FCAT VR: GPU And CPU Performance in Virtual Reality

FCAT VR: Meet Our Newest Test Tool

Although the Oculus Rift launched almost one year ago, we still don't have a good way to benchmark graphics performance in VR. Until now. Over the past several months, we worked closely with Nvidia to test a new tool called FCAT VR, which allows us to quantify what you see in your HMD.

Why should you care? Both Oculus and HTC perform a lot of behind-the-scenes magic in their respective runtimes to make virtual reality responsive, and in turn immersive, on a wide range of hardware platforms. While capturing what happens between the runtime and HMD wasn't previously impossible, it was most definitely a cumbersome process. Not only does FCAT VR simplify data collection, it also provides a way for us to visualize complicated concepts in an easy-to-interpret way. We think you'll like it.

But First, A Little History

More than three years ago, we published Challenging FPS: Testing SLI And CrossFire Using Video Capture. In that story, Don Woligroski introduced a new way to benchmark graphics cards based on video capture, along with a suite of overlays and Perl scripts called FCAT (for Frame Capture Analysis Tool).

FCAT was developed by Nvidia as a means of quantifying performance. But why go to all of the trouble of creating a new evaluation methodology when the then-standard, Fraps, already gave us the numbers we needed to calculate average FPS, frame rate over time, and even individual frame rendering times?

If you remember back to 2013, the SLI and CrossFire multi-GPU technologies were under scrutiny. It was argued that the numbers Fraps reported weren’t always representative of on-screen experiences. This phenomenon was attributed to where Fraps operated in the display pipeline. The software counted every frame rendered when, in reality, some frames only appeared partially. Worse, others never made it to the screen at all.

By instead capturing the graphics card’s output to a video file and analyzing the sequence of frames, FCAT was able to represent the same information gamers saw displayed on their monitors. To make a long story short, FCAT helped us illustrate how Fraps’ results sometimes diverged from real performance. Of course, Nvidia's coding efforts weren't intended to be altruistic. The company already had mechanisms in its driver to regulate the rate at which frames were displayed to improve perceived smoothness. AMD did not, so a lot of its frames were shown to be wasted. Not long after, AMD incorporated similar pacing technology to ameliorate the issue.

Unfortunately, working with FCAT was immensely resource-intensive. Once graphics vendors enabled frame pacing in their drivers to mitigate short (runt) and dropped frames, we considered the tool’s main purpose satisfied, and largely moved away from it in favor of testing more games, quality settings, and resolutions in the same amount of time. Today we largely rely on PresentMon (and our own custom front-end) for testing in DirectX 11, DirectX 12, and Vulkan.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Benchmarking VR: A Challenger Appears

Unfortunately, none of the typical testing tools are suitable for benchmarking graphics performance in virtual reality through HTC’s Vive or Oculus’ Rift; they can measure frames that the game engine generates, but they miss all of what happens afterwards in the VR runtime before those frames appear in the HMD. VRMark and VRScore get us part of the way there with synthetic measurements, but we're usually more interested in making real-world comparisons.

Enter FCAT VR, which is conceptually similar to the original version. This time, however, there are two ways to benchmark: a hardware-based capture solution or an all-software approach. Both facilitate similar results (albeit presented somewhat differently). But the software tool is naturally more accessible.

Really, the hardware implementation exists as a validation measure—because FCAT comes from Nvidia, readers, reviewers, and other vendors need to have confidence in any test results generated with it. A few media outlets already have their hands on the necessary $2000+ capture card and heavy-duty storage subsystem required to test via video-based analysis. But expect most editors to benchmark through software, should it prove trustworthy by the community at large.

What exactly are we looking for here? Nvidia does a pretty stellar job describing the VR pipeline and where things can go wrong, so we’ll borrow from the company’s documentation, editing for brevity.

“Today’s leading high-end VR headsets, the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, both refresh their screen at a fixed interval, 90 Hz, which equates to one frame every ~11.1ms. V-sync is enabled to prevent tearing, which can cause major discomfort to the user.

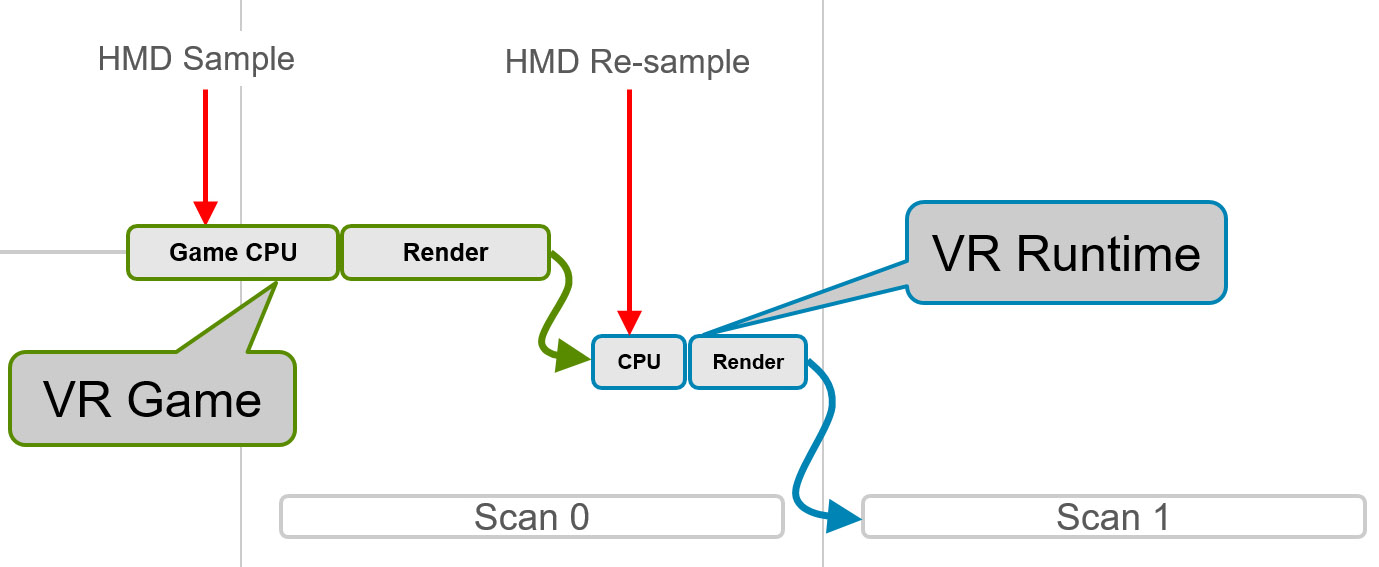

The mechanism for delivering frames can be divided into two parts: the VR game and the VR runtime. When timing requirements are satisfied and the process works correctly, the following sequence is observed:

- The VR game samples the current headset position sensor and updates the camera position to correctly track a user’s head position.

- The game then establishes a graphics frame, and the GPU renders the new frame to a texture (not the final display).

- The VR runtime reads the new texture, modifies it, and generates a final image that is displayed on the headset display. Two interesting modifications include color correction and lens correction, but the work done by the VR runtime can be much more elaborate.

The following figure shows what this looks like in a timing chart.

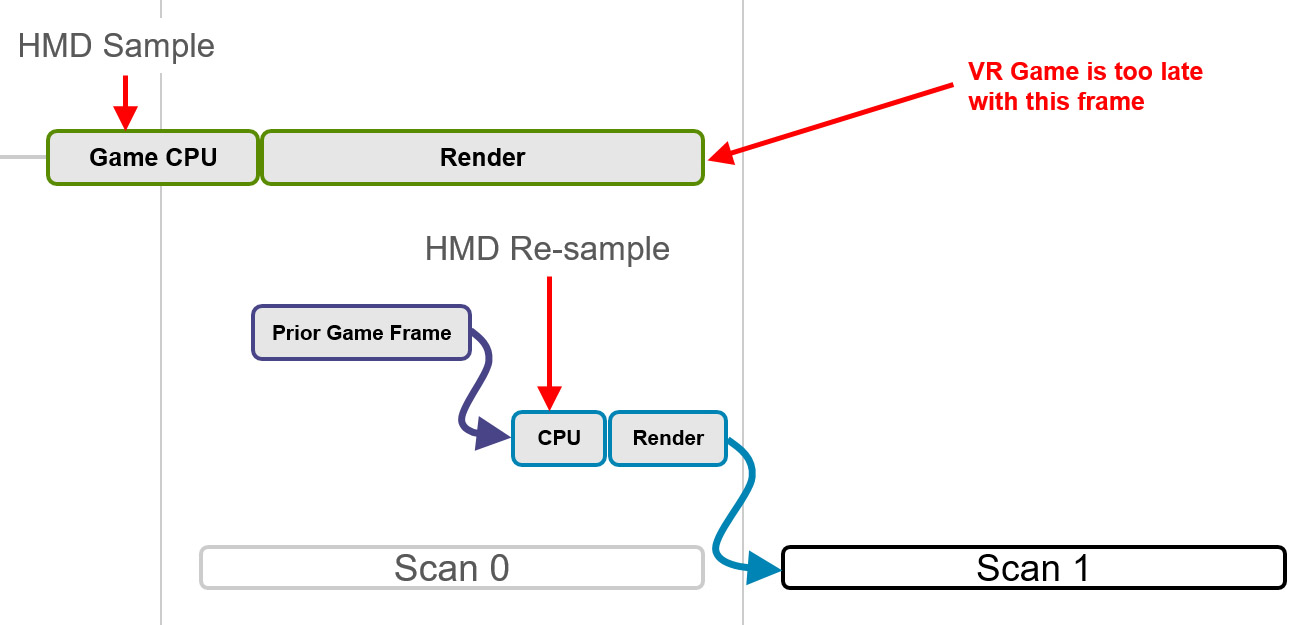

The job of the runtime becomes significantly more complex if the time to generate a frame exceeds the refresh interval. In that case, the total elapsed time for the combined VR game and VR runtime is too long, and the frame will not be ready to display at the beginning of the next scan.

In this case, the HMD would typically redisplay the prior rendered frame from the runtime, but for VR that experience is unacceptable because repeating an old frame on a headset display ignores head motion and results in a poor user experience.

Runtimes use a variety of techniques to improve this, including algorithms that synthesize a new frame rather than repeat the old one. Most of the techniques center on the idea of re-projection, which uses the most recent head sensor location input to adjust the old frame to match the current head position. This does not improve the animation embedded in a frame—which will suffer from a lower frame rate and judder—but the fluid experience of head motion is improved.

FCAT VR captures four key performance metrics for Rift and Vive:

- Dropped frames (app miss/app drop)

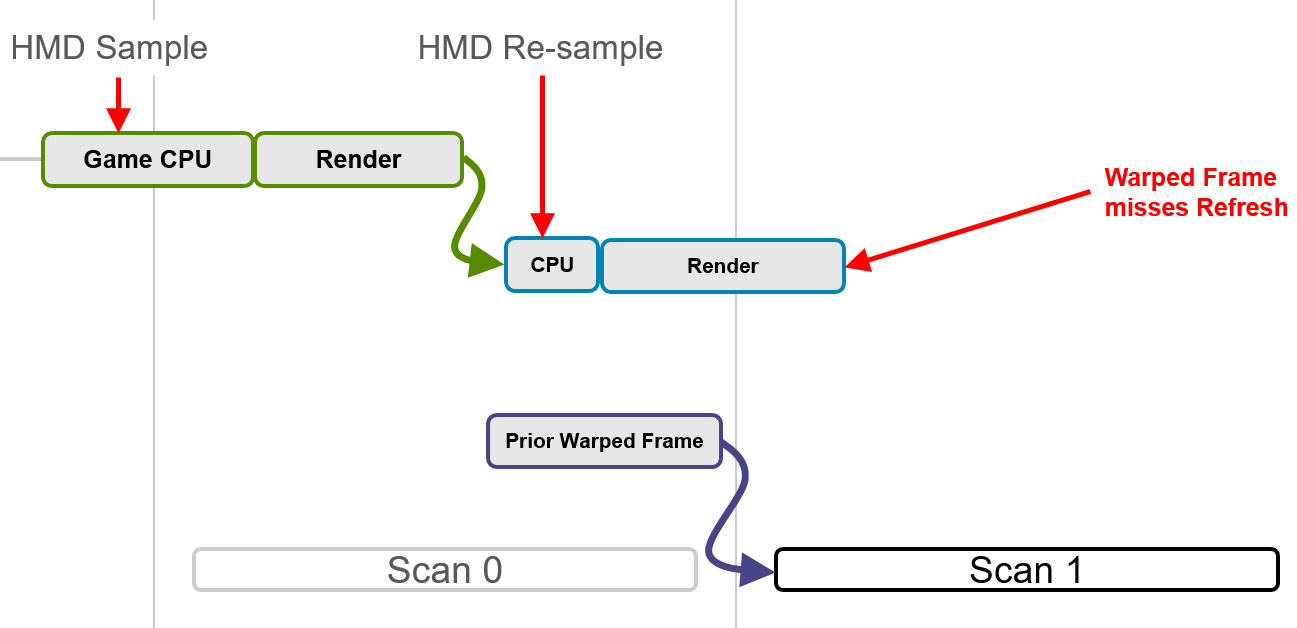

- Warp misses

- In the software version of FCAT, frame time data

- Frames synthesized by asynchronous spacewarp

Whenever the frame rendered by the VR game arrives too late to be displayed in the current refresh interval, a frame drop occurs and causes the game to stutter. Understanding these drops and measuring them provides insight into VR performance.

Warp misses are a more significant issue for the VR experience. A warp miss occurs whenever the runtime fails to produce a new frame (or a re-projected frame) in the current refresh interval. In the preceding figure, a prior warped frame is reshown by the GPU. The user experiences this frozen time as a significant stutter.”

Because we have access to the hardware and software versions of FCAT VR, we’ll introduce them both and compare their results. Then, providing Nvidia’s software tool proves as comparable to the hardware as it claims, we’ll start pitting graphics cards against each other using Nvidia’s utility as our primary source for generating benchmark numbers.

MORE: Best Graphics Cards

Current page: FCAT VR: Meet Our Newest Test Tool

Next Page Hardware And Software: Two Ways To Test-

AndrewJacksonZA A really nice article and a great introduction to FCAT VR. Thanks Chris!Reply

Obvious request that probably everyone will ask of you: please include Ryzen in your tests once you have a sane moment after the hectic launch period. :-)

Now that that's out the way, I can get to my actual question: I would like to know if "Game A" is available on both the Rift and the Vive, would FCAT VR be able to tell you what, if anything, the performance difference is given the same computer hardware please?

Please can you also include multi-GPU setups. They can definitely help, depending on the title, e.g.

https://www.hardocp.com/article/2016/11/30/serious_sam_vr_mgpu_nvidia_gtx_pascal_follow_up/5

https://www.hardocp.com/article/2016/10/24/serious_sam_vr_mgpu_amd_rx_480_follow_up/

I found this statement to be very interesting: "it’s possible to illustrate that 11ms isn’t an absolute threshold for rendering new frames at 90 Hz."

Thank you

Andrew -

cangelini Hi guys,Reply

Ryzen wasn't in my lab yet when this was written, but I do have plans there ;)

Andrew, yes, FCAT VR should allow us to test the same title on two different HMDs and compare their performance.

Multi-GPU is a plan as well, particularly once games begin incorporating better support for it (right now, that's a bit of a problem). -

playingwithplato Do FCAT VR's measurement algorithms tend to favor NVDIA chipsets? Curious, wonder if AMD will release a similar testing tool to measure buffer store/retrieval and render speed <11ms? Would like to see that applied to en environment with their GPUs.Reply -

ffrgtm Fantastic article! I would love to see results with a secondary GPU (non-SLi) dedicated to physics and compare that to the cpu swap tests in AZ Sunshine you've just shown us.Reply -

ffrgtm Reply

A quote from another article on FCAT:19429997 said:Do FCAT VR's measurement algorithms tend to favor NVDIA chipsets? Curious, wonder if AMD will release a similar testing tool to measure buffer store/retrieval and render speed <11ms? Would like to see that applied to en environment with their GPUs.

"While the FCAT VR tool is developed by Nvidia, the company insists it is headset and GPU agnostic, and meant only to capture data. The tool itself doesn’t contain a benchmark; according to the company, the tool logs information directly from the VR runtime."

I'm inclined to believe Nvidia's claim of brand blindness right now... but if AMD ever manages to put forth some real competition then I don't think we could be blamed for becoming more skeptical. It's hard to forget just how far Nvidia and AMD have gone to skew results in the past. -

AndrewJacksonZA Reply

Thank you.19429089 said:Andrew, yes, FCAT VR should allow us to test the same title on two different HMDs and compare their performance.

Multi-GPU is a plan as well, particularly once games begin incorporating better support for it (right now, that's a bit of a problem).

One thing that I might've missed in the article: Has Nvidia open-sourced FCAT and FCAT VR so that everyone can see the code, check it for unbiasedness (is that even a word? :-) and help contribute to the program to make it even better? -

cangelini Yup, check it out: http://www.geforce.com/whats-new/guides/fcat-vr-download-and-how-to-guideReply

There's a download link in there. I'd be curious to hear from any TH readers who want to mess with it as well! -

thinkspeak Any chance of doing this again but with stock and OC on the maxwell, pascal and AMD cards? The 980 ti really opens up and they generally overclock well, in some cases exceeding the 1070 which would be useful for those debating an upgrading for VRReply