Aerocool Project 7 850W PSU Review

Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

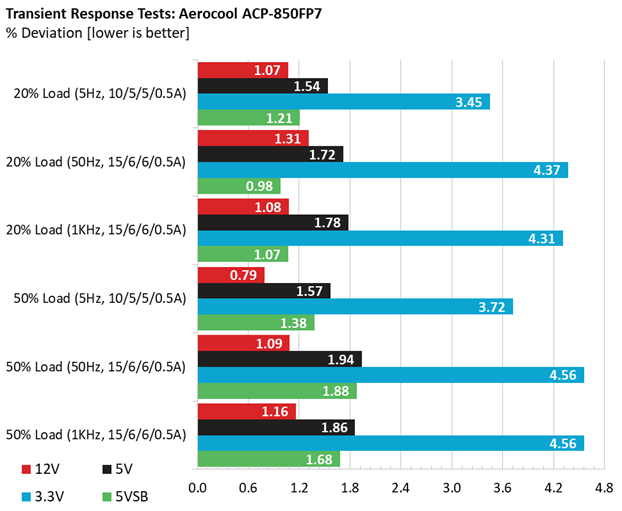

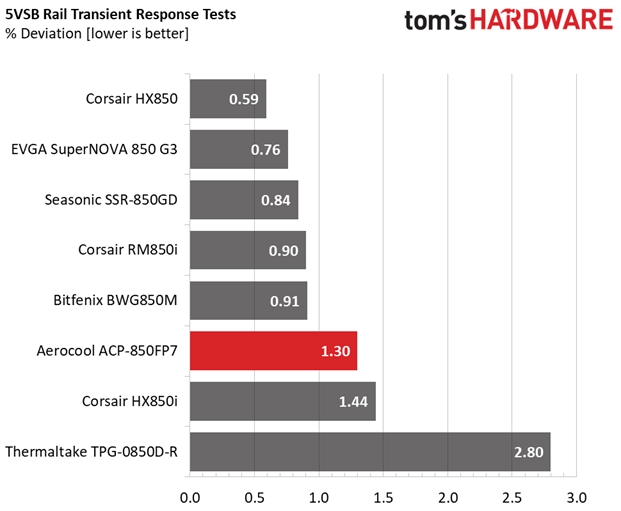

Transient Response Tests

Advanced Transient Response Tests

For details on our transient response testing, please click here.

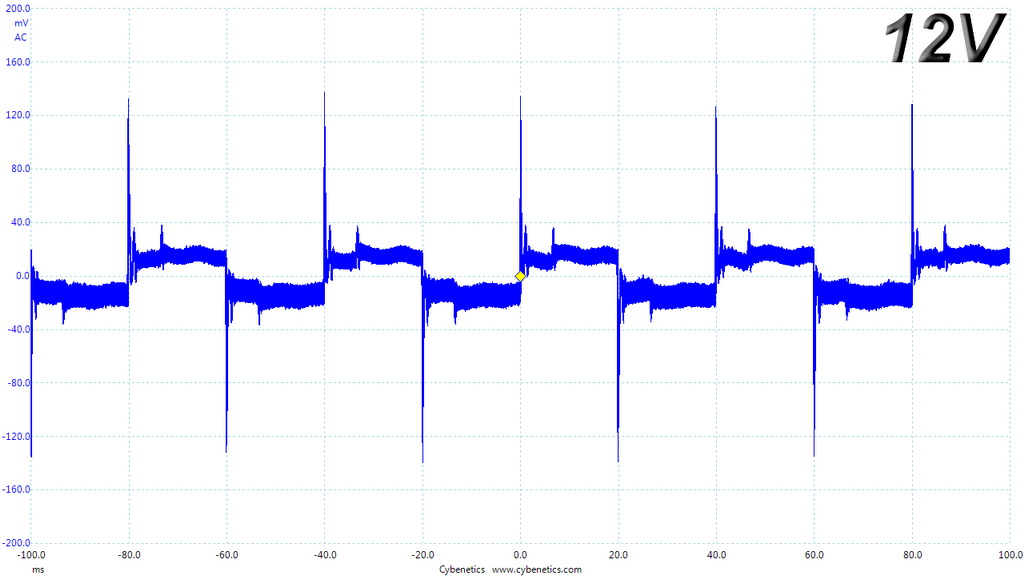

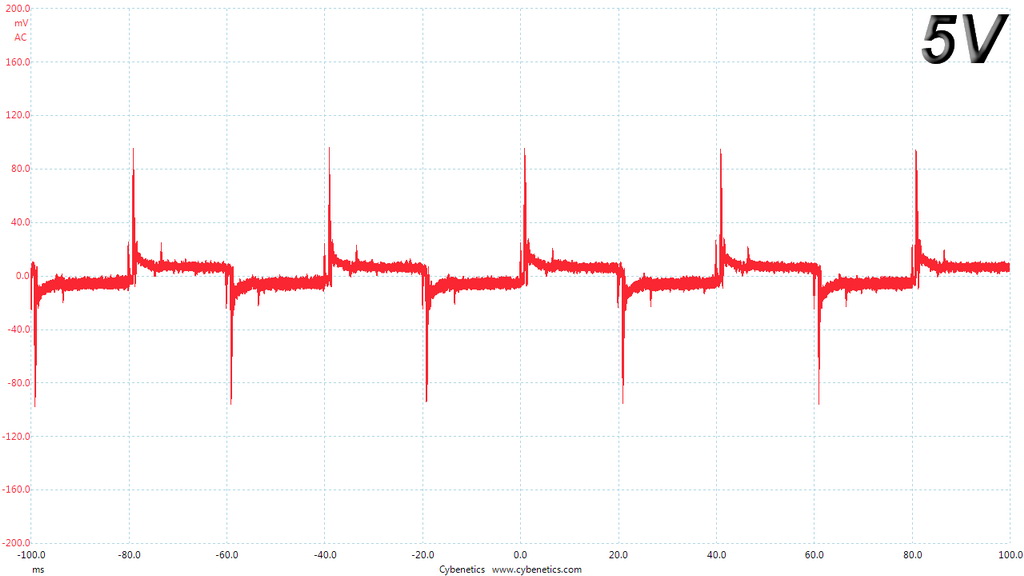

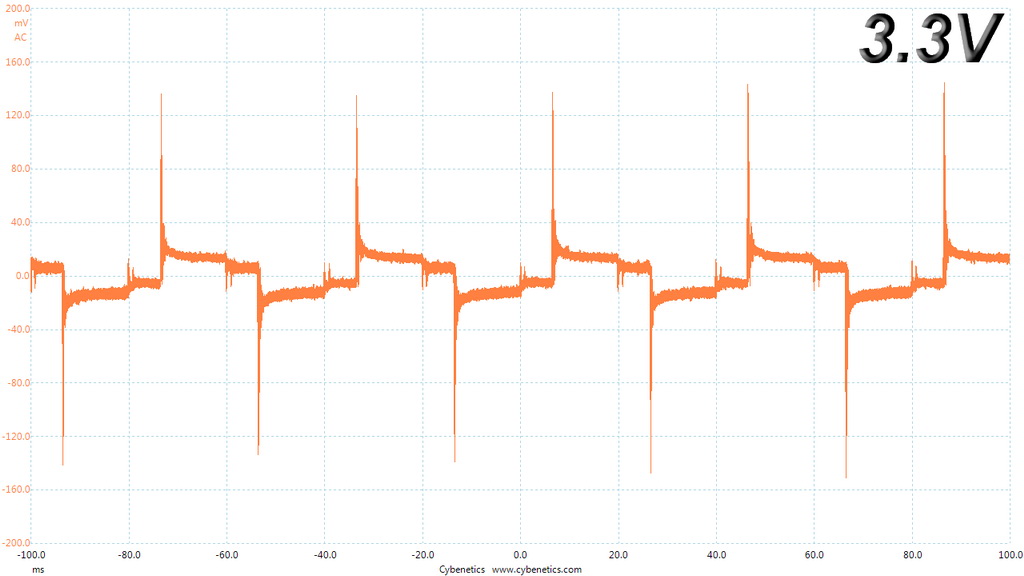

Ιn these tests, we monitor the ACP-850FP7's response in several scenarios. First, a transient load (10A at +12V, 5A at 5V, 5A at 3.3V, and 0.5A at 5VSB) is applied for 200ms as the PSU works at 20 percent load. In the second scenario, it's hit by the same transient load while operating at 50 percent load.

In the next sets of tests, we increase the transient load on the major rails with a new configuration: 15A at +12V, 6A at 5V, 6A at 3.3V, and 0.5A at 5VSB. We also increase the load-changing repetition rate from 5 Hz (200ms) to 50 Hz (20ms). Again, this runs with the PSU operating at 20 and 50 percent load.

The last tests are even tougher. Although we keep the same loads, the load-changing repetition rate rises to 1 KHz (1ms).

In all of the tests, we use an oscilloscope to measure the voltage drops caused by the transient load. The voltages should remain within the ATX specification's regulation limits.

These tests are crucial because they simulate the transient loads a PSU is likely to handle (such as booting a RAID array or an instant 100 percent load of CPU/GPUs). We call these "Advanced Transient Response Tests," and they are designed to be very tough to master, especially for a PSU with a capacity of less than 500W.

Advanced Transient Response at 20 Percent – 200ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.195V | 12.064V | 1.07% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.053V | 4.975V | 1.54% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.366V | 3.250V | 3.45% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.024V | 4.963V | 1.21% | Pass |

Advanced Transient Response at 20 Percent – 20ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.193V | 12.033V | 1.31% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.053V | 4.966V | 1.72% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.366V | 3.219V | 4.37% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.024V | 4.975V | 0.98% | Pass |

Advanced Transient Response at 20 Percent – 1ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.194V | 12.062V | 1.08% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.056V | 4.966V | 1.78% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.367V | 3.222V | 4.31% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.026V | 4.972V | 1.07% | Pass |

Advanced Transient Response at 50 Percent – 200ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.162V | 12.066V | 0.79% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.045V | 4.966V | 1.57% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.357V | 3.232V | 3.72% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.004V | 4.935V | 1.38% | Pass |

Advanced Transient Response at 50 Percent – 20ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.162V | 12.029V | 1.09% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.046V | 4.948V | 1.94% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.357V | 3.204V | 4.56% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.005V | 4.911V | 1.88% | Pass |

Advanced Transient Response at 50 Percent – 1ms

| Voltage | Before | After | Change | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12V | 12.162V | 12.021V | 1.16% | Pass |

| 5V | 5.047V | 4.953V | 1.86% | Pass |

| 3.3V | 3.357V | 3.204V | 4.56% | Pass |

| 5VSB | 5.005V | 4.921V | 1.68% | Pass |

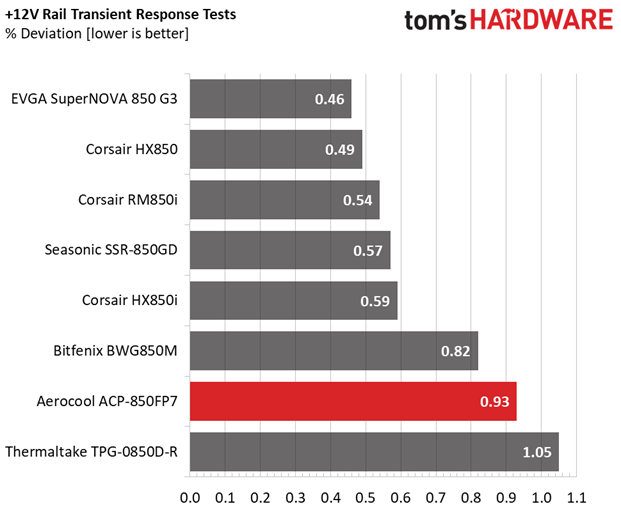

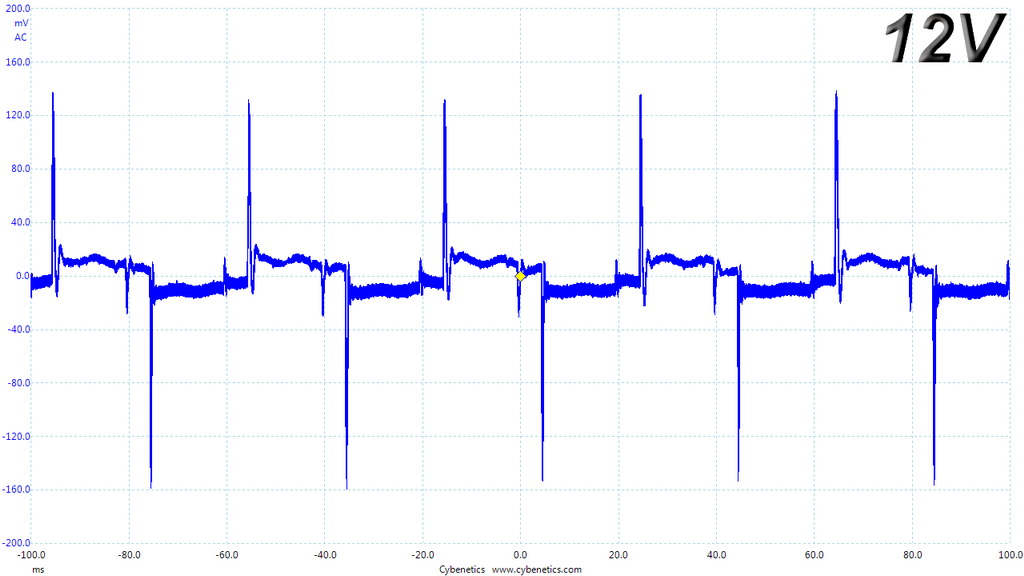

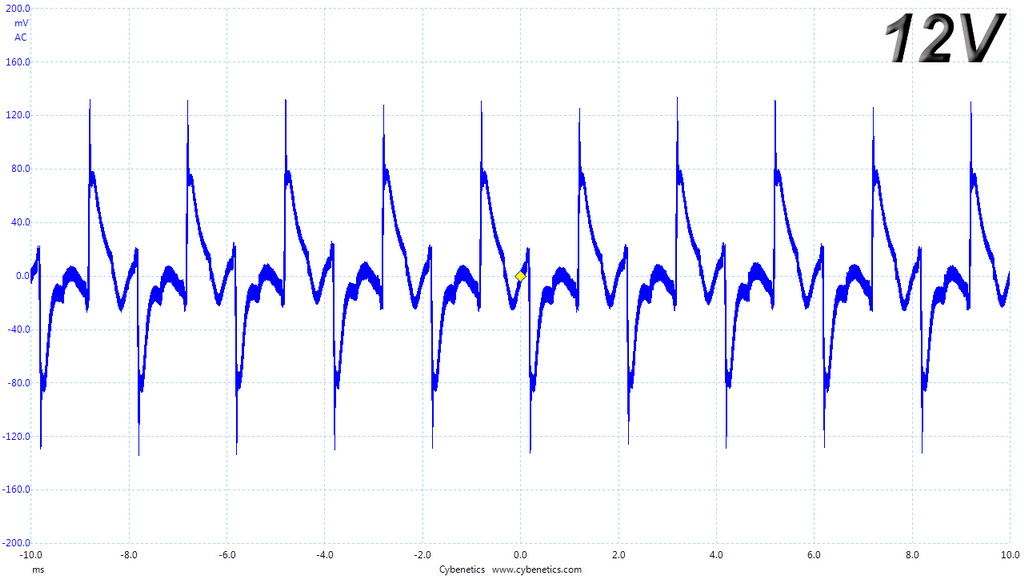

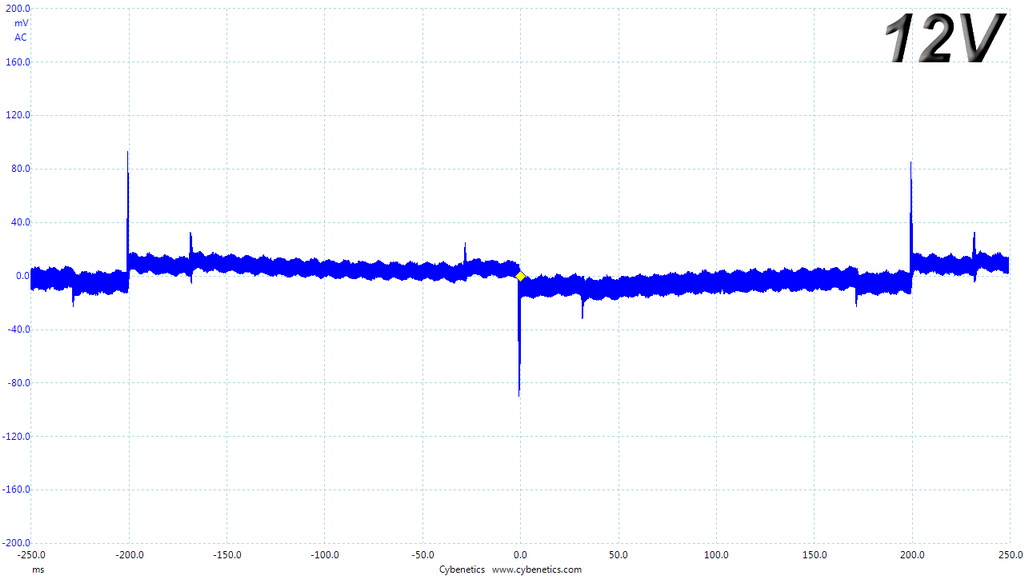

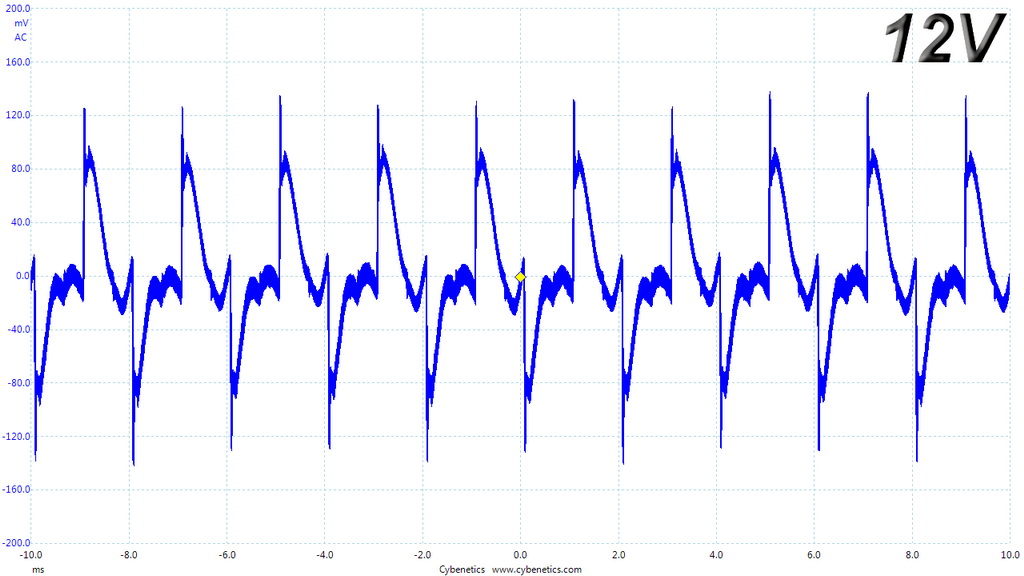

Transient response on the +12V rail isn't among the best we have seen, though it's decent.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

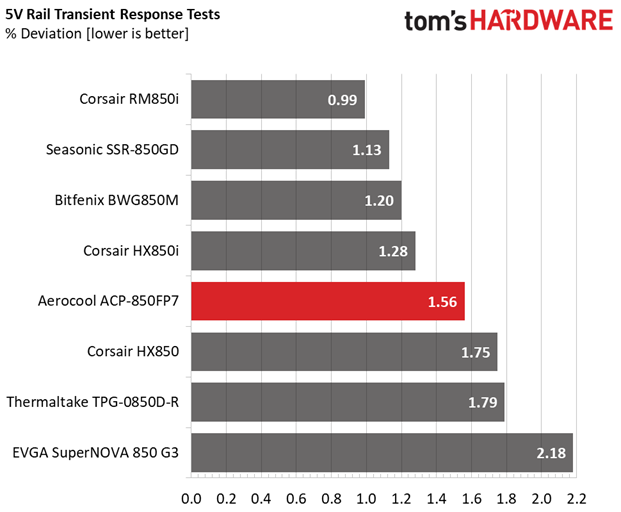

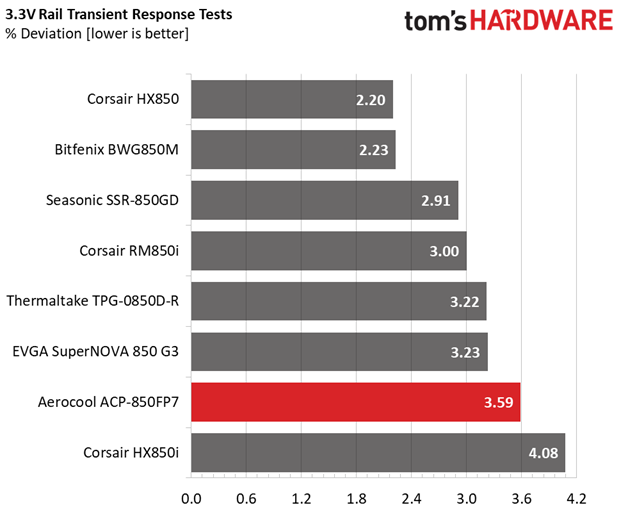

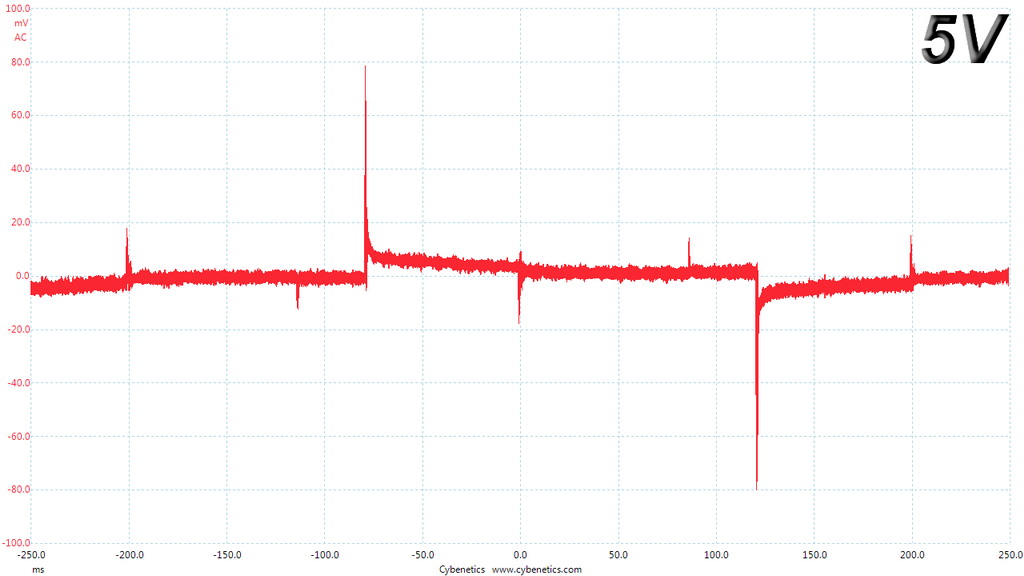

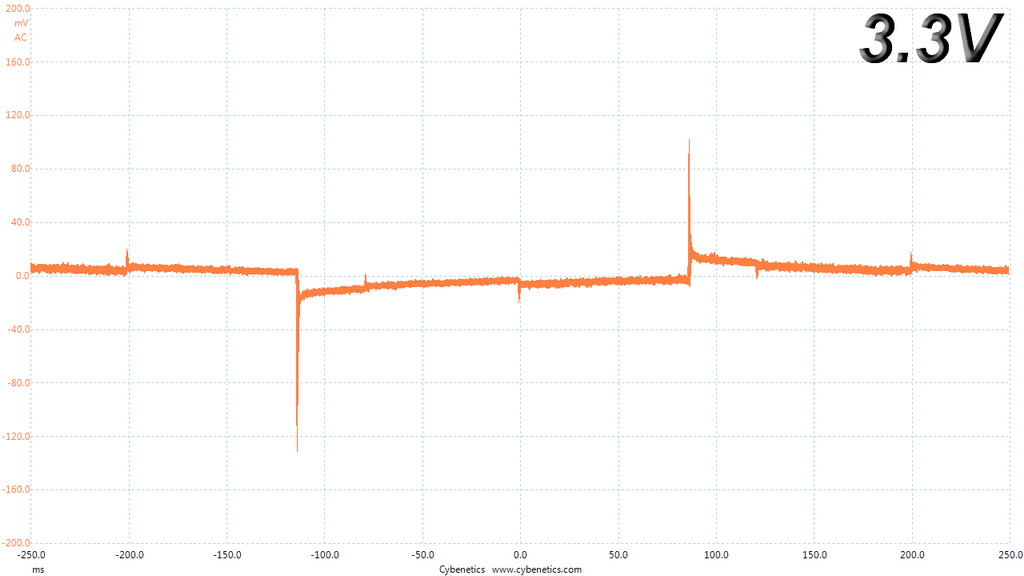

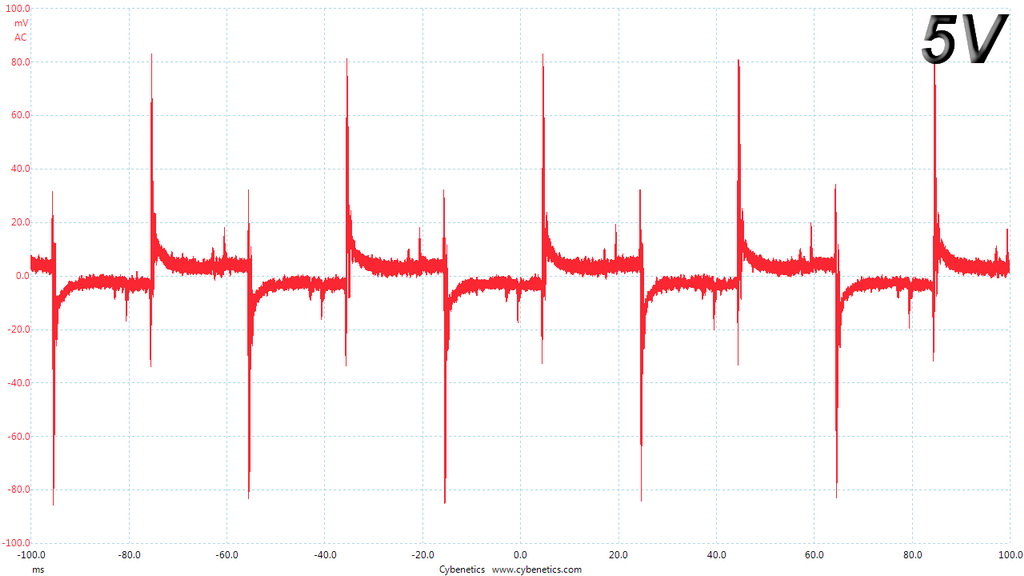

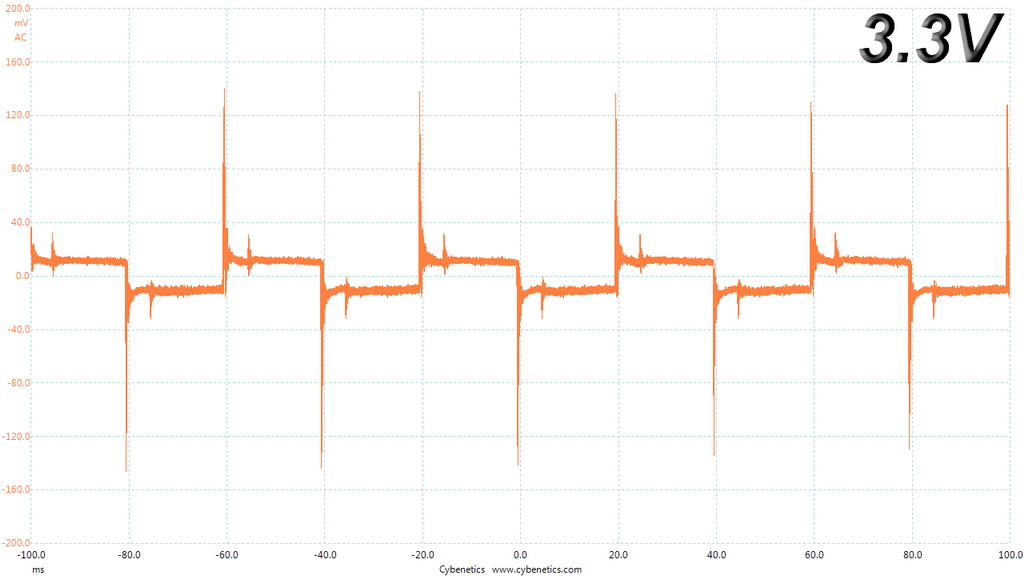

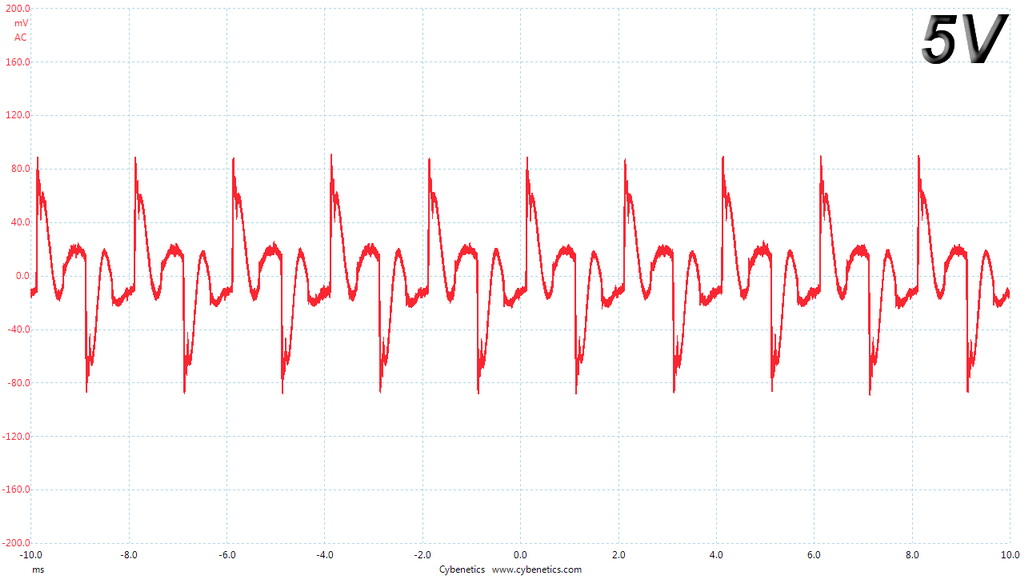

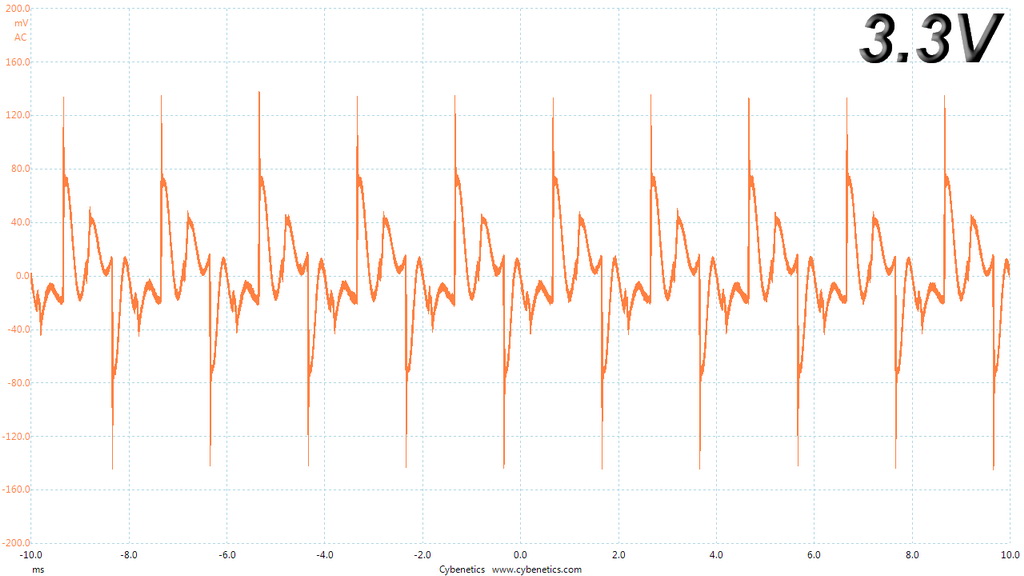

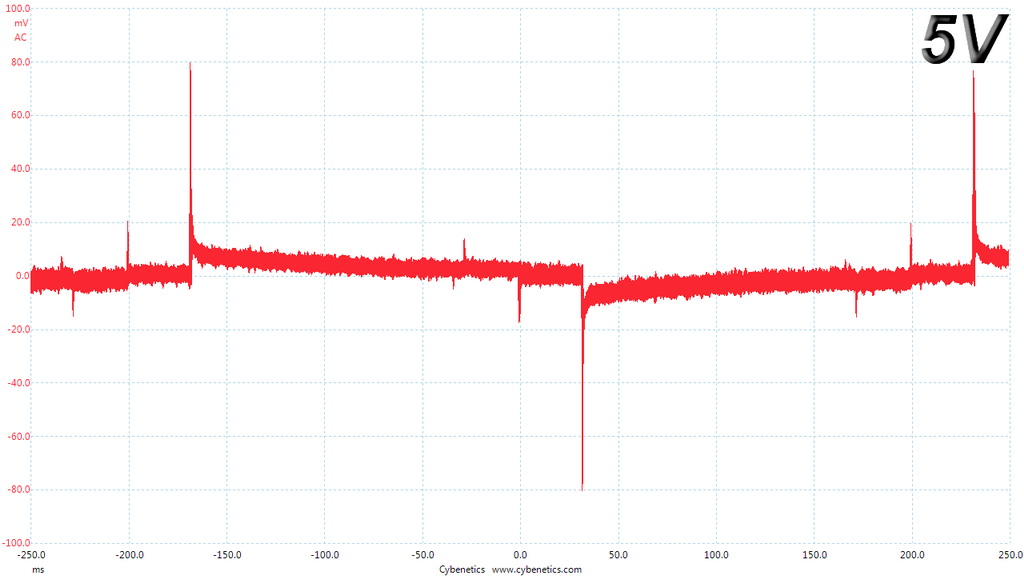

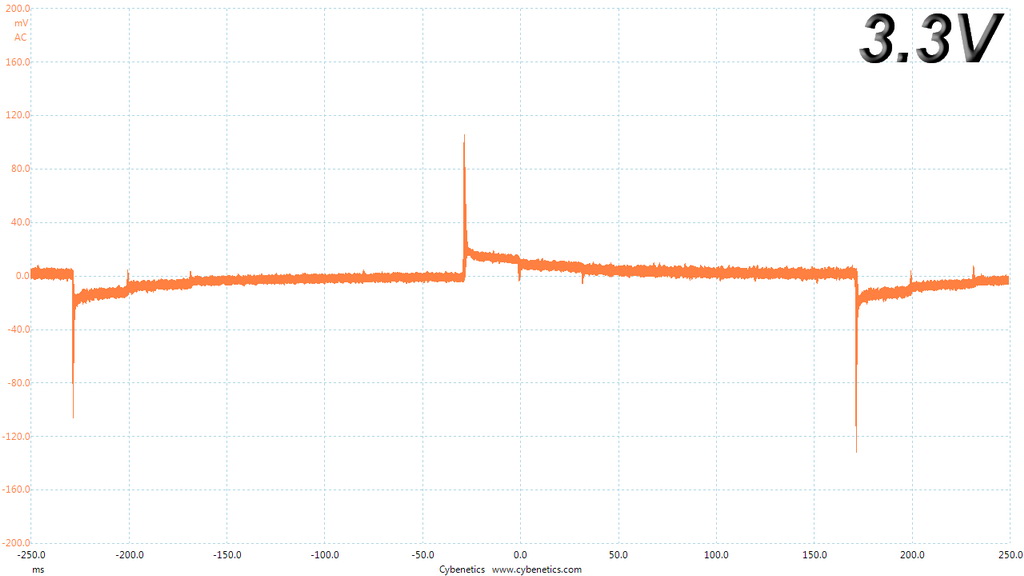

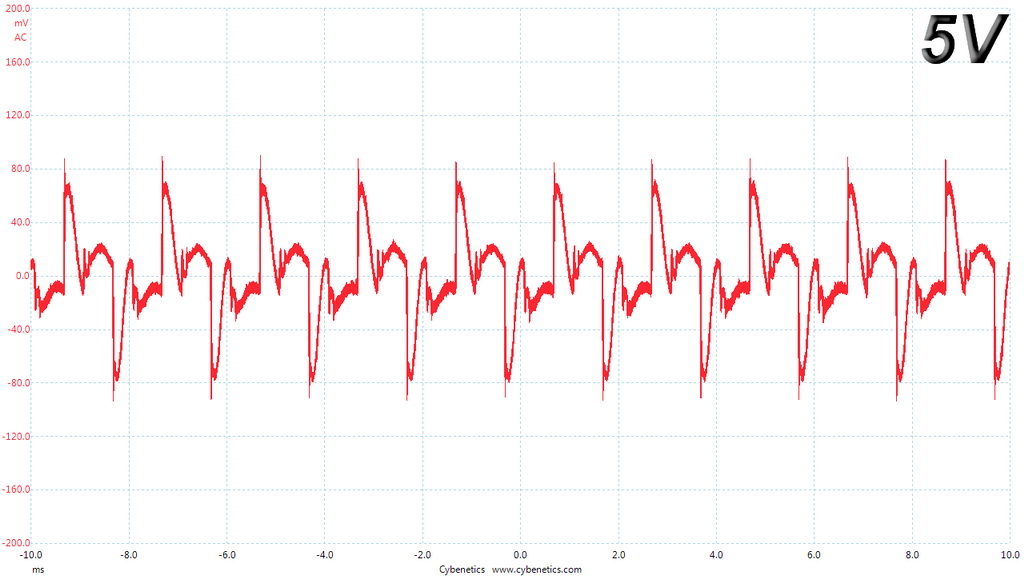

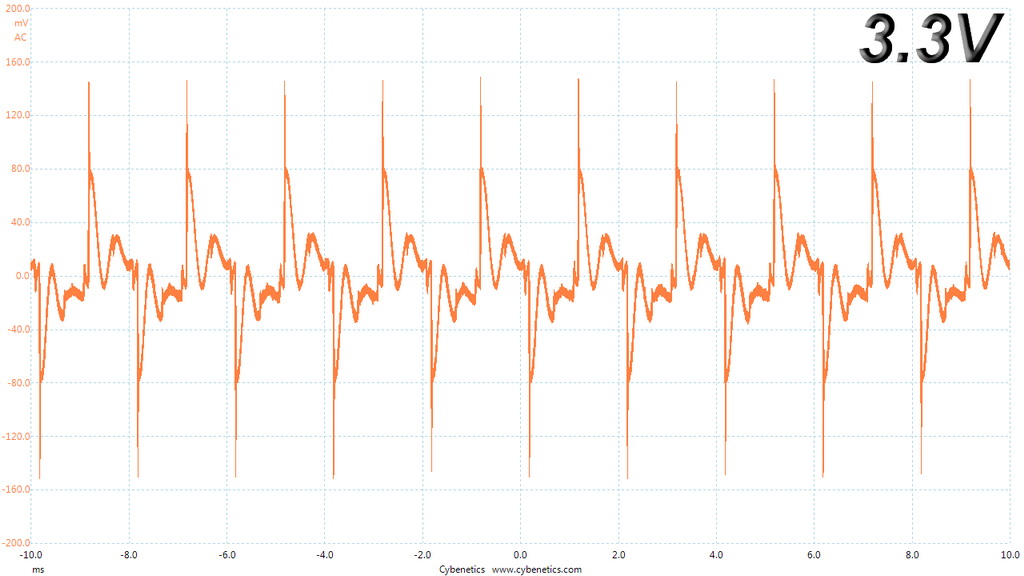

Our measurements at 5V and 5VSB are pretty good, and there's definitely room for improvement at 3.3V.

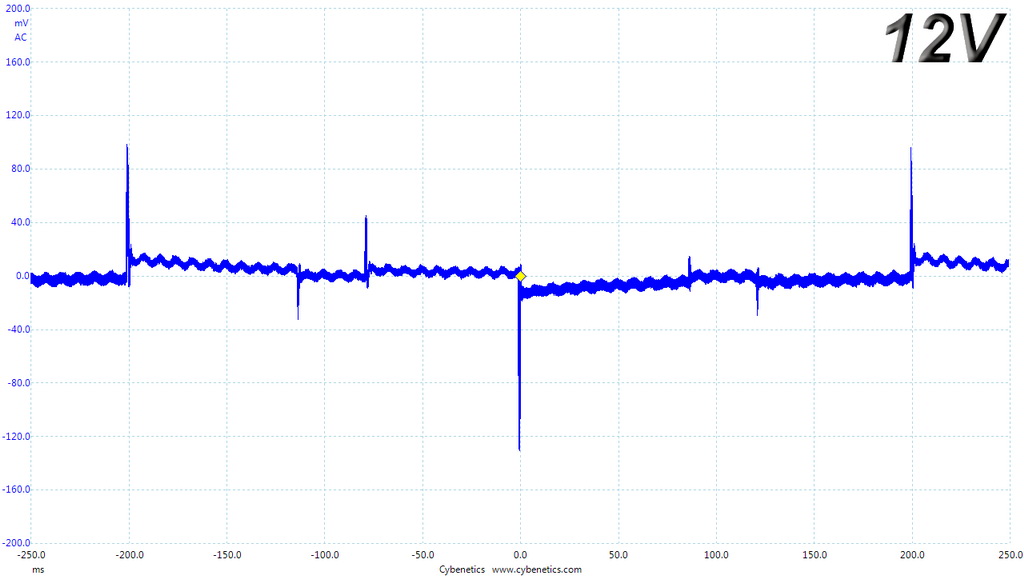

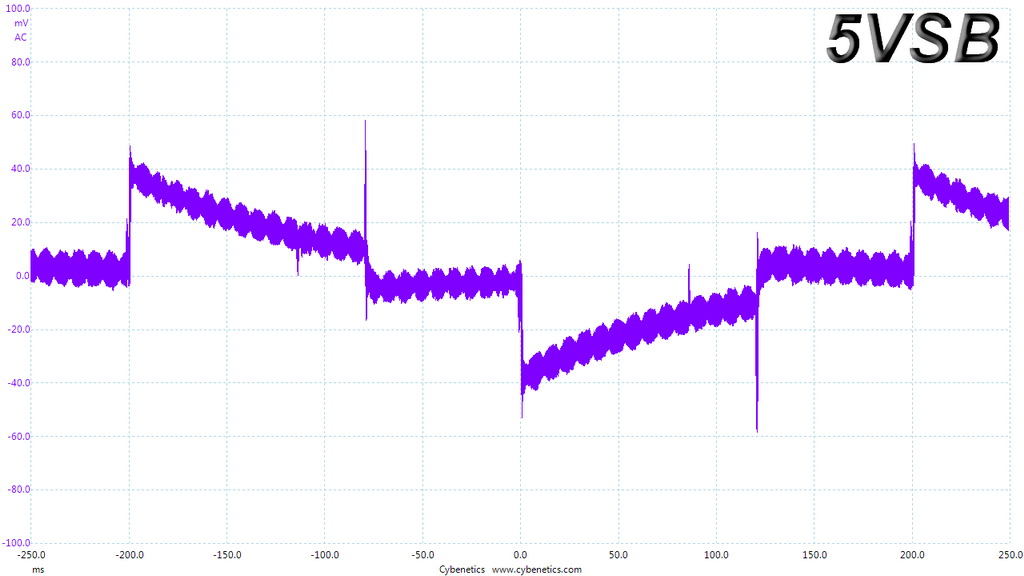

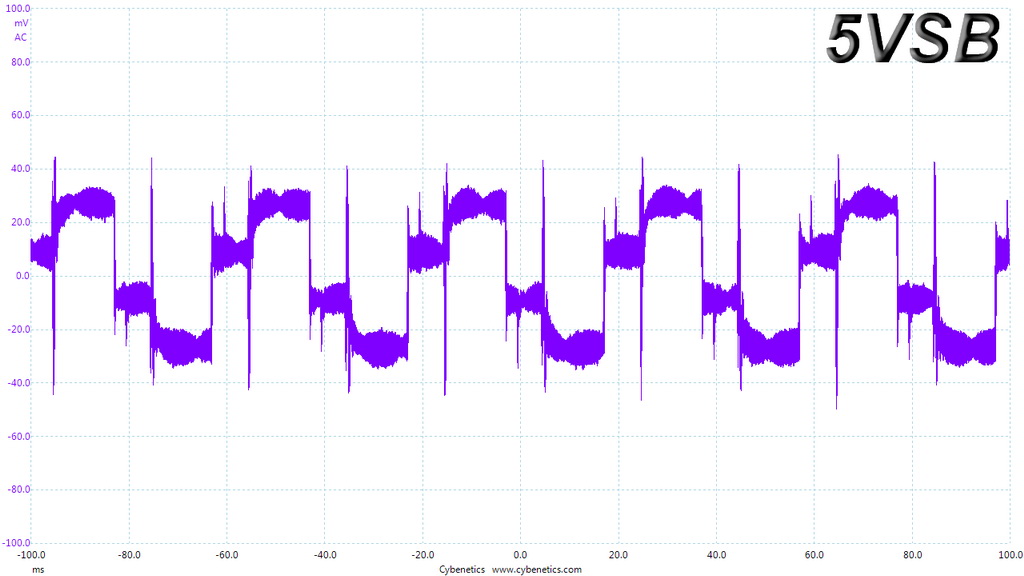

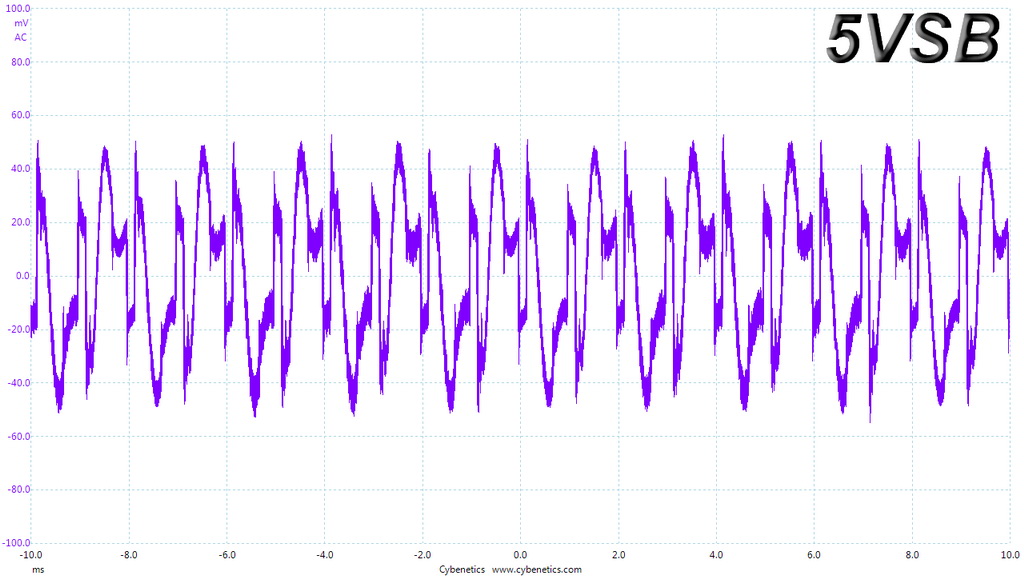

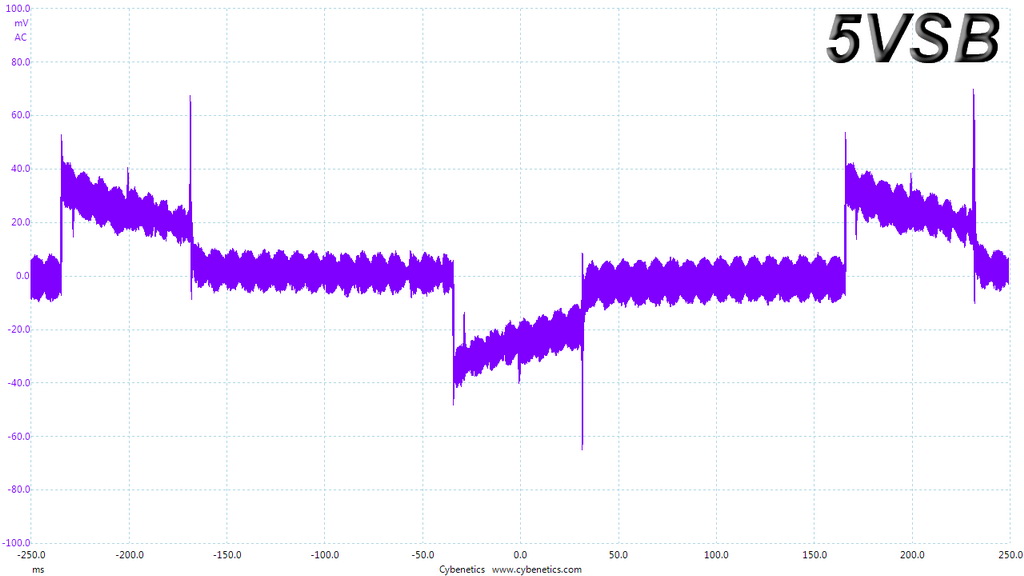

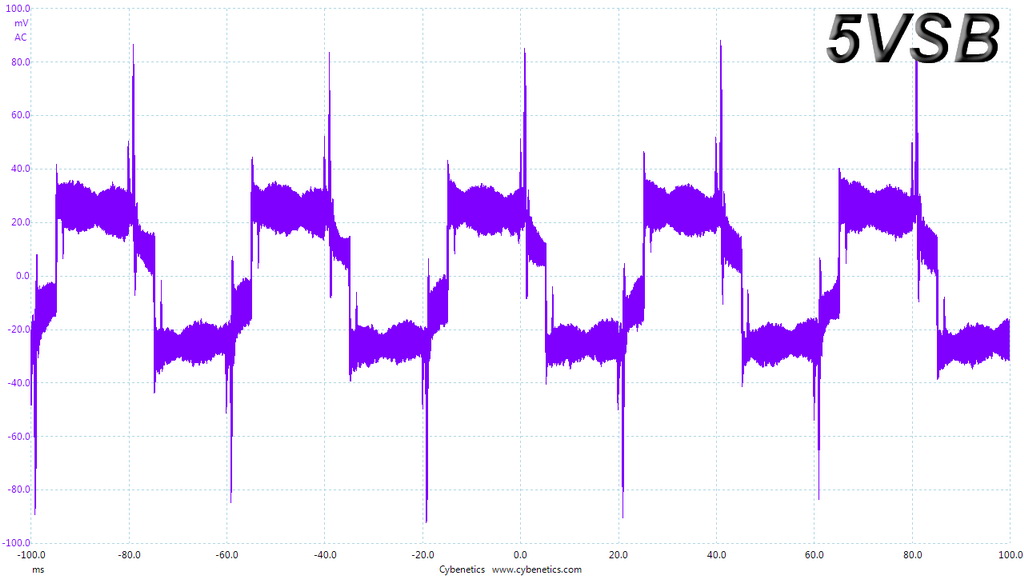

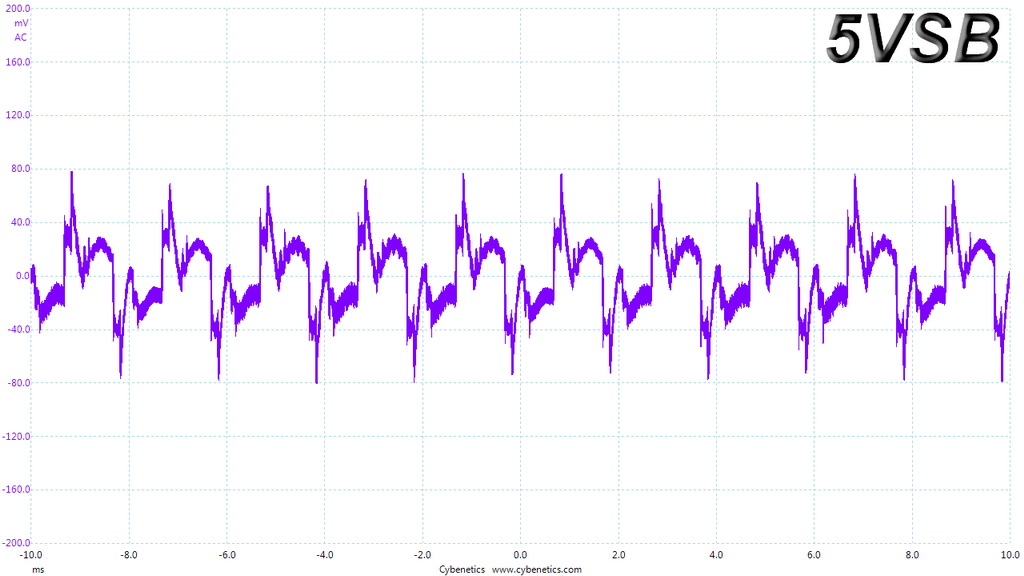

Here are the oscilloscope screenshots we took during Advanced Transient Response Testing:

Transient Response At 20 Percent Load – 200ms

Transient Response At 20 Percent Load – 20ms

Transient Response At 20 Percent Load – 1ms

Transient Response At 50 Percent Load – 200ms

Transient Response At 50 Percent Load – 20ms

Transient Response At 50 Percent Load – 1ms

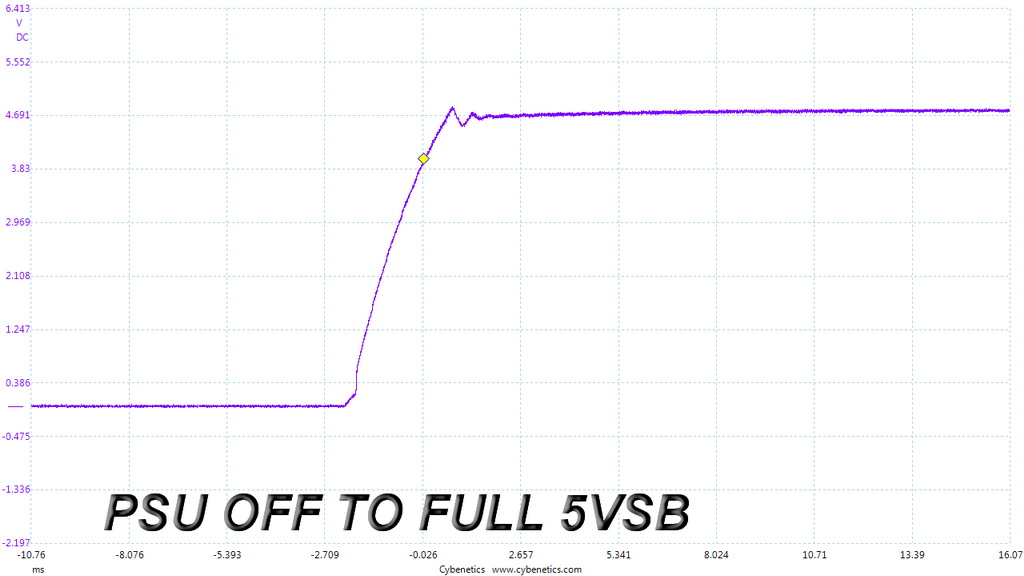

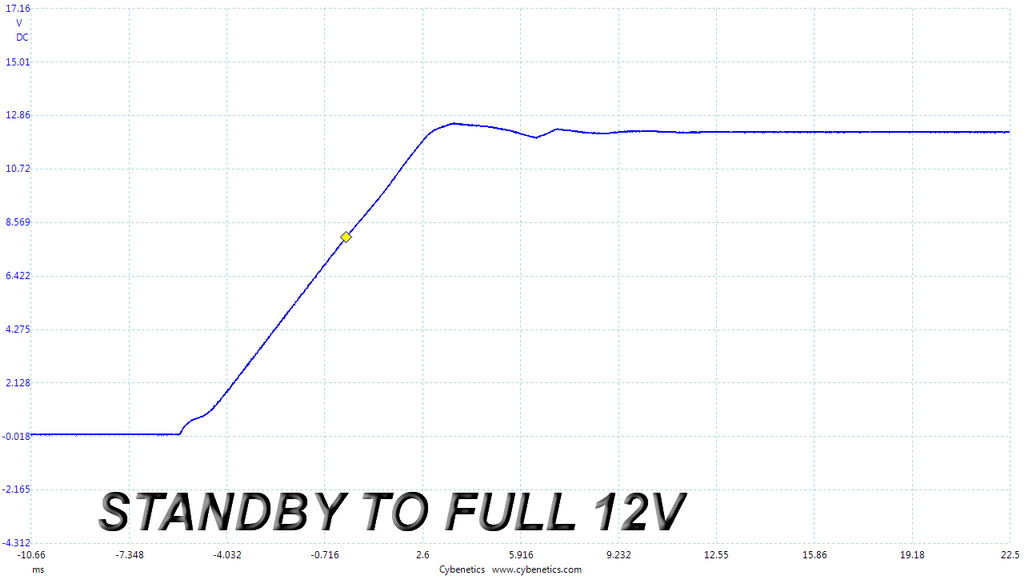

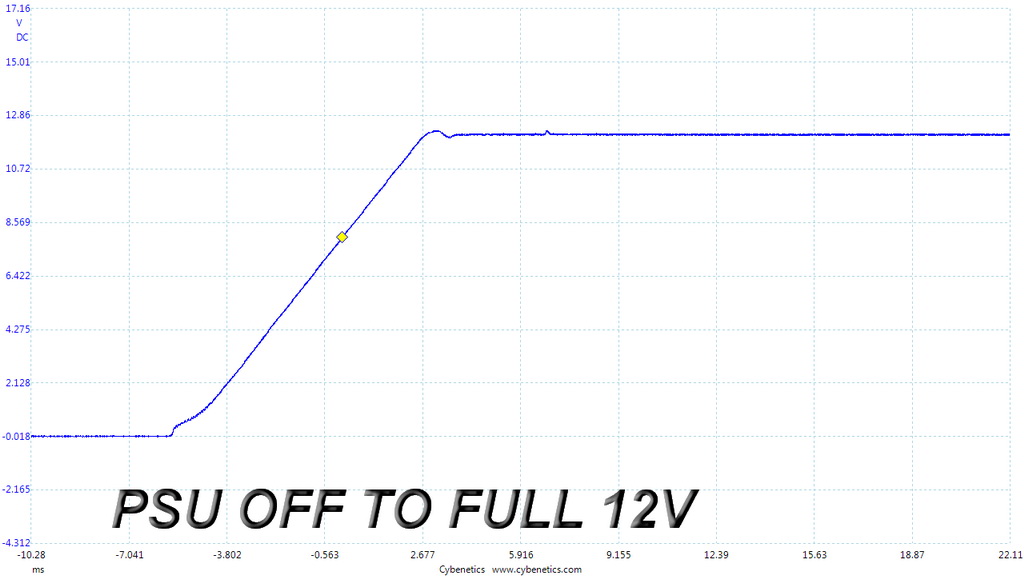

Turn-On Transient Tests

In the next set of tests, we measured the ACP-850FP7's response in simpler transient load scenarios—during its power-on phase.

For our first measurement, we turned the ACP-850FP7 off, dialed in the maximum current the 5VSB rail could output, and switched the PSU back on. In the second test, we dialed the maximum load the +12V rail could handle and started the 850W supply while it was in standby mode. In the last test, while the PSU was completely switched off (we cut off the power or switched the PSU off), we dialed the maximum load the +12V rail could handle before switching it back on from the loader and restoring power. The ATX specification states that recorded spikes on all rails should not exceed 10 percent of their nominal values (+10 percent for 12V is 13.2V, and 5.5 V for 5V).

There was a small voltage overshoot at 5VSB, and we didn't see any spikes during the other two tests.

MORE: Best Power Supplies

MORE: How We Test Power Supplies

MORE: All Power Supply Content

Current page: Transient Response Tests

Prev Page Cross-Load Tests & Infrared Images Next Page Ripple Measurements

Aris Mpitziopoulos is a contributing editor at Tom's Hardware, covering PSUs.

-

vgray35 And lo and behold another elephant enters the room, except here we have a touch of pesky arrogance thrown into the mix, where $165 admits a product without fan failure and 12V over current protection. But that is really not the least of the woes. It is high time Tom's Hardware calls out these manufacturers for producing inefficient power supplies, and stop this nonsense of labeling as high efficiency a peak of 92% (88% at full load), and certainly fanless mode is not difficult to achieve and should be part of all PS and hardly rises to the level of a unique feature. If these features are missing then the PS is not qualified for the use in computers – period. Let us not accept mediocrity as acceptable, and it is high time PS become true commodity level components. Fundamental Power Supply improvements look for increased efficiency and reduced cost through improved Power Electronics Topologies, and the fact of the matter is modern power supplies are grossly inefficient, and are largely founded upon old Buck converter technology and its derivatives (forward, bridge, etc), including the resonant variants like the LLC resonant converter based on half/full bridge drivers. Despite great strides made over 60y these variants still belong to the same family of topologies, insisting on inserting an air gap into an AC-inductor to a convert it to a DC-inductor so it passes a large DC current, and hard switching of large currents. Even the various resonant and zero current switching variants have not delivered on ultra high efficiency, or high performance step response settling times. These are not bold claims as I will attempt to describe below, and the common element in these topologies limiting performance is largely inductive energy storage – the infamous ferrite cored inductor (i.e. transformers with air-gaps are not true transformers, but energy storage devices). What we have is 850W accompanied by 120W of waste heat at full load (~88% eff.) and 32W waste heat at 50% load (~92.5% eff.), when 98% eff. could yield 17W of waste heat at full load. So why are manufacturers asleep at the switch? What about an ATX PS with a length of 50mm instead of 160mm @ 650W where temperature never exceeds 20 deg above ambient at full load, with motherboard VRM sporting 99% eff. and 3 GPUs with VRMs at 99% efficiency? This is not pie in sky rhetoric here as shown below, and power supplies could come to < $40 sporting ultra high efficiency for 1kW units.Reply

The Buck converter was invented during the 1950's and improvement in high frequency switching devices has largely hidden the failings of this topology, including its various variants, and despite improvements a lot of waste heat still accompanies the power conversion process. Looking at the limiting factors in this process reveals without exception modern topologies use the air-gapped inductor for energy storage and power transfer, which is the root cause of bad efficiency, large size and poor energy transfer capability. The hope of multi-Mega Hertz switching to reduce size has been proven futile, as this brings with it reduced operating core flux density at elevated frequencies, increased core losses and switching losses, which offset much of the championed size reductions. Several problems underpin inductive energy storage topologies, in that currents are hard switched causing EMI noise that must be filtered out, and resonant topologies that reduce switching losses have not alleviated the underlying issue of inefficient inductive energy storage, such as for example the LLC resonant converter. There is much more that could be said on this topic, but suffice it to say 90% efficiency is the norm here, with slightly better efficiency obtained only at the price of increased size. But yet new topologies are now available that will allow the Buck converter and its derivatives to be retired - new topologies that have already been invented over the course of the last decade. Several new elements have emerged that now offer efficiencies in the 98% to 99.5% range which reduces waste heat by over 80%. Why then are we still plagued by the poor performance that derives from inductive energy storage?

First and foremost capacitive energy storage is by far more compact by 2 orders of magnitude, and coupled with a new PWM-resonant switching topology that allows single cycle response settling times, and zero current switching, increases dramatically efficiency and overall performance with >70% reduction in size. An inductor and capacitor resonant network is still in play here, but also introduces a new hybrid resonant switching and resonance scaling, which allows resonant capacitance to be increased by 2 orders of magnitude, with a corresponding reduction in the size of the inductor component, and what's more this is now achievable at 50kHz frequency instead of MHz frequencies; which saves considerably on switching losses which still maintaining minuscule size. Power supply size reduction approaches >70% in eliminating ferrite cores, and >80% in large heat sinks with the advent of ultra efficiency, with a corresponding cost reduction. For example the inductor has no ferrite core (i.e. air-cored) and becomes a 5 mm length of copper wire, while a bank of ceramic chip capacitors in parallel are minuscule compared to today’s air-gapped DC-inductors. These new technologies also offer reduced operating flux densities for high frequency isolation transformers, which operate purely as AC transformers with no need for air-gaps to pass DC current. Here is a link to an article describing some of these new elements.

Ultra high 99.5% peak efficiency

http://www.powerelectronics.com/power-management/step-down-dc-dc-converter-eliminates-ferrite-cores-50khz-enabling-power-supply-chip

See section on: 98% Efficient Single-Stage AC/DC Converter Topologies

http://www.power-mag.com/pdf/issuearchive/46.pdf

An ATX PSU at 98% efficiency with a single stage PFC and DC-DC converter, generating much less EMI noise than today’s PSU is achievable. A motherboard VRM at 99% efficiency using a single stage for each of the CPU, GPU, and memory components, with response settling times an order of magnitude faster than the multi-stage buck converters, is achievable. The GPU using a similar VRM, net waste heat within a computer case is reduced by over 80%. Platinum and Titanium power supplies do not provide ultra high efficiency >98% and are monstrosities in terms of size. The ability to eliminate ferrite cores even at 50kHz is a panacea of Power Electronics Converters. An 850W PS driving a system with 3 GPU could be reduced to 600W, with 3*25W less GPU waste heat, 70W less ATX PS heat, 60W less motherboard VRM waste heat – a total of 200W of waste heat saved at full load. There is really no reason why memory modules could not incorporate their own VRM on each memory module, so small is this new switching topology. The entire VRM is now just a single chip incorporating controller and power stage.

The PS efficiency standards are way out of date, and manufacturers are not sufficiently diligent about advancing the art, and so surely we should object when they present us with these high priced monstrosities. On does not need better standards to adopt improved power electronics topologies.

Sorry for such a long post, but somebody had to speak up on this issue.