System Builder Marathon, December 2010: $500 PC

Overclocking

When the time came to tinker outside of spec, our first order of business was to determine if the dormant processing core could be successfully unlocked. We had a stable fourth core in September, but this time our system refused to even boot as an Athlon II X4. The motherboard’s design, unfortunately, made resetting the system a bit tedious, as accessing the clear CMOS jumper requires removal of the graphics card.

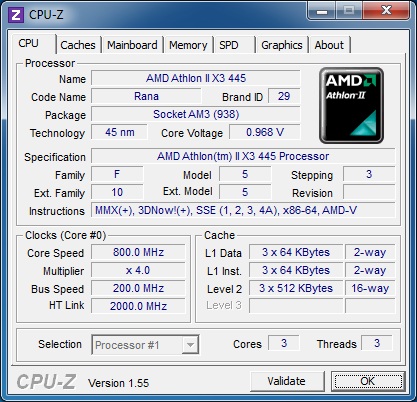

While unlocking was a failure, our Athlon II had a good deal of headroom for increasing core speed. The chip’s VID (Voltage ID) was 1.3 V, as opposed to the September machine's 1.4 V. Once again, the motherboard overvolted a bit beyond that. At stock voltage, stability was found beyond 3.4 GHz.

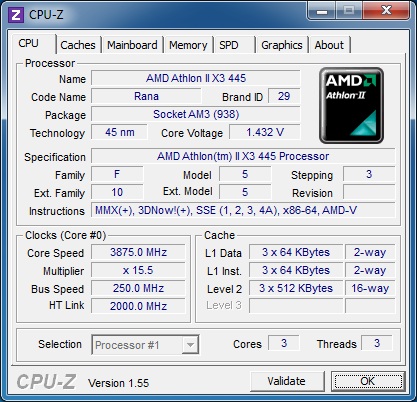

We only took the CPU up to 1.4 V in the BIOS, which CPU-Z reported as 1.432 V at idle and 1.464 V during load, finally settling for a respectable 3.875 GHz (250 * 15.5). This Mushkin RAM was found to have little headroom, so the 250 MHz reference clock worked out for keeping our RAM within spec (at DDR3-1333). Maximum available CPU-NB frequency was 2500 MHz, but we settled for 2250 MHz due to the motherboard's cooling and lack of adjustable CPU-NB voltage.

The Sparkle GeForce GTX 460 also had a decent amount of headroom for increased frequencies, and the quiet cooler was effective for overclocking without overriding the auto fan settings. Starting at a reference 675 MHz core and 1350 MHz shaders, our card topped out at 835/1670 MHz, respectively. We didn’t push the GDDR5 memory all the way to its breaking point, calling it quits after raising it from 900 MHz (3600 MT/s effective) up to 1060 MHz (4240 MT/s). These frequencies were then dialed back to 823/1640/1050 (4200) during our overclocked set of benchmarks.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

-

LuckyDucky7 And this is really the only PC build that will stay relevant come January- it will remain the only budget platform that can be overclocked, after all.Reply

Incidentally, this would be the only PC you'd want to contemplate building right now (since the new Core i3s don't come out immediately like the i5s and i7s do- and the Pentium G8XX series doesn't allow overclocking of its platform.) -

yyk71200 I wouldn't be very comfortable using a 380 watt PSU for a long time for GTX 460 even if it is good quality. Perhaps, I would put in something of 450 watt or higher.Reply -

Crashman LuckyDucky7And this is really the only PC build that will stay relevant come January- it will remain the only budget platform that can be overclocked, after all.Incidentally, this would be the only PC you'd want to contemplate building right now (since the new Core i3s don't come out immediately like the i5s and i7s do- and the Pentium G8XX series doesn't allow overclocking of its platform.)So you think there's going to be a replacement platform for the $2000 PC in January? That's not going to happen for a while. Or are you suggesting the next $2000 PC should be downgraded to P67?Reply -

dragoon190 I haven't been keeping up with the system marathon much, but what's the reasoning for choosing nVidia card over AMD's? Just wondering since I'm thinking about upgrading my computer soon.Reply -

jj463rd A really nice build this time.However the price of the case and power supply has gone up in price over at newegg.I haven't checked the prices of the other components though.This build seems to perform quite well especially in the gaming benchmarks.Good job!Reply -

tstng I would've gone with a 6850 instead of the 460. It's a tad cheaper, not at all slower if you don't start cranckin' up the tesselation, and should fit the 380W psu a lot better. But a solid build by all means.Reply