Intel Invests $4.6M Into Eye-Tracking Company AdHawk, Competition Heats Up

Intel has invested $4.6 million in AdHawk Microsystems, a company that makes camera-less eye tracking. This news is the latest in the arms race around the technology, which remains one of the next needs for both VR and, more importantly, AR.

Competition

Big companies are starting to swallow up eye tracking outfits. Facebook/Oculus bought Eye Tribe at the end of 2016, Google bought a company called Eyefluence, and Apple snapped up SMI this summer. The SMI acquisition was a particular coup, because prior to being bought by Apple, we found SMI’s promising tech in both an HTC Vive demo and as part of Qualcomm’s VR accelerator program.

Other eye-tracking companies remain independent, such as Fove, QiVARI, and Tobii.

The Tech

But according to AdHawk, what sets its technology largely apart from the competition is that it doesn’t use cameras.

Camera-based eye tracking essentially works by taking hundreds of pictures per second of the eye and using algorithms to sort them out and and determine position. They also can require especially bright LEDs to light your eyes for the cameras. That all introduces latency and requires power, however small.

By contrast, AdHawk describes its microsystem thusly:

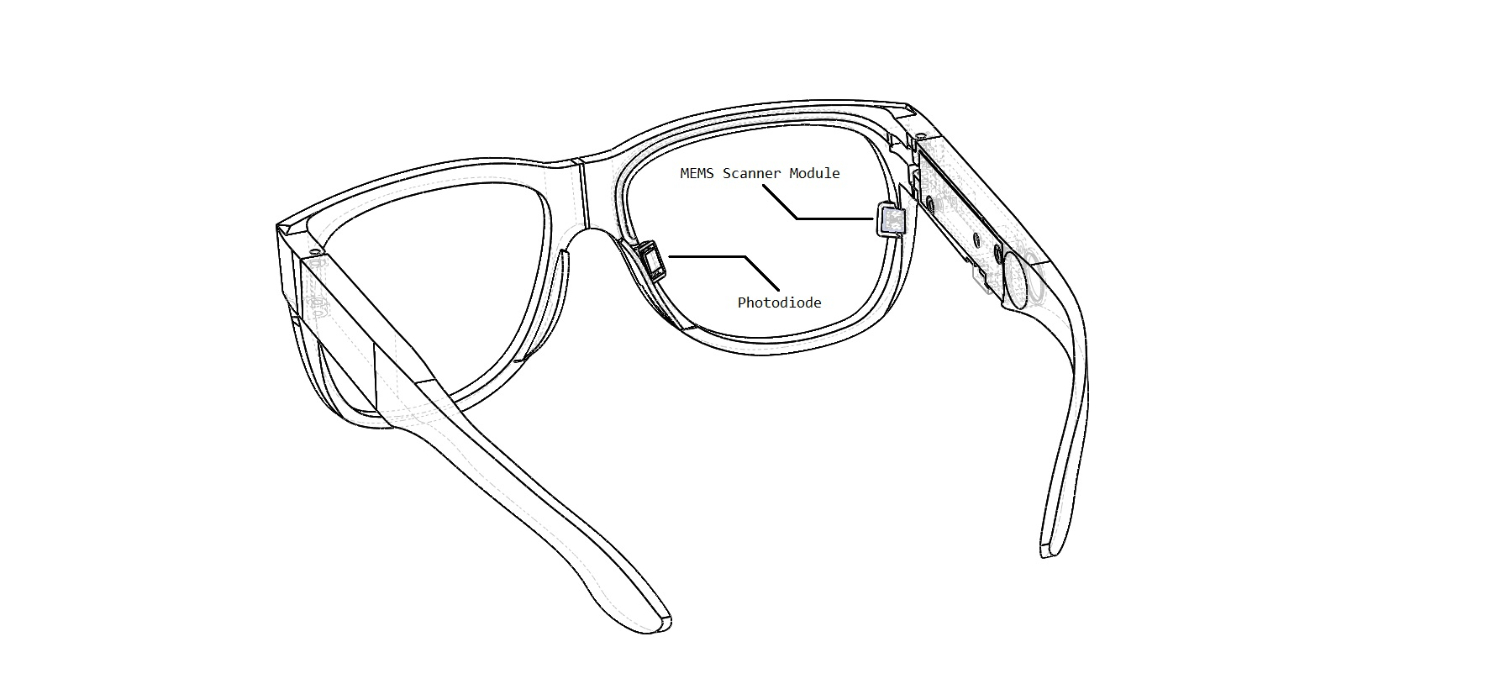

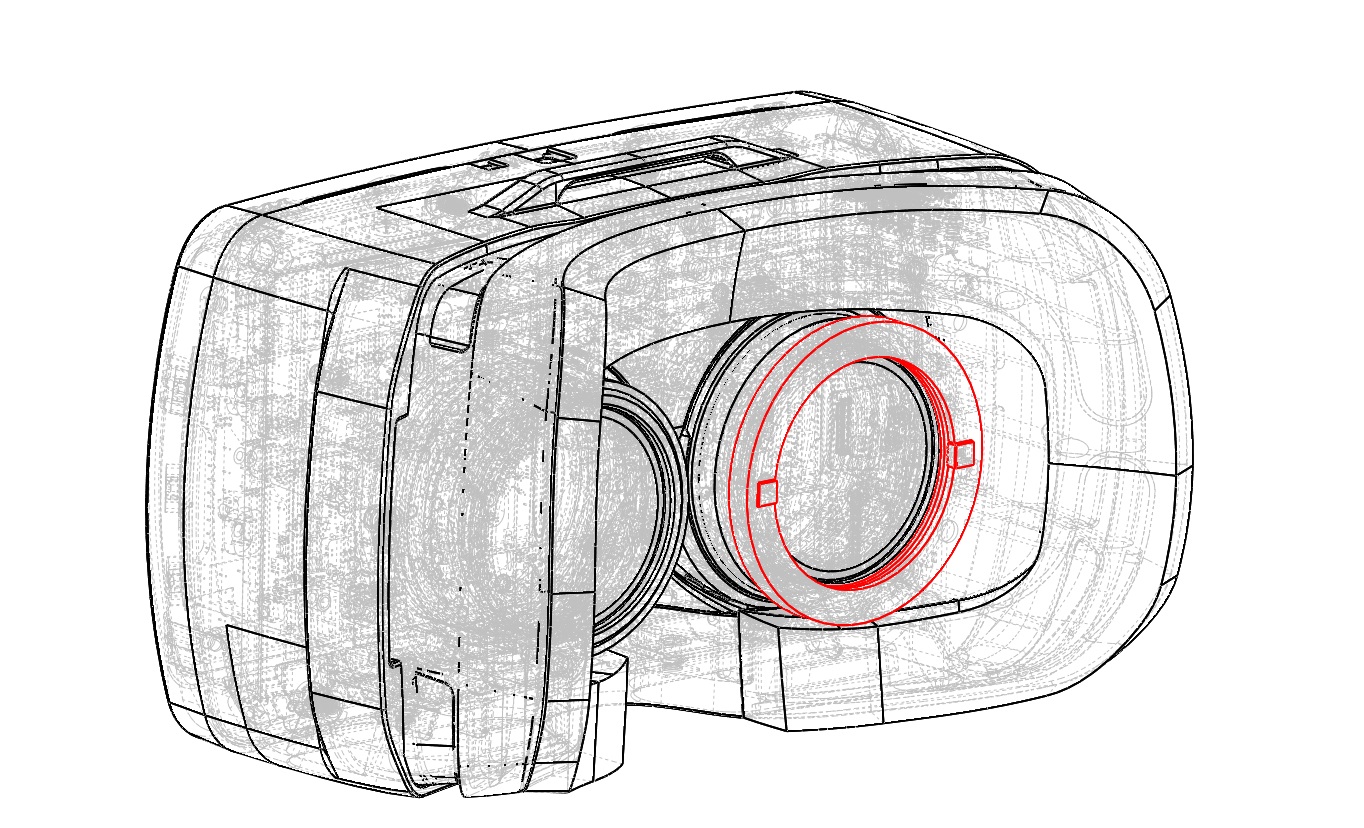

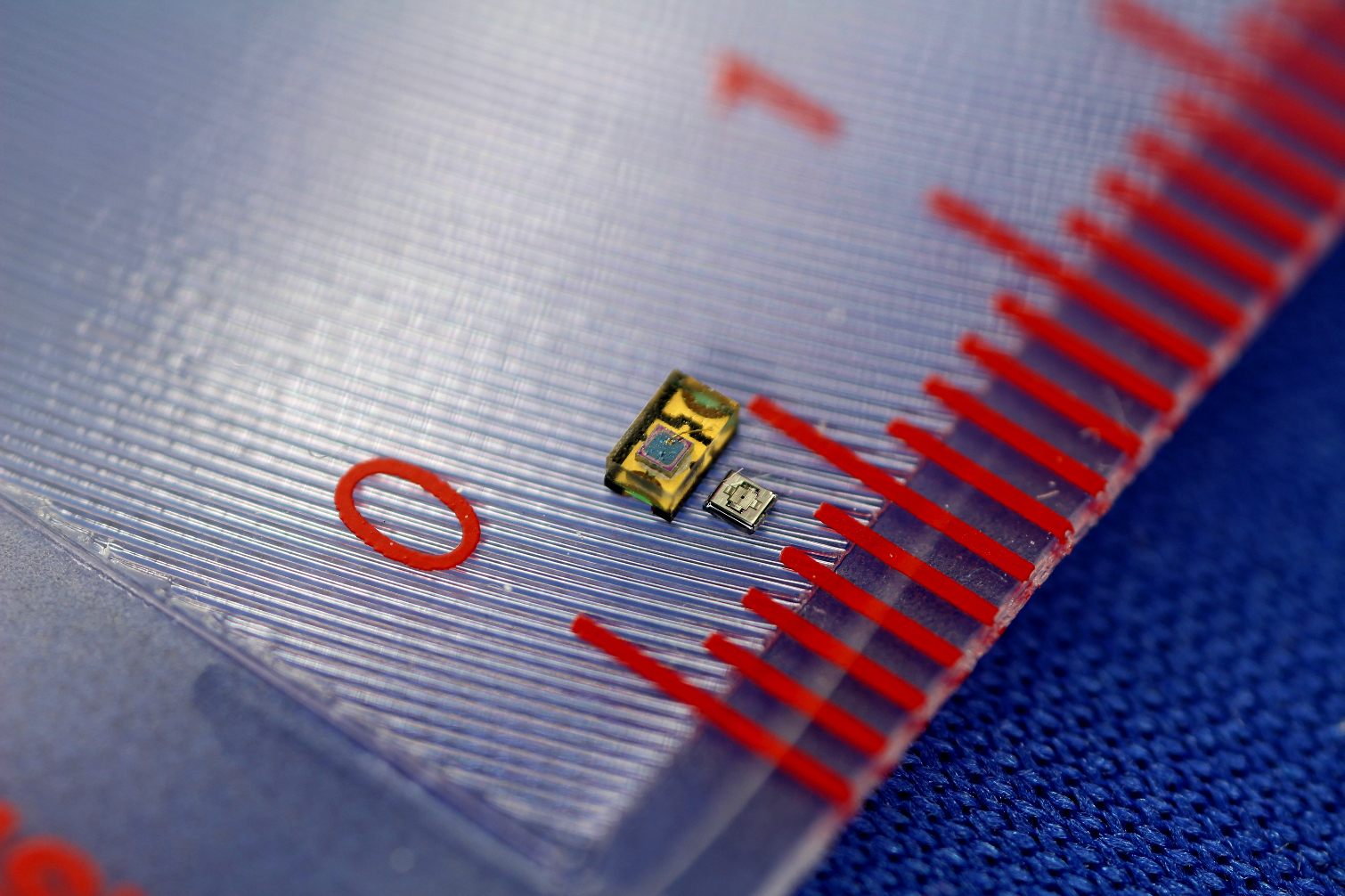

AdHawk’s eye tracker replaces the cameras with ultra-compact micro-electromechanical systems – known as MEMS – that are so small they can’t be seen by the naked eye. These MEMS eliminate power-hungry image processing altogether, resulting in order-of-magnitude improvements in the speed, form factor and energy efficiency of the VR/AR units that carry them, while delivering resolution on par with expensive, research-grade systems.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

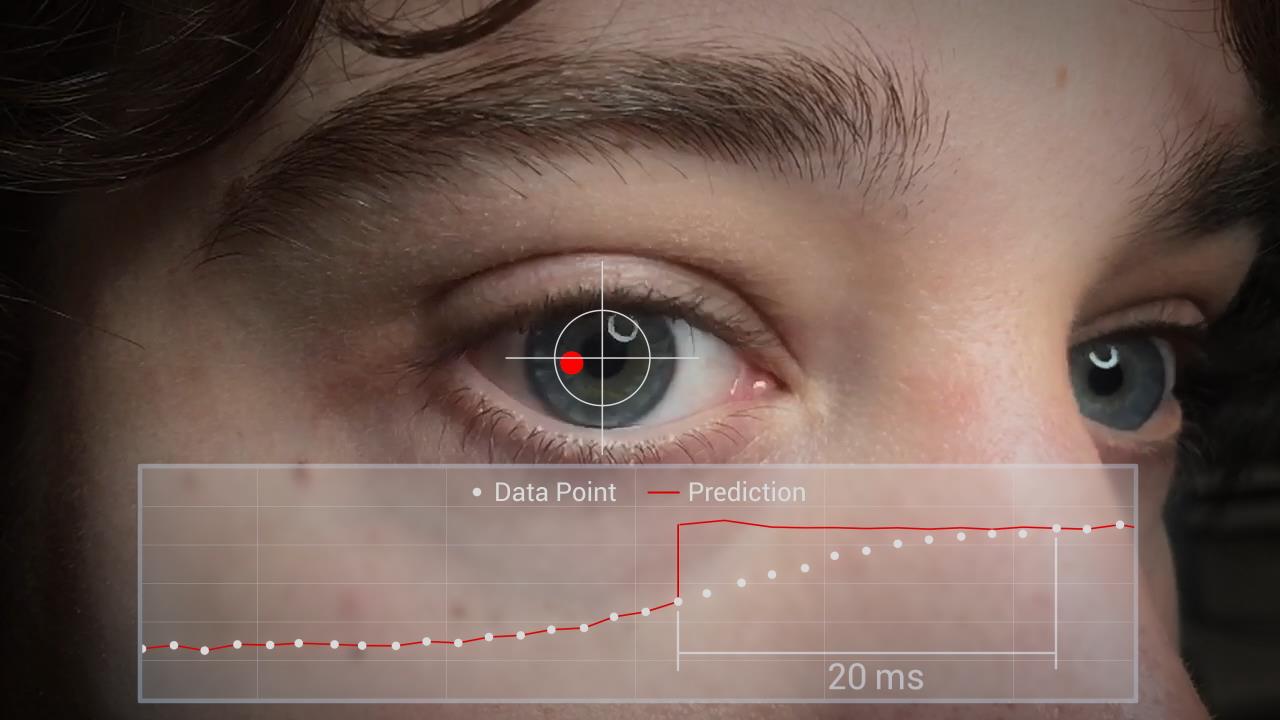

Like some other eye tracking solutions, AdHawk’s technology predicts where you’ll look next up to, it claimed, 50 milliseconds in advance. The MEMS system has an LED beam that scans the eye, and using a photo diode, can detect eye position. This all runs on a CMOS, although it’s not using the CMOS to build an image.

AdHawk said that its solution requires precious little power, claiming that it could run for a full day on nothing more than a coin-cell battery. Further, the design consists of just two chips and a serial protocol (a three-wire interface). Ostensibly, the whole eye tracking system is incredibly lightweight in every sense of the word, making it ideal for virtually any headset, tethered or mobile.

AdHawk wouldn’t be pinned down on cost, but representatives did tell Tom’s Hardware that it’s a volume play. They’re manufacturing at wafer scale to reduce costs, anticipating a high volume of system integration. That should put the price at around $10+ per eye, although of course the actual cost will vary quite a bit depending upon volume and the difficulty of a given system integration. (For example, if AdHawk has to provide more support services during that process, the costs go up.)

Why It Matters

There are numerous use cases for eye tracking. Outfits like Tobii have employed it for research purposes, such as sending someone wearing Tobii-equipped smart glasses through a store and tracking what they look at to gauge the effectiveness of displays or using it to perform health evaluations. Tobii also has a gaming wing, and that part of the company has developed both standalone trackers that mount on your monitor and help you navigate a game, as well as integrated tracking on gaming laptops (for the same purpose).

But eye tracking can make VR experiences better, too. For example, if the system knows where your eyes are looking, it can better help you make eye contact with other humans (represented by avatars) in a shared experience or with virtual in-game characters. It can also help with navigation, potentially solving some locomotion issues, and/or just enhancing the games or experiences you’re playing. It’s also key to foveated rendering, which is a technique that can potentially reduce the GPU requirements of a given title and can therefore enable better VR experiences on less-powerful hardware.

In AR, it has even more potential uses. The holy grail of AR is a set of smart glasses that look like regular spectacles but have as much power as a smartphone, providing the wearer with a HUD that can show you everything from email and social media notifications, to map overlays that help you get around a new city, to pop-up information on products and location, to AR games like Pokemon Go. Eye tracking is part and parcel of all of the above; when the smart glasses know what you’re looking at, it can serve up the best information in the most comfortable way, and can also let you interact with the real and the virtual more effectively.

AdHawk has its sights set on essentially all of the above. Notably, the company claimed that its technology can be used to detect things like your emotional state or if you’re especially tired or confused. This is not to mention early detection for ailments such as Parkinson’s Disease or Alzheimer’s. You can have tests for disease detection performed in a lab, but as AdHawk representatives pointed out, you would have to go to a facility and get screened on purpose. If you’re already regularly wearing a device that’s looking at your eyes, though, the system could track any changes and alert you.

Also, despite the intriguing buy-in from Intel, don’t expect vertical integration; AdHawk’s intent is to go wide and get its tech into any and all HMDs it can.

What’s Next: 3D Gestures

The funding from Intel, we were told, should get AdHawk through the next 18 months and help it acquire manufacturing capabilities, but it will also fund the company’s next project: a 3D gesture sensor.

This sensor projects a sphere (10cm volume), around, for example, a watchface. It purportedly can detect gestures within a 25-micron resolution on the X, Y, and Z axes. For example, you could swipe a smartwatch keyboard in the air instead of having to actually touch (and therefore, immediately visually occlude) the watchface itself. It could also be used to offer a virtual keyboard on any surface.

AdHawk described this technology as “a low-power, ultra-precise gesture sensor and a point cloud scanner module for super-resolution 3D sensing.” With it, the company is again leveraging MEMS technology. It borrows much of its technology from the eye tracker, in fact.

For now, though, AdHawk is pushing its eye tracking technology. HMD makers can request a device and an evaluation kit by contacting the company directly.

Seth Colaner previously served as News Director at Tom's Hardware. He covered technology news, focusing on keyboards, virtual reality, and wearables.