CHIPS Act Spurs $200 Billion Investments in U.S. Semi Industry

Semiconductor industry is reviving in the USA, says SIA.

Although developers and makers of chips are yet to receive grants enabled by the CHIPS and Science act, its announcement and subsequent enactment have already attracted some $200 billion of private investments in the U.S. semiconductor sector, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association, a lobbying group for the industry. The new projects will impact both chip production and electronics manufacturing in the USA.

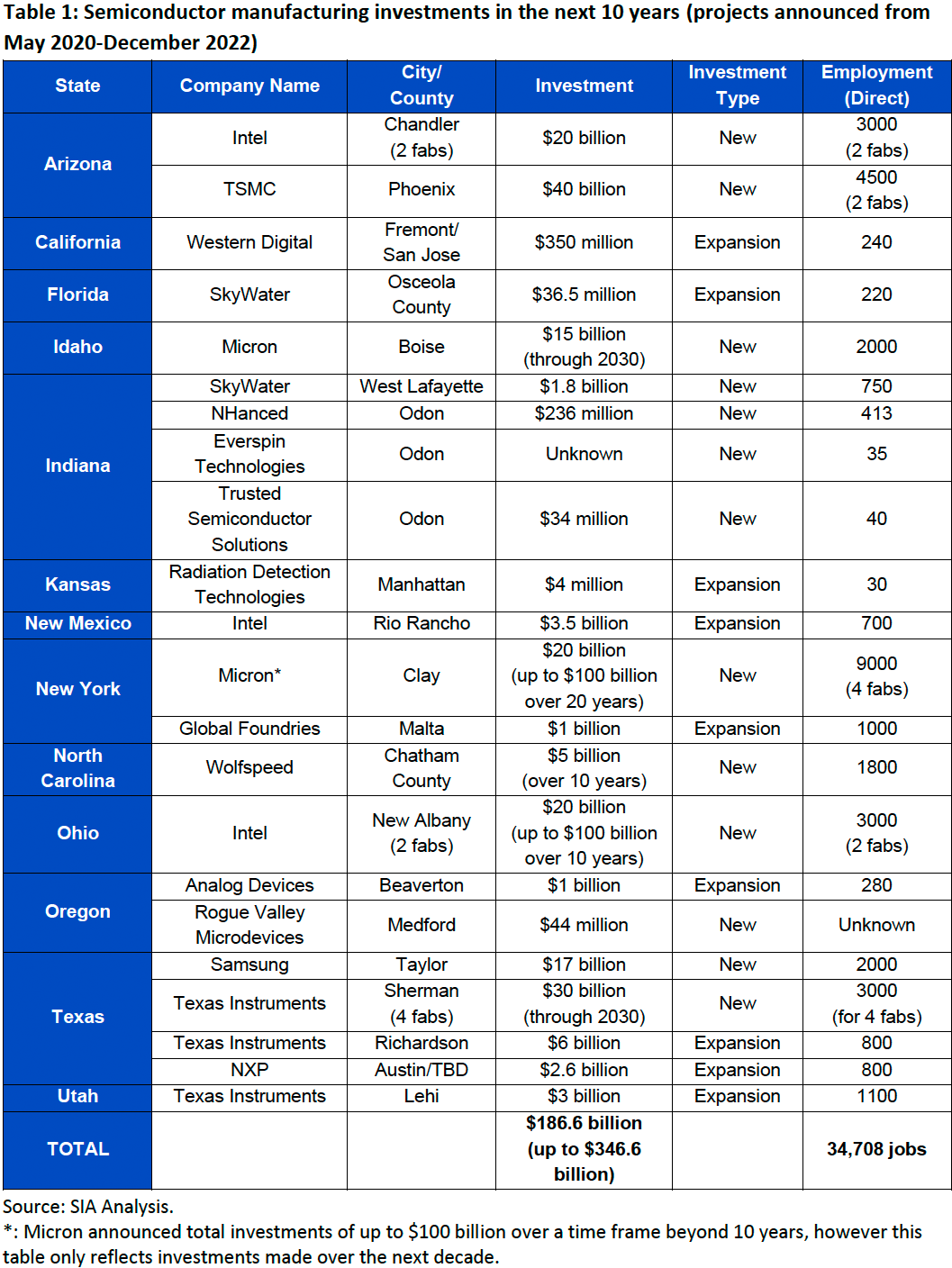

The CHIPS act was first introduced in the Spring of 2020 and aroused immediate attention among the semiconductor industry's leaders. TSMC was first to announce a major new fab project in Arizona in mid-May 2020 and since then over 40 new semiconductor ecosystem projects were announced all across the U.S. Eventually, these fabs and other production facilities will enable some 40,000 direct well-paid jobs.

When it comes to actual semiconductor fabrication plants, 13 new fabs are being built in the U.S. and nine are expanding, not only reviving American semiconductor industry but also impacting the production of electronics in the USA. Ten more new fab phases have been announced by various makers like Intel, TSMC and Texas Instruments.

The new fabs will produce everything from simple power management ICs (PMICs) and audio amplifiers to innovative memory to advanced CPUs, GPUs and SoCs for a variety of applications.

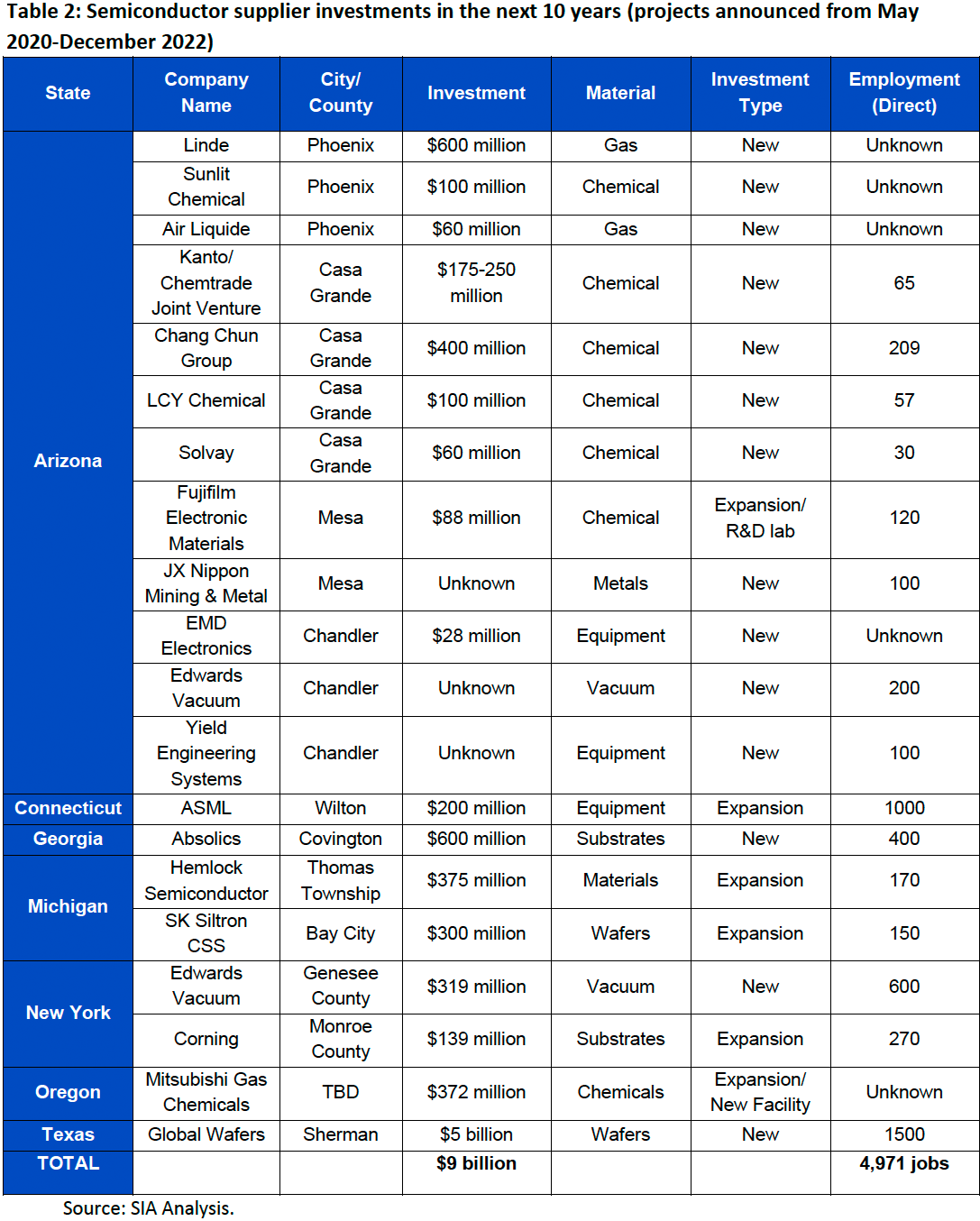

In addition, 20 equipment and materials supplier projects that will source gas, chemicals, tools, and wafers for chip fabs are being built in the USA with 12 of them set to be located in Arizona, where Intel and TSMC are setting up their new production facilities.

Producing chips in the U.S. is important from national security, supply chain reliability and economic points of view. But U.S. made chips will also inspire more electronics production in the country. While we hardly expect companies like Apple, Dell or HPE to transfer manufacturing of their PCs and smartphones to the U.S., some other makers can do just that. Of course, because modern production is heavily automated, production facilities still employ people.

The SIA claims that for each U.S. worker directly employed by the semiconductor industry, an additional 5.7 jobs are created in the wider U.S. economy.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

"SIA looks forward to working with the Commerce Department to ensure the CHIPS Act is implemented in an effective, efficient, and timely manner," a statement by the association reads. "Doing so will help reinvigorate U.S. chip production and innovation and deliver major benefits for America’s economy, job creation, national security, supply chain resilience, and technology leadership."

Anton Shilov is a contributing writer at Tom’s Hardware. Over the past couple of decades, he has covered everything from CPUs and GPUs to supercomputers and from modern process technologies and latest fab tools to high-tech industry trends.

-

JTWrenn ReplyDavidMV said:Labor in Mexico is about the same price as China now. Mexico has a long history of electronics assembly. Why don't we make the chips in the US and do the packaging and assembly in Mexico for the North American market?

Quality control would be the big issue. I think we should be working on a work transition pipeline for coal workers to start making chips. Grunt work but much cleaner and less dangerous. If we could make the pay similar it would be a good way to push a more holistic transition away from coal. -

DavidLejdar Quite ambitious, considering that the U.S. was already struggling to keep up a supply of infant formula by itself, huh? The shortage of which was made worse by there having been import restrictions, after the easing of which imports from Europe helped some.Reply

DavidMV said:Labor in Mexico is about the same price as China now. Mexico has a long history of electronics assembly. Why don't we make the chips in the US and do the packaging and assembly in Mexico for the North American market? There is no good reason the parts that make up my cellphone need to cross the ocean multiple times. I'm sure something similar could be done in Europe. Make the chips in Germany and do the assembly in eastern Europe. Keep things more local when possible. Both markets are plenty big to support it.

Not really that big a market globally though. E.g. a few years ago, NA and Europe had around 200 million smartphones shipped each per year. Worldwide the total number was nearly 1,500 million.

Also, Apple smartphones have a market share of 57.58% in the U.S. So, with a total yearly smartphone revenue of around $80bn in the U.S., that's less that $40bn to be had on the smartphone market, out of nearly $450bn globally.

Which isn't to say that it wouldn't make sense for a bit more localized production, nor does it mean that every of the mentioned companies is in it for the smartphones (only), with there also e.g. the internet of things. And having to rely on the goodwill of Xi, sure not necessarily great.

But Washington's idea that an electronics company should as if a commune garden sell stuff only locally, the income won't necessarily be that big to pay for modernisation of that garden every few years (something which in certain technological branches is quite needed), and therefore not necessarily have much to export when their product ends up generations behind and not necessarily cheaper than someone producing 10x as many items every day, with their suppliers also churning out a lot more and therefore being able to afford lower margin per item (even if initial material costs are all the same everywhere), and so on. -

umeng2002_2 It's bad to have all of your high tech products assembled a few miles from your enemy or in your enemy's country. There are no problems with Taiwan other than it's so close to China and China wants to invade it. It's almost as bad as having all of you antibiotics manufactured by Ch...Reply

I hope this isn't just for new nodes. The entire car industry was crippled from the lock downs due to chip production issues... not some like making tires or engines. This has way more impact than just laptops and phones. -

bit_user It's a good move, but it's going to require some follow-up investment. It can't be a one-and-done infusion, or the new fabs will eventually close and not get replaced.Reply

Also, we really need funding of academic research to go along with it, if we're to truly achieve and maintain leadership in silicon fabrication and similar fields. Does anyone know if the CHIPS act includes anything of the sort? -

bit_user Reply

Foxconn had plants in Mexico, a long time ago. I presume they're still around. There are North/South rail corridors that support some of this trade. And there's NAFTA, which I think makes it fairly frictionless.DavidMV said:Labor in Mexico is about the same price as China now. Mexico has a long history of electronics assembly. Why don't we make the chips in the US and do the packaging and assembly in Mexico for the North American market? -

bit_user Reply

Hmmm... none of the new plants seem to be located in West Virginia. One is in Idaho, which I think is another big coal state.JTWrenn said:I think we should be working on a work transition pipeline for coal workers to start making chips.

I'm not sure it's such an easy transition to make, but I support the idea of providing retraining for whatever field someone wants to go into. When we're talking about losing entrenched industries, you have to think not only about existing workers, but also what has the potential to keep their kids from moving away and ideally even drawing in new workers. If the local economy sees growth, it could create other job opportunities for ex-coal workers, such as in construction.

That's not due to lack of manufacturing capacity. That's because a major production facility got halted for inspections due to contamination concerns, after some infants died. Apparently, there wasn't nearly enough slack among the competing producers, which is why the shortage happened. The worst shortages were in specialized formulas, and maybe there was little or no competition in some of those niches?DavidLejdar said:Quite ambitious, considering that the U.S. was already struggling to keep up a supply of infant formula by itself, huh?

But, probably the USA/Europe handsets were higher-end & higher-margin than most of the rest. The majority of the world's cell phones only cost around $100 and probably have very thin margins.DavidLejdar said:Not really that big a market globally though. E.g. a few years ago, NA and Europe had around 200 million smartphones shipped each per year. Worldwide the total number was nearly 1,500 million.