Bluetooth Technology 101

From keyboards to headsets to mobile computing, Bluetooth provides the personal wireless network needed to get around without a bunch of cables entangling our lives. Here's a close look at a key technology that empowers our mobile world.

Bluetooth Security

Bluetooth security employs three distinct features systematically: authentication between two devices, followed by acquiring permissions (authorization) and lastly, encryption. These three processes are implemented at several different layers in the protocol stack, leading to Bluetooth security being referred to as a “cross-layer function”. Security researchers at Kaspersky labs have referred to the Bluetooth specification as having “more security holes than Swiss cheese”. Based on a number of concerns, the pairing and authentication procedures have been updated with each revision.

Security begins with a potential master defining how it will be discovered, and options for connectivity:

- Silent—this mode makes the device undetectable and the device doesn’t accept any connections, though it is able to detect Bluetooth traffic. The device can’t enter either the PAGE SCAN or INQUIRY SCAN state.

- Private—in this mode, the device is able to enter into the PAGE SCAN state, but not INQUIRY SCAN. This status makes the device undiscoverable.

- Public—in this mode, the device can enter both the PAGE SCAN and INQUIRY SCAN states. It is therefore discoverable to other devices and implicitly open to connections.

The Generic Access Profile (GAP), which forms the basis of all other profiles, defines three different security modes for connections:

- Mode 1 (non-secure) allows Bluetooth communication to take place between devices without authentication or encryption of the data.

- Mode 2 (service-level enforced security) permits an Asynchronous Connection-Less (ACL) link between two devices without authentication or encryption. The connection is non-secure. Once the Logical Link Control and Adaptation Protocol (L2CAP) channel request is made, security procedures are initiated.

- Mode 3 (link-level enforced security) allows security procedures to be initiated while the Asynchronous Connection-Less link is being established.

Vulnerabilities And Mitigation

Like all communication protocols, Bluetooth is inherently vulnerable in certain scenarios. One class of vulnerability is proximal—because of the somewhat restricted range of Bluetooth radios (though, given the right circumstances, this range can be much larger than you might anticipate), the majority of attacks have to come from a source physically close to the piconet. But even with such a constraint, snooping, spoofing, denial of service attacks and drive-by malware downloads all are potentially possible.

In 2001, flaws were discovered by Bell Laboratories in Bluetooth's pairing system protocol and encryption. In 2003, Ben and Adam Laurie of A.L Digital Ltd. determined that that the technology's security could lead to the disclosure of personal info due to poor implementations. In 2004, Kaspersky Lab discovered a virus that could be spread through Bluetooth on the Symbian OS. In 2006, researchers from F-Secure and Secure Network showed how devices left in a visible state could be accessed, and that they were vulnerable to worms spread through Bluetooth.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) published a guide in 2008 for Bluetooth security in organizations. The guide outlines the possible attacks: denial-of-service, eavesdropping, man-in-the-middle, message modification and resource misappropriation, and includes a security checklist with guidelines and recommendations. Unfortunately, a number of these strategies address concerns at the manufacturer or firmware implementation level, and may not always be part of SIG’s qualification process (especially when a pre-qualified or pre-certified module is used). Do all manufacturers, especially ones producing end-products with price tags below $20, comply with up-to-date security recommendations?

Automatic authentication of Bluetooth doesn’t apply to the user, but rather to the device. If an unauthorized individual gains access to that device, security is compromised. This is mitigated by setting user-authentication requirements at the application level, or the upper layers of the Bluetooth stack, where a password must be supplied before a Bluetooth state can be changed.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

The flow of data over a Bluetooth link is bidirectional once a connection is established. An eavesdropper may not have access to the channel-hop or synchronization list, but given enough time to listen, the statistical likelihood of intercepting a packet that contains important data for the LM layer rises. Encryption is the primary mitigation strategy for this sort of attack. Then there are attacks where an eavesdropper may use a high-power transmitter and spoofed packet access codes/headers (extracted from the previously intercepted packet) to fool a receiver into rejecting the correct data packets while believing the attacker (based on higher transmit power) is the genuine source.

All of the above attacks have individual mitigation strategies. But the greatest cause of security nightmares is the scenario where a Bluetooth connection is established to a network like the Internet. Then, all bets are off. Even if the Bluetooth link and stack are secured and encrypted, support for legacy applications may require second- or third-party software to act as a liaison between the application and Bluetooth security manager, in which case the liaison itself might be compromised. When a connection is established to access infrastructure like a LAN or the Internet, and there are several layers required to establish the connection, there will be end-to-end issues that may make it necessary to implement a solution that includes Bluetooth security. Without this option, the user has to insert several passwords at different levels, and that could get frustrating.

To prevent eavesdropping in a point-to-point security setup where a master communicates with a single slave, a number of established steps are required for security to be set successfully. Setting up a Bluetooth passkey or a Personal Identification Number (PIN) enables the building of several 128-bit pass keys. The PIN is then used to create the initialization key, which is used to establish a link key that can either be a unit key or a combination key. A unit key is established in a device with limited resources, while a combination key can be established in majority of the latest devices. In the event that encryption is required, the link key is used to generate the encryption key.

For security measures to be effective (to the extent that they can be), authentication and authorization have to be implemented after establishing the Asynchronous Connection-Less (ACL) link. This is the equivalent of the GAP's Mode 2 security. The PIN, either set by the user or programmed into the Bluetooth unit found in the device, is one of the entities used to maintain high-level security. In most cases where there is no man-machine interface (MMI), the PIN is preprogrammed. A common PIN is one that two devices share. When the PIN is entered on both devices, they create the same link key and the authentication process takes place. To ensure Bluetooth security, users are encouraged not to maintain a single PIN for multiple instances of connection, or multiple devices. Pseudorandom number-generated PINs are used to establish secure links with devices that do not have a PIN. All Bluetooth devices have this feature enabled, allowing them to create 128-bit binary numbers once a request is made.

The authentication key (link key) ensures the legitimacy of other devices in the piconet. Due to its length and random generation, the authentication key makes it difficult for a third party to guess. These keys can either be used once or on a semi-permanent basis. Link keys also generate the encryption key where necessary. A device is considered trusted when it has authorization based on previous authentication to access various services. Devices are defined as untrusted when they require the user to insert a password for authorization to be granted.

On the flip side of the coin are the methods of attacking Bluetooth networks. Even the latest specification, 4.x, is vulnerable to many of these attacks, with new threats surfacing every day. The aptly named “Car Whisperer” accesses the audio stream from Bluetooth-enabled vehicles, and Redfang, the venerable Bluetooth snarfer, is joined by a number of software packages circulating openly on the Internet. There are some very high-end, polished products that were originally used for penetration testing and in-house security qualification that have since leaked to the darker shadows of the Web. Some common attacks enabled by Bluetooth’s vulnerabilities include:

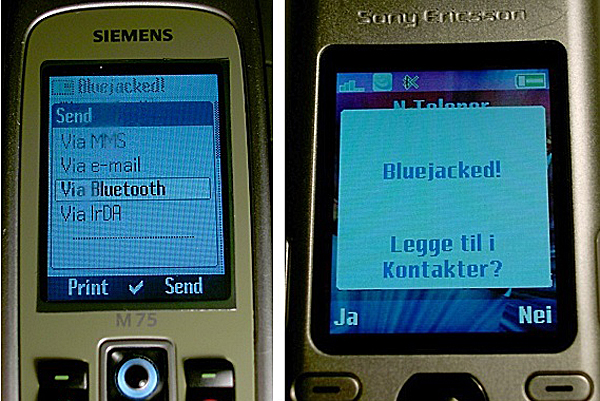

- Bluejacking—when an unauthorized source sends a short data transmission, most often some text or a message, to an unsuspecting receiver.

- Bluesnarfing—unauthorized access to information on a Bluetooth host, allowing access to user files like documents, emails and pictures. Any device in a “discoverable” state is vulnerable to this. Bluesniping, where a directional antenna is used to target Bluetooth devices over 1km away, is a specific form of Bluesnarfing.

- Bluebugging—a short-range attack where a host/master is “tricked” into assuming an unauthorized device (with its ID spoofed to look like a legitimate Bluetooth headset) for redirecting calls and messages intended for the victim.

Current page: Bluetooth Security

Prev Page The Stack And Packet Exchange Next Page Hardware, Manufacturing And Host Integration-

Fernando_engen Bluetooth is pretty much the future. I have just started developing Bluetooth Low Energy Services/profiles for specific use cases along with the application layer. Its an awesome new world.Reply -

YunFuriku Actually hearing aids with button cell batteries these days can use Bluetooth Smart or to be exactReply

bastardized proprietary version of it by Apple and GN Resound which enables them to have wireless audio streaming from

various devices with Bluetooth. Comes with expense of range naturally because hearing aids need to use low power version of it (1,5V doesn't give much choice on this )

Max 10m in ideal conditions.

Sadly, the audio stack they use is Apple Exclusive so direct connection is Apple devices only.

Non-apple devices require intermediary devices such as TV streamer or Phone Clip to other Bluetooth Capable phones. These devices are relatively cheap compared

to old FM tech hearing aids used to use where transmitter prices were measured in 0,5-2k range, about ~$200-300 at most.

Unfortunate side is that if you want to use it with non-Apple phones you'll have to have intermediary device which serves as bluetooth handsfree mic/answer/volume

buttons too beause of the audio stack which Apple won't license to others.

At the same time Apple is pushing their made for iPhone hearing aid tech to FCC to be recognised as standard.

Here's to hoping hardcore android fan like me won't have to buy iPhone as my next phone if this doesn't come to other phones directly because of silly audio stack :P

-

RIluske Is the graphic about memberships correct? I thought the article said the third tier was free to join, but the graphic has it costing the same amount as second tier.Reply -

zodiacfml I feel WiGig has a better future eventually. Bluetooth will be left to activation or turning on devices or IoT as already mentioned in the article.Reply -

DotNetMaster777 Very useful article !! bluesniping can be done over one km away wow !?!?Reply

Are there any performance tests between wifi and bluetooth ?? -

exnemesis Just give me bluetooth tech that can allow me to walk away 40-50m from my phone and penetrate better through walls and objects and still retain the quality of whatever it is I'm listening to on my phone.Reply -

TripleHeinz This is the best article I've ever read in Tom's. Didn't have a clue that bluetooth was related with Thor the god of thundervolt ;)Reply -

yasminpriya15 Welcome to Bluetooth 101. Here are the top things you need to know about Bluetooth technology.Reply

My Bluetooth doesn’t work. What do I do?

The Bluetooth SIG does not make, manufacture or build any Bluetooth products. We simply support our membership and help them to help make the best products on the market. The best way to solve your problem is to contact the manufacturer directly or start by researching solutions on the Internet.

What is Bluetooth?

Bluetooth is a global wireless communication standard that connects devices together over a certain distance. Think headset and phone, speaker and PC, basketball to smartphone and more. It is built into billions of products on the market today and connects the Internet of Things (IoT). If you haven’t heard of the IoT, go here.

How does Bluetooth work?

A Bluetooth device uses radio waves instead of wires or cables to connect to a phone or computer. A Bluetooth product, like a headset or watch, contains a tiny computer chip with a Bluetooth radio and software that makes it easy to connect. When two Bluetooth devices want to talk to each other, they need to pair. Communication between Bluetooth devices happens over short-range, ad hoc networks known as piconets. A piconet is a network of devices connected using Bluetooth technology. The network ranges from two to eight connected devices. When a network is established, one device takes the role of the master while all the other devices act as slaves. Piconets are established dynamically and automatically as Bluetooth devices enter and leave radio proximity. If you want a more technical explanation, you can read the core specification or visit the Wikipedia page for a deeper technical dive.

Are there different kinds of Bluetooth?

There are actually several “kinds”—different versions of the core specification—of Bluetooth. The most common today are Bluetooth BR/EDR (basic rate/enhanced data rate) and Bluetooth with low energy functionality. You will generally find BR/EDR in things like speakers and headsets while you will see Bluetooth Smart in the newest products on the market like fitness bands, beacons—small transmitters that send data over Bluletooth—and smart home devices.

What can Bluetooth do?

Bluetooth can wirelessly connect devices together. It can connect your headset to your phone, car or computer. It can connect your phone or computer to your speakers. Best of all? It can connect your lights, door locks, TV, shoes, basketballs, water bottles, toys—almost anything you can think of—to an app on your phone. Bluetooth takes it even further with connecting beacons to shoppers or travelers in airports or even attendees at sporting events. The future of Bluetooth is limited only to a developer’s imagination.

What makes Bluetooth better than other technologies?

The short answer is because Bluetooth is everywhere, it operates on low power, it is easy to use and it doesn’t cost a lot to use. Let’s explore these a bit more.

Bluetooth is everywhere—you will find Bluetooth built into nearly every phone, laptop, desktop and tablet. This makes it so convenient to connect a keyboard, mouse, speakers or fitness band to your phone or computer.

Bluetooth is low power—with the advent of Bluetooth Smart (BLE or Bluetooth low energy), developers were able to create smaller sensors that run off tiny coin-cell batteries for months, and in some cases, years. This is setting the stage for Bluetooth as a key component in the Internet of Things.

Bluetooth is easy to use—for consumers, it really can’t get any easier. You go to settings, turn on your Bluetooth, hit the pairing button and wait for it start communicating. That’s it. From a development standpoint, creating a Bluetooth product starts with the core specification and then you layer profiles and services onto it. There are several tools that the SIG has to help developers.

Bluetooth is low cost—you can add Bluetooth for a minimal cost. You will need to buy a module/system on chip (SoC)/etc. and pay an administrative fee to use the brand and license the technology. The administrative fee varies on the size of the company and there are programs to help startups. http://www.traininginsholinganallur.in/qtp-training-in-chennai.html

http://www.traininginsholinganallur.in/primavera-training-in-chennai.html

http://www.traininginsholinganallur.in/big-data-analytics-training-in-chennai.html