Radeon HD 6990M And GeForce GTX 580M: A Beautiful Lie

We’ve been more than outspoken about the naming AMD and Nvidia use for their mobile GPUs. Are they really trying to mislead buyers, though? We briefly examine their methodology and frame that against the limitations of high-end mobile computing.

Mobile Model Shenanigans: What's In A Name?

Power consumption is the big neutralizer when it comes to separating desktop and mobile component design. As you know, power is dissipated as heat, and heat is public enemy number one. We certainly can’t walk around with three-inch-thick notebooks that consist of more copper than component space and require desktop-sized power supplies. Even if such a device were portable, we surely wouldn't want it resting on our...laps.

So, we're not unreasonable here. The idea that certain pieces of hardware have to be downclocked before they're deemed suitable in notebooks is acceptable to us.

But then came the naming games. The earliest any of us can remember a mobile part being upgraded (in spirit, at least) to an inflated model name was when ATI’s Radeon 9600 XT magically turned into the much larger Mobility 9700. ATI could have excused that move with the explanation that the Radeon 9600 XT outperformed an underclocked Radeon 9700 desktop GPU at similar power levels, but that was just the beginning of a long journey down the rabbit hole.

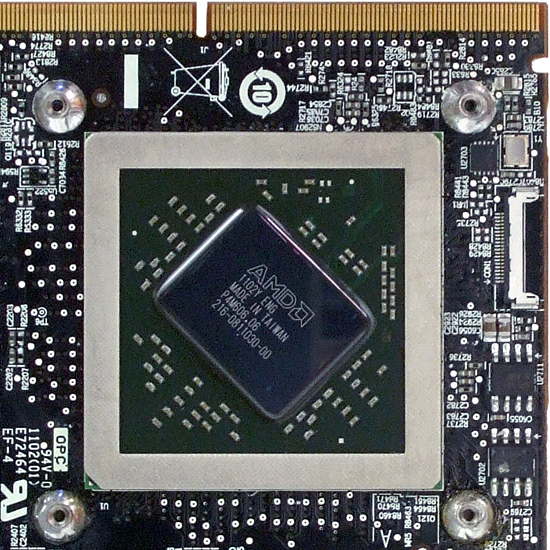

Stranger the naming became, until we finally ended up with underclocked upper-mainstream gaming GPUs getting the names of their extreme counterparts in the Radeon HD 6970M and GeForce GTX 580M. But all of that paled in comparison to one of AMD’s most recent mobile releases, the single-GPU Radeon HD 6990M.

You might expect the 6990M to consist of two Radeon HD 6970M GPUs, since that's how we get a desktop-class Radeon HD 6990.

Instead, we see AMD switch from an underclocked version of its Radeon HD 6850 to an underclocked version of its Radeon HD 6870. Whereas the desktop Radeon HD 6990 has almost two times the raw computational power of the Radeon HD 6970, the 6990M gains less than 25% over AMD's 6970M.

| Desktop vs Mobility Radeon Graphics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Desktop Radeon HD 6990 | Desktop Radeon HD 6970 | Radeon HD 6970M | Radeon HD 6990M |

| Transistors | 5.28 billion | 2.64 billion | 1.7 billion | 1.7 billion |

| Engine Clock | 830 MHz | 880 MHz | 680 MHz | 715 MHz |

| Shader (ALUs) | 3072 | 1536 | 960 | 1120 |

| Texture Units | 192 | 96 | 48 | 48 |

| ROP Units | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Compute Performance | 5.1 TFLOPS | 2.7 TFLOPS | 1.3 TFLOPS | 1.60 TFLOPS |

| DRAM Type | GDDR5-5000 | GDDR5-5500 | GDDR5-3600 | GDDR5-3600 |

| DRAM Interface | 256-bits per GPU | 256-bits | 256-bits | 256-bits |

| Memory Bandwidth | 160 GB/s per GPU | 176 GB/s | 115.2 GB/s | 115.2 GB/s |

| TDP | 375 W | 151 W | 75 W | 100 W |

Both AMD and Nvidia excuse this naming disparity by affixing their flagship desktop model name to their flagship mobile products. However, we see this as a great way to deceive uninitiated notebook buyers. After all, the performance profile of each desktop GPU is trumpeted to the masses before the notebook GPUs with similar names are introduced. So, “common knowledge” works against the partially-informed buyer.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Man, just imagine if Intel called its mobile flagship the Core i7-3960XM. Though, at $1050, the four-core, 2.7 GHz Core i7-2960XM is only one digit away from following along...

Amidst all of this, some say that the other limitations of mobile computing make additional GPU power unnecessary. Notebook screens are relatively small, with moderate resolutions that typically don’t require as much graphics horsepower to drive. Although they exist, we haven't yet tested any mobile gaming platforms capable of spanning across three screens via Eyefinity or Surround, and single-screen resolutions as high as 1920x1080 aren't particularly taxing on today's graphics processors.

Nevertheless, today we’ll we compare the real performance differences between desktop and notebook GPUs while testing within the limits of a real high-end desktop replacement notebook.

Current page: Mobile Model Shenanigans: What's In A Name?

Next Page Test Settings And Benchmarks-

Yargnit The HD 6990M is certainly the worst in a long line of ever-increasing false advertising by GPU manufacturers when it comes to their mobile cards.Reply

Every generation is more guilty than the one before, but AMD indeed hit a new low when they used the name of their dual-GPU flagship to go along with a single-GPU mobile card. (Not even based off the same GPU at that)

I wonder what the chances of someone successfully filing a false advertising suit for this would be? Especially in the EU where they seem much stricter about that stuff than the US is, I'd have to think they'd have a decent shot. (This is at least as bad as the whole LED/LCD TV thing that the courts ruled against the manufacturers on)

I can let some reasonable under-clocking (say 25% at most) get by for mobile GPU's under the same name, but they should have to be based off the same GPU as the desktop card that they are named after at least, and in the case of using the name of a dual-GPU card they should actually have to be dual GPU cards.

Either put an actual 6990 in the laptop, or call it a HD 6870m. -

Inferno1217 This is nothing new to the laptop world and is common knowledge. You can't expect 580 or 6990 desktop performance out of a mobile 580 or 6990 solutions (note the M at the end). This article may help newcomers understand the differences between mobile and desktop gpu's.Reply -

Crashman el33tWhat on earth took you guys so long to realize this??This is something like the third article to point these problems out, but it's the first to use the desktop 6990. Tom's Hardware simply doesn't have enough 6990's for every tester to have his own :)Reply -

alanim Normally I wouldn't really see a problem with this, because as far as I understand the numbers are just there to show a tier on how powerful the graphics cards are, and since this is the 6990M, one would assume that it's the highest tier for the current generation mobile graphics card.Reply

Now on the otherhand they're using the numbers as their desktop counterparts just with a tacked on M for mobile, I assume the only reason they don't use a different number is because it could confuse the buyers into thinking it was either a newer or older generation part, although that's assuming most people who buy these know what the current generation parts are(which I assume is not the case).

What you're seeing isn't actually them trying to deceive people it's actually them using a streamlined approach. All this 6990M means is that it's top tier for mobile GPU's of the current generation, this is the consequence of trying to make the numbers more buyer friendly. Good Idea, Good Usage, but relies heavily on customer knowledge and understanding on what they're buying, but that could be said for almost anything. -

SteelCity1981 in Nvidia and AMD's defense there is an 'M' at the end so it's not false advertising. lolReply -

aznshinobi Agreed, there is an M for a reason. It's the buyers fault for not researching. Most buyers just buy the most expensive product and assume it's good. This will teach them otherwise.Reply -

Crashman aznshinobiAgreed, there is an M for a reason. It's the buyers fault for not researching. Most buyers just buy the most expensive product and assume it's good. This will teach them otherwise.That's why the article was published :)Reply