Bloody B188 8 Light Strike Keyboard Review

Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

Debunking Switch Claims

The eight Light Strike switches on the B188 are the heart of its appeal, and they’re what the product page and box advertising focuses on most of all. In contrast to most contact-based keyboard switch designs out there, such as Cherry, Gateron, Greetech, Kailh, and so on, Bloody’s Light Strike keyboards use contactless switches. This means that the switch parts don’t have to come into contact with each other, unlike Cherry MX and similar switches where the slider pushes against a set of movable contacts. The upshot here is that the elimination of this rubbing motion can make for a switch that gives a much smoother keyfeel.

Optical switches are also much more durable than contact-based switches. Whereas Cherry MX and other contact-based switches claim a lifetime of 20-50 million keystrokes per key, the Light Strike switches are tested to 100 million keystrokes. Although we suspect the lifetime of optical switches could probably be significantly in excess of that, Bloody was not able to answer which part fails first, or what the prospects of the switches were after 100 million presses.

The most advertised feature of these switches, however, is the “world’s fastest key response” which “can never be surpassed.” According to Bloody’s product page, there are two factors behind this: a fast (0.2ms) key response, and a high actuation point of 1.5mm.

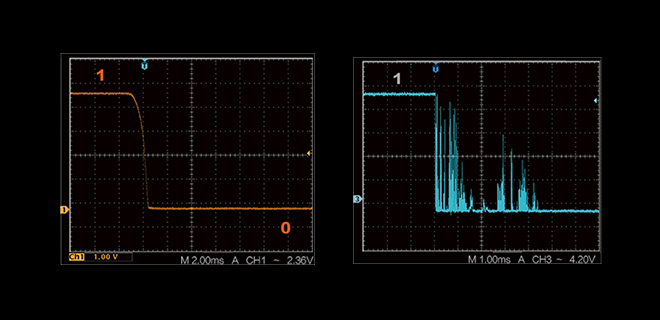

Bloody shows a pretty graph of a keypress on the Light Strike switches versus that of a “traditional metal” keyswitch, with the former showing a smooth transition lasting 0.2ms (although the graph axes are missing) while the latter is showing massive signal spiking over what Bloody claimed to be an 18-30ms interval. This is caused by so-called “contact bounce” which is basically a short period where the contacts rapidly open and close — a well-established and known phenomenon in metal contact switches.

If a switch “bounces” for 30ms, you’d need at least an equal amount of time for the keyboard to stop registering keypresses after the initial event (called “debouncing”), or the keyboard would start to output keypresses like crazy. Because the Light Strike switches register after just 0.2ms, there is “zero input lag,” which makes the switch 30ms faster than other switches - or so Bloody says. Moreover, the higher actuation point (1.5mm compared to 2.2mm on “traditional metal switches”) means the switches actuate some 30-odd percent earlier through the keypress.

There are several problems with these claims. The most glaring one is that the benchmark of 18-30ms contact bounce is absolutely unheard of in any metal contact switch on the market, now or in the past. Cherry MX and other designs specify a bounce time of <5ms, which has been the standard debouncing period used on keyboards for decades. If a switch that bounced for 30ms was present in any such keyboard, it would register five or six times for each individual keypress (a phenomenon known as “chattering”). Obviously this makes no sense at all.

Moreover, Bloody was not able to answer the question of which competitor’s switch was used for benchmarking, nor what procedure was used for this testing, how many switches were tested to obtain this graph, how consistent these results were, and whether the data shown was an average or a single keypress. Furthermore, upon closer inspection, it’s obvious that the “traditional metal” graph is not a keypress, is of an extremely unusual design, or has gone through data manipulation, as the switch goes from open to closed rather than the other way around.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

The notion that shallower actuation depth delivers faster response time also suffers from a number of flaws. First of all, the benchmark 2.2mm of the traditional switches does not correspond to that of most current linear switches such as Cherry MX, Gateron, or Kailh (which are 2.0mm), which means the actual actuation difference is considerably less than what is advertised. Again, Bloody could not provide us with what switch this was benchmarked against.

Second, although Bloody implied this alleged speed increase is due to the optical action of the Light Strike switch, it’s not - it’s simply due to the placement of the actuator and has nothing to do with the mode of operation. For example, Cherry recently brought out its MX Speed Silver switches, which have an actuation distance of only 1.2mm, and with some tooling readjustments, it would be trivial for Cherry to make a switch that actuates far earlier than that.

The disappointment here is that this sort of marketing detracts from what is actually an interesting and beneficial switch design. According to Bloody, the keyboard’s effectively analog action does not warrant the implementation of a debouncing delay (a minor revolution in keyboard innovation by itself), which, coupled with the high polling rate of 1,000Hz, does mean that the keyboard would actually register quicker than contact-based keyboards.

The difference would be significantly smaller than Bloody has suggested, and it’s debatable whether you could even detect the difference in practice, but it’s a difference nonetheless - and a difference some gamers who want nothing but the fastest possible technology available might want to pay for. Although 1.5mm is not a particularly high actuation point, especially for a “fast response” switch, a higher actuation point does theoretically increase key response - again, if only minimally. The extreme durability of the switches is glossed over so much that it appears Bloody didn’t bother to test beyond 100 million keystrokes to see how far its switches could really go. Finally, regarding the potential smoothness of the keyfeel (which is actually rather nice, we might add), there is not a single word.

It should be noted that although the inclusion of only eight optical switches in a 101-key keyboard does reduce the price, you’ll be limited by your choice of control scheme if you want to reap the benefits of the optical switches. As the other switches are simple rubber domes, the vast majority of the keyboard isn’t even mechanical.

Not only is this not what most people would buy a mechanical keyboard for, many people might find having linear switches on a few keys, and tactile switches for the others, quite distracting. Further, the advantage of the abnormally long switch lifetime of the eight optical switches is also meaningless if the majority of the board will wear out in just a fraction of that time. Worse, the product description is sufficiently vague that many potential buyers won’t clue on to the fact that only eight of the switches are optical, and there is no mention at all of the rest of the board being based on rubber domes. (Bloody does sell keyboards in which all keys are LK Optic switches, however.)

MORE: Best Deals

MORE: How We Test Mechanical Keyboards

MORE: Mechanical Keyboard Switch Testing Explained

MORE: All Keyboard Content

Current page: Debunking Switch Claims

Prev Page Introduction & Specifications Next Page Lighting & Key Caps-

ZRace Chinese marketing is just ridiculous. Apparently nobody cares what the marketing says about a product over there, so they just threw together some random keyboard stuff to appeal western clients (that's at least how it reads).Reply

In the end, I'd very much like a review of a fully optical keyboard, as it seems those might be quite interesting! -

shrapnel_indie ISO or modified ISO isn't the key layout I prefer. (Give me an ANSI layout.) I think, for me though, the biggest issue for it (besides layout preferences for me) is that this specific model is mostly (vast majority) membrane keys, I like the price, but if I hunt hard enough, I can get a cheap fully mechanical keyboard.Reply -

hauser01 I have both the BLOODY B188 and the corsair K70 RGB red mechanical switches .The Bloody B188 is much more responsive (faster response) WASD keys than Corsair in game. You can actually see and feel the difference . For normal every day typing computing i see no difference.I purchased 2 B188 on sale for $10.00 each.It has been 8 months and the B188 works as new i play online 12 to 15 hours a day.I recommend the B188 for gamers every were as it takes a beating and still works great. I have Razer ,corsair and logitech i would buy this keyboard over those companies any day. I as well have the Bloody V8 mouse and it is awesome as well. I no longer use my G502 Proteus core its a good paper weight now .Reply -

Blazer1985 -Honey where is your mouse?Reply

-It's right next to my bloody keyboard

-Ok... calm down... -

grumpigeek There has been a lot of focus here lately on mechanical keyboards.Reply

I am not a gamer but would like a simple standard, full size backlit keyboard.

I don't need a wireless keyboard and want the F1 to F12 keys illuminated as F1 to F2, not just the alternative functions like the Logitech K740 does.

The Logitech K800 looks OK but seems very expensive.

I was wondering if there are any other options. -

cryoburner Reply19965878 said:I purchased 2 B188 on sale for $10.00 each.It has been 8 months and the B188 works as new i play online 12 to 15 hours a day.

Welcome to the site, person who just joined the other day and will probably never be heard from again. : P

I do question whether someone who games for 12 to 15 hours a day would use a keyboard they got for $10 though. Also, these aren't normally $10 keyboards. At $10, they could be a great value for a rubber dome keyboard with some enhanced gaming keys. Even at around $25 they might be an alright product for someone looking for an inexpensive gaming keyboard. The problem is that this keyboard is currently priced $40 on Amazon, with $80 listed as its supposed MSRP, and on Newegg its priced $55, with a $100 MSRP, and those prices are a lot less competitive considering that most of the keyboard isn't even mechanical. You can find quite a few fully-mechanical keyboards on Amazon with cherry-clone switches for around $40 or less, so paying that much for just a handful of mechanical keys on an otherwise rubber-dome keyboard seems a bit much.

Also, on that topic, it would be nice to see Tom's Hardware do a roundup of cheap mechanical keyboards in the sub-$50 range. It would be interesting to see how these keyboards compare to those costing two or three times as much. Is the variance between switches substantially worse? How does the overall build quality compare? I get the impression that there may be some keyboards in that price range that are nearly as good as some of the higher-priced models. -

ZRace Reply19979230 said:Please go to the BLOODY website

While I can sort of agree with what you're saying, I don't with this part.

After all that has been said about the marketing from Bloody in this article, I wouldn't trust anything stated on their website. Better search for independent tests in this case. -

shrapnel_indie Reply19979230 said:How old are you 12 or is that your IQ .

Whoa. That was quick. Toes stepped on? He was just questioning, not attacking you personally.

Unfortunately for you, the only people I know that react like that, are usually not very mature and/or have no real facts to back up what they say. Should I accuse you of falling in that group? Should I accuse you of being a paid shill for your promotion of the BLOODY brand of keyboards? If I was to do so, not really knowing you and only basing it on two messages, wouldn't say much of me. (Personally, I don't see the Bloody B188 8 keyboard worth more than $25 USD and not worth it for my usage. But that is beside the point.) Please show me that you're better than those types.

-

rgd1101 Reply19980484 said:19979230 said:How old are you 12 or is that your IQ .

Whoa. That was quick. Toes stepped on? He was just questioning, not attacking you personally.

Unfortunately for you, the only people I know that react like that, are usually not very mature and/or have no real facts to back up what they say. Should I accuse you of falling in that group? Should I accuse you of being a paid shill for your promotion of the BLOODY brand of keyboards? If I was to do so, not really knowing you and only basing it on two messages, wouldn't say much of me. (Personally, I don't see the Bloody B188 8 keyboard worth more than $25 USD and not worth it for my usage. But that is beside the point.) Please show me that you're better than those types.

Next time just alert the mod, with the

hauser01, read the forum rule.

http://www.tomshardware.com/faq/id-2668512/tom-forums.html

http://www.tomshardware.com/forum/id-2083458/read-forum-rules-styling-posts.html