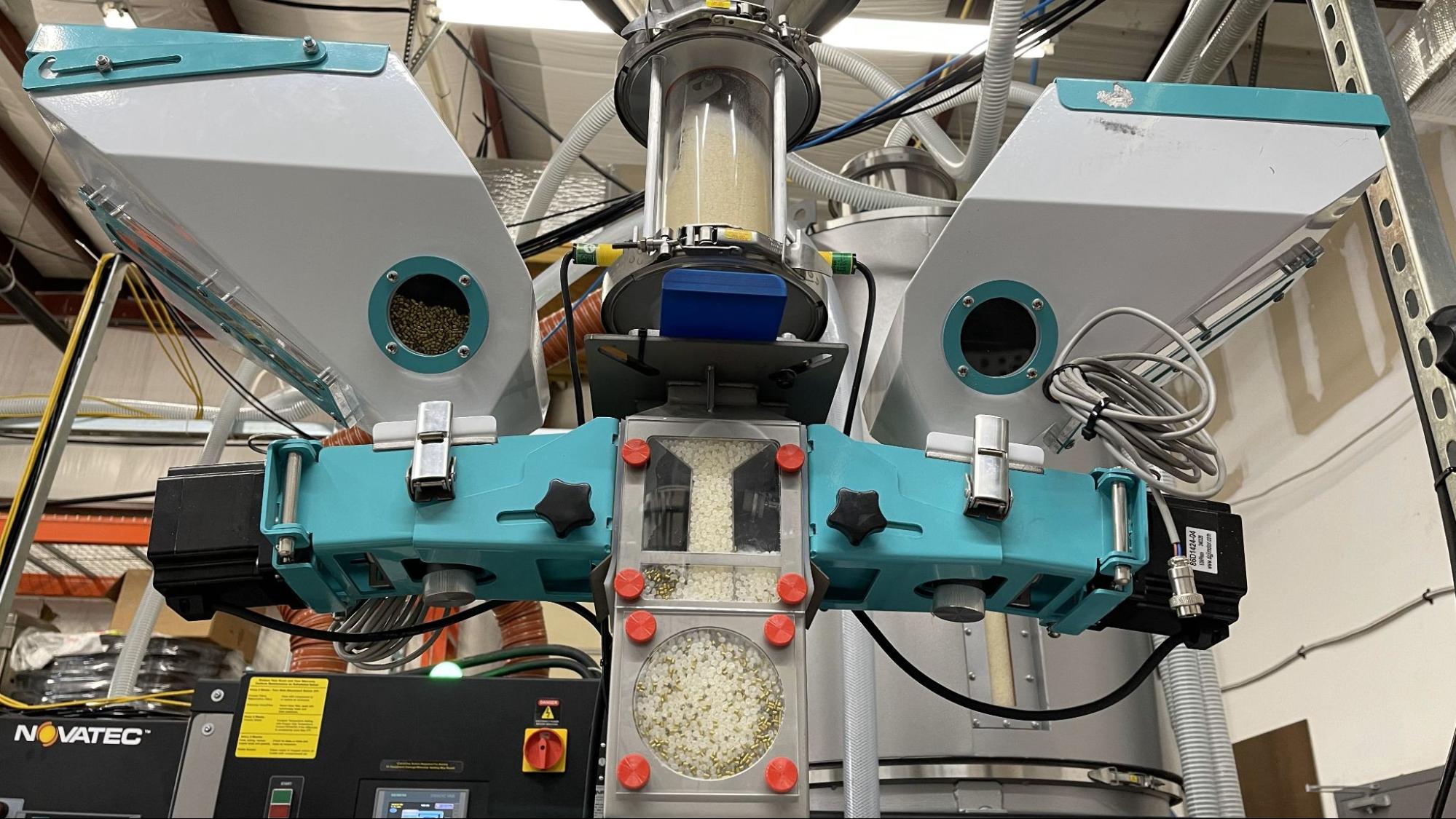

Recycled filament starts off in a similar fashion, but uses pellets made from melted down shredded filament and a bit of unused raw material as needed. In the photo below, you can see the start of Prusa Research’s recycled filament line, with one hopper labeled “regrind” and the other “natural”. Prusa melts factory scraps into 2kg spools of recycled filament, which is sold at a cheaper price.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Adding Color

Randolph said Printed Solid’s Jessie filament is made using raw PLA or PETG mixed with a sprinkling of masterbatch, which is a highly concentrated colorant made to order by a plastics company in Chicago. They purchase a year’s supply of color at a time to maintain consistency. The ingredients of any one masterbatch is a highly guarded secret, but the pellets can contain both pigment and any additives such as glitter, mica or even TPU for a silky finish.

Some manufacturers, like ProtoPasta, create their own masterbatch in house, using powdered pigments and additives that are carefully mixed in smaller batches. This technique allows them to quickly release new colors or offer in house workshops where customers can make their own small batches of custom color.

The photo below shows how raw pellets are mixed by machine with masterbatch pigment to make Jessie Golden Winner PLA. Randolph said the advantage of using masterbatch pellets are the ease of cleanup when the line switches color. With only three machines to make over 35 colors in both PLA and PETG, there’s a lot of cleaning going on. Prusament is handled in a similar manner.

The pellet mix is fed into a heated extruder with a long screw that blends the materials together as they are melted. Randolph said this is the same kind of extruder that would feed an injection molding machine used by other plastics manufacturers. The screw is inside a long metal tube with six heated sections to gradually heat the material to the required temperature while being pushed to the nozzle.

The filament is 3mm wide after leaving the nozzle. It immediately goes into one of three long, skinny tanks of water – one hot, one warm and the last one cold, to cool the filament and set its shape. Randolph explained that the water bath also supports the filament so it maintains a smooth, even shape. By the time the filament reaches the end of 40 foot bath, it has been gently stretched to its final 1.75 mm diameter.

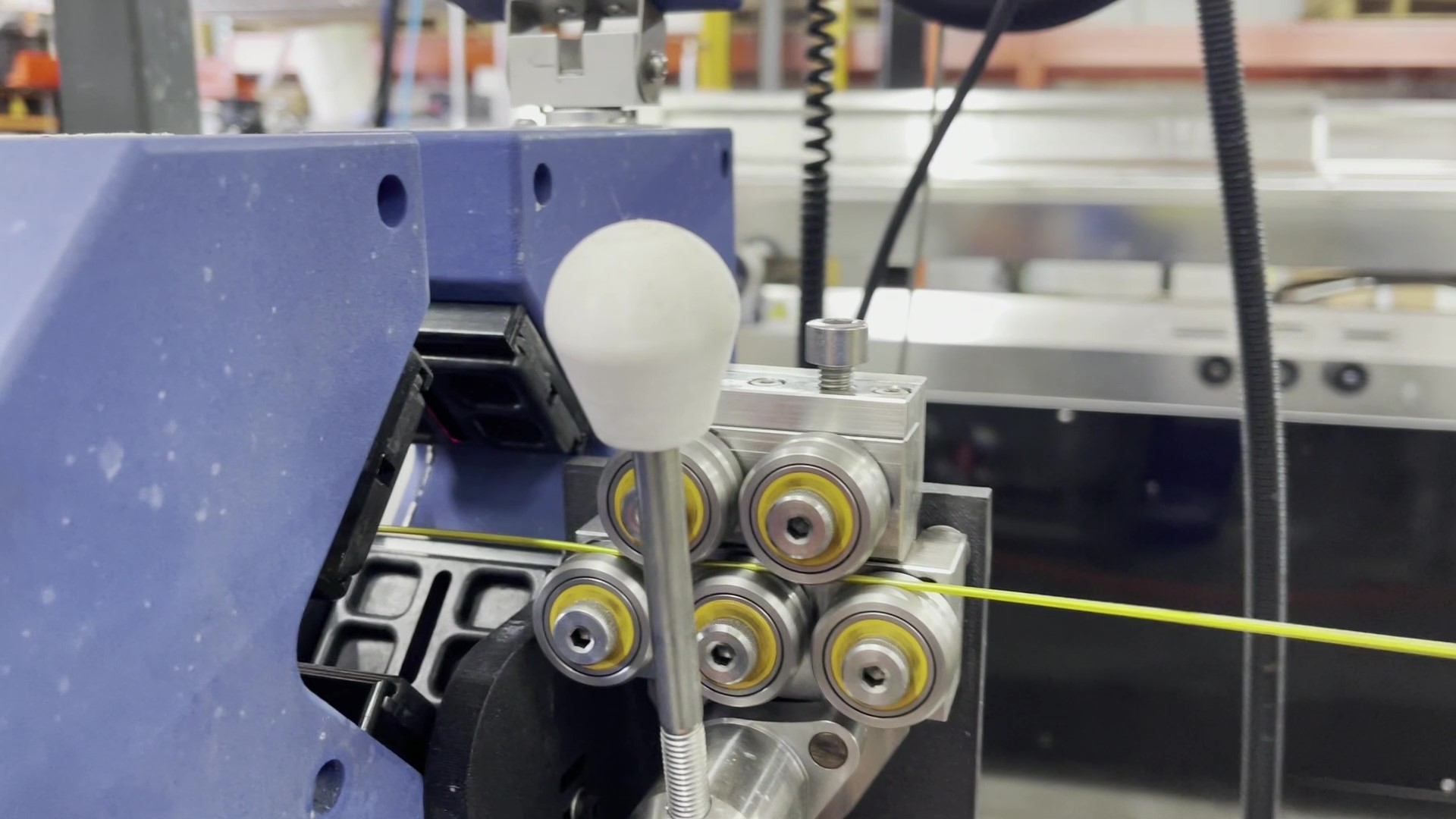

After the water bath, the filament travels through a pair of lasers to check the size and shape of the strand. The Jessie line produces an oval shape that is 1.75mm diameter with a tolerance of -0.02mm across two axis, the same as the Prusament line. These measurements are critical, as drifting even to 1.8mm in diameter can jam your 3D printer hotend.

Next, the filament travels through a buffer, which takes up slack while spools are loaded and unloaded at the end of the line by the operator. The line never stops moving during production.

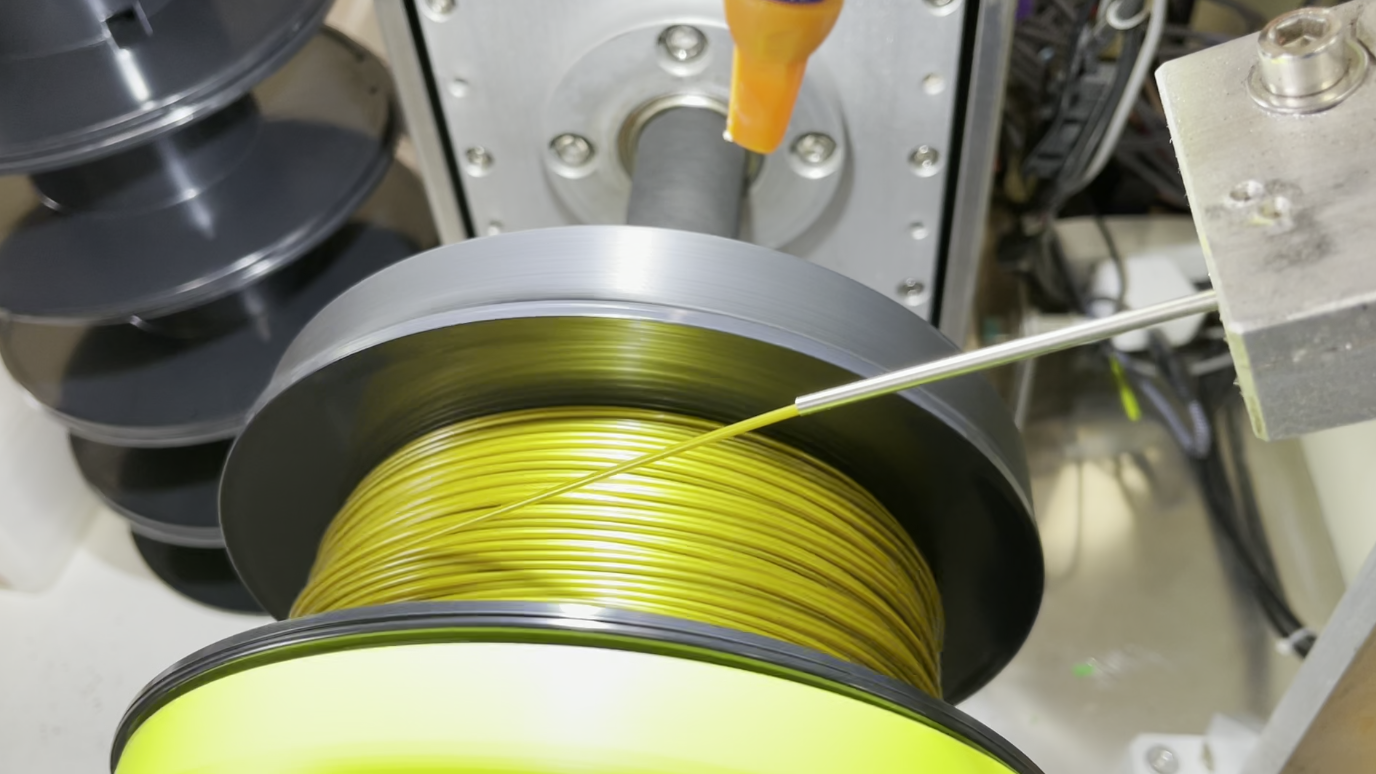

Finally, the filament is collected on a 1KG spool, then packaged for the customer. It takes less than 5 minutes to make one spool, which is pretty amazing.

Randolph said his goal is to create the best affordably priced, made in the USA filament possible. The spool is one way he’s been able to keep prices down – rather than ordering custom spools, he buys less expensive welding wire spools made by a company in Ohio. Another cost saving measure is minimal packaging. Since Jessie filament is only sold directly from the factory, it’s stored in vacuum sealed bags then shipped in a plain cardboard box.

Prusament has one extra finishing step. Where the Jessie filament gets a simple sticker, Prusament spools are put on a laser to etch the name of the filament and also provide tracking via a QR code. This code provided the user with data from the filament line while that spool was being made. Once labeled, the spool is sealed and boxed.

MORE: Best 3D Printers

MORE: Best Budget 3D Printers

Denise Bertacchi is a Contributing Writer for Tom’s Hardware US, covering 3D printing. Denise has been crafting with PCs since she discovered Print Shop had clip art on her Apple IIe. She loves reviewing 3D printers because she can mix all her passions: printing, photography, and writing.