System Builder Marathon Q4 2014: $1600 Performance PC

Power, Heat, Efficiency And Value

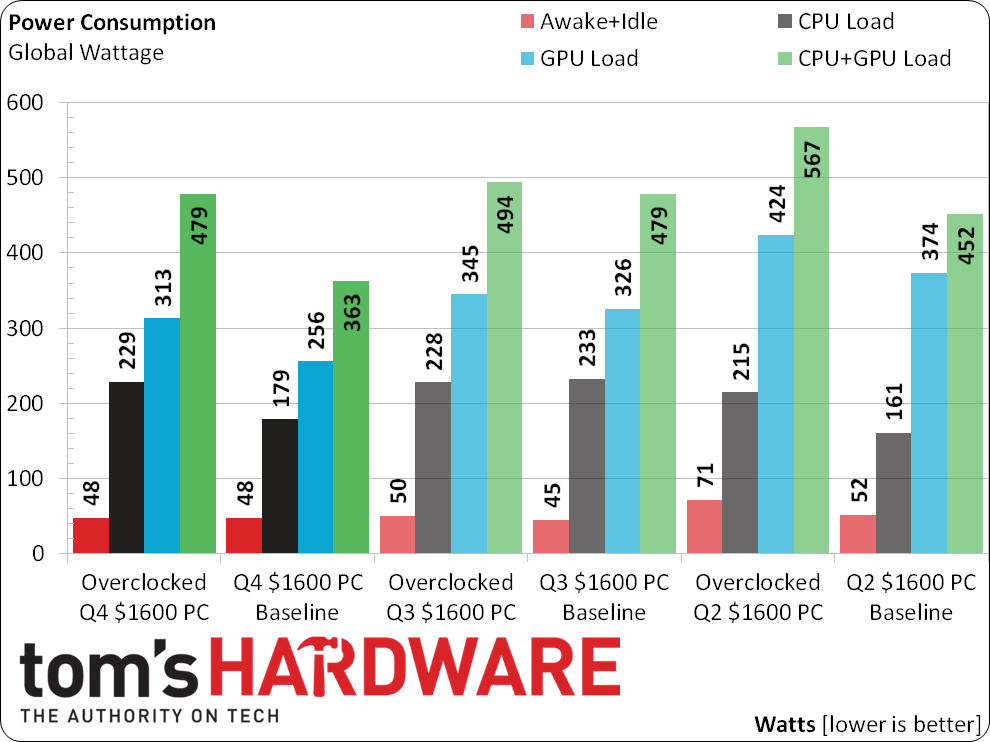

The Q4 machine’s GTX 980 graphics card saves an incredible amount of energy compare to Q3’s R9 290X at stock settings, and retains some of that miserliness when overclocked. Though the lower-energy card does ramp up energy use to a much greater extent when overclocked, it also overclocks by a much wider margin.

Even at $90, I might have overspent for the unneeded excess current capability of this quarter’s 750W unit. Then again, I started my search at 650W and didn’t find any better deals at this quality level. Experienced overclocks and servicers alike will tell you stories about the importance of PSU quality and the horrors of PSU failure.

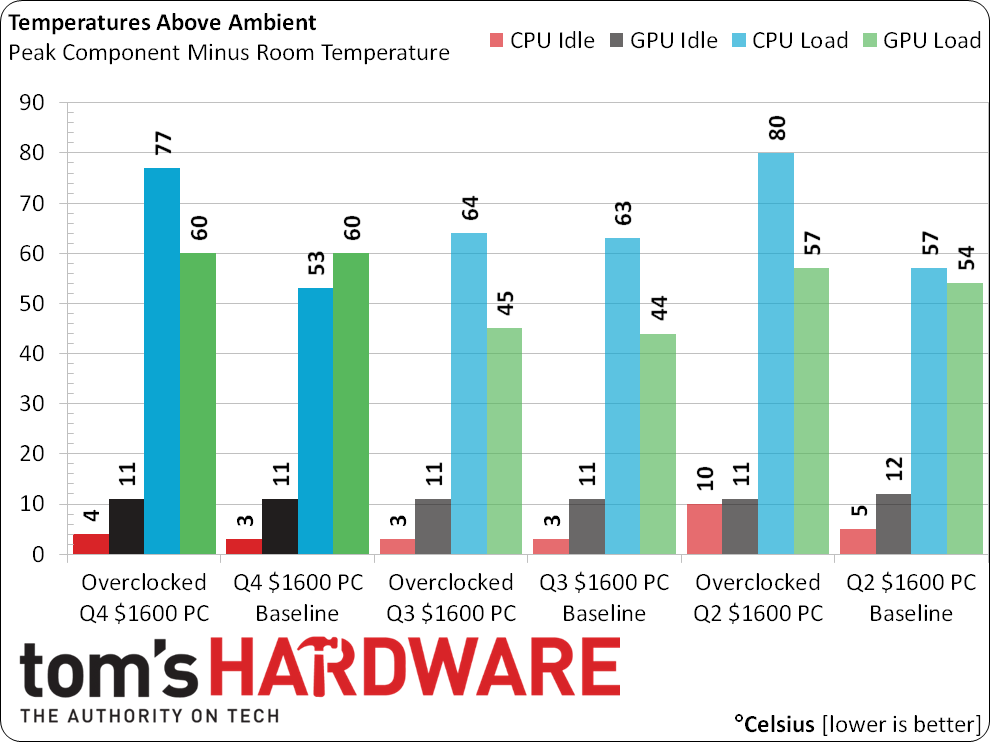

The Q4 machine runs hot. I pulled the side panel from the case and unloaded the GPU, but the CPU still ran hot. Evidence that this isn’t entirely a case issue can be seen in the consistent thermal readings of the GPU at both stock and overclocked settings, though side-panel removal did cool the CPU by a 3-6 degrees. The rear fan doesn’t have enough airflow to function perfectly as an intake for the CPU cooler, but it was probably good enough.

Thermal testing also gave me an opportunity to measure noise level, which hasn’t been charted in prior SBMs. The stock machine idled at 28 dBA (decibels, A-weighting) and climbed to 33 dBA under full load. The overclocked configuration idled at 32 dBA and climbed to 42 dBA under full load. Given this acoustic excellence, why would anyone choose an internally-vented card to “reduce noise”?

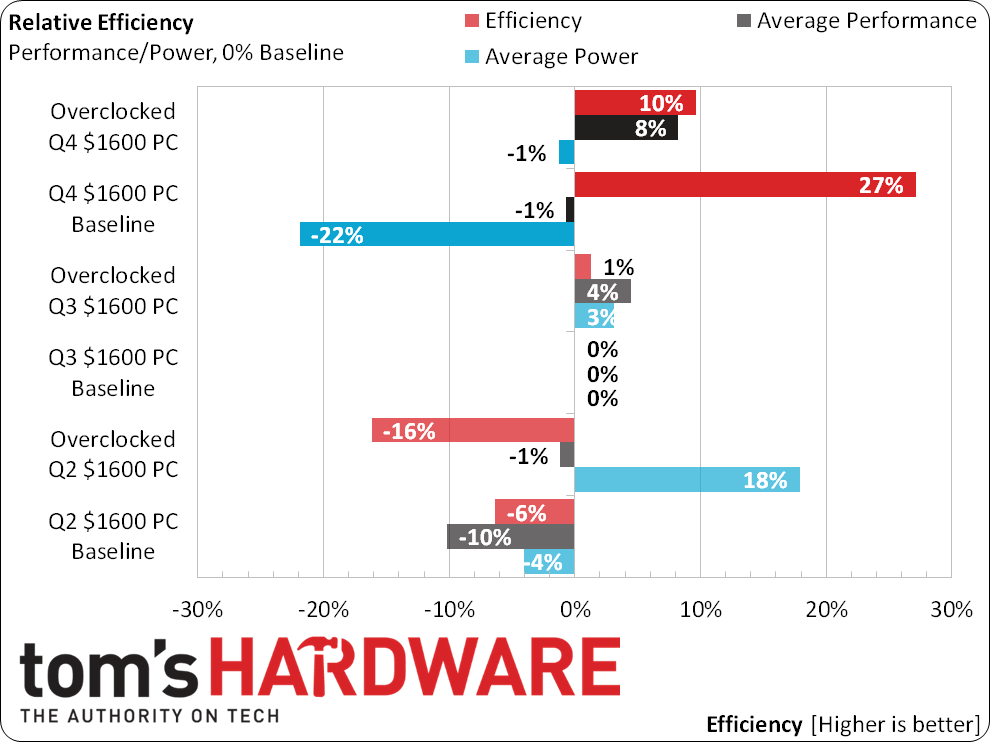

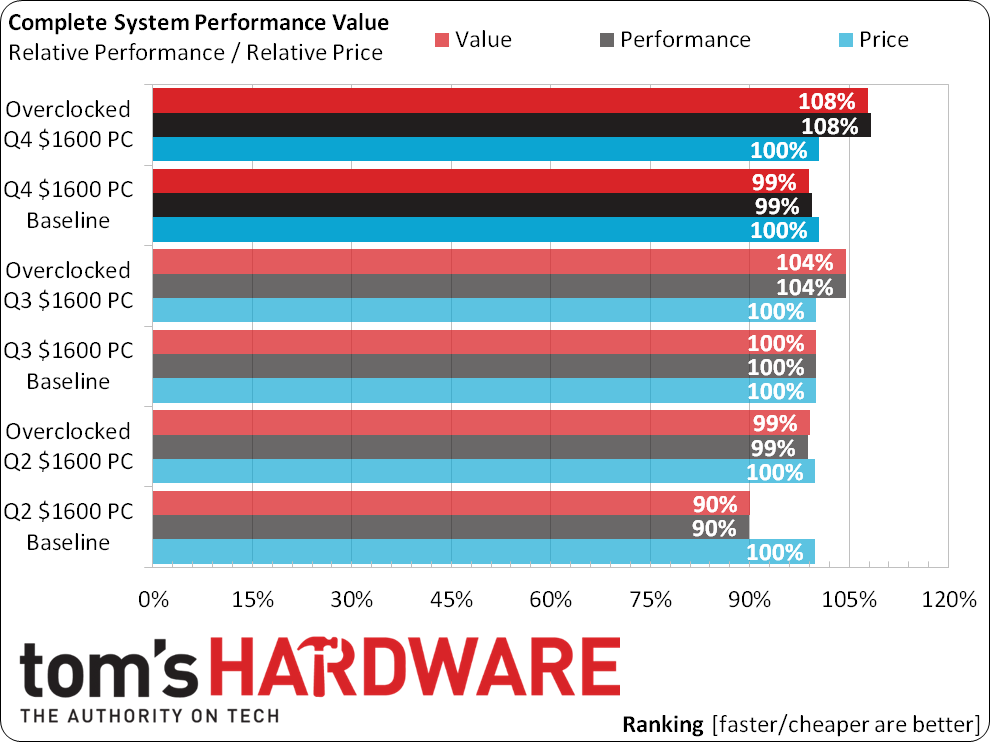

Efficiency compares performance to energy consumed, and this is where the new machine stands. The Q3 baseline system sets the performance baseline, where the performance gained or lost by other machines is compared on a percent basis.

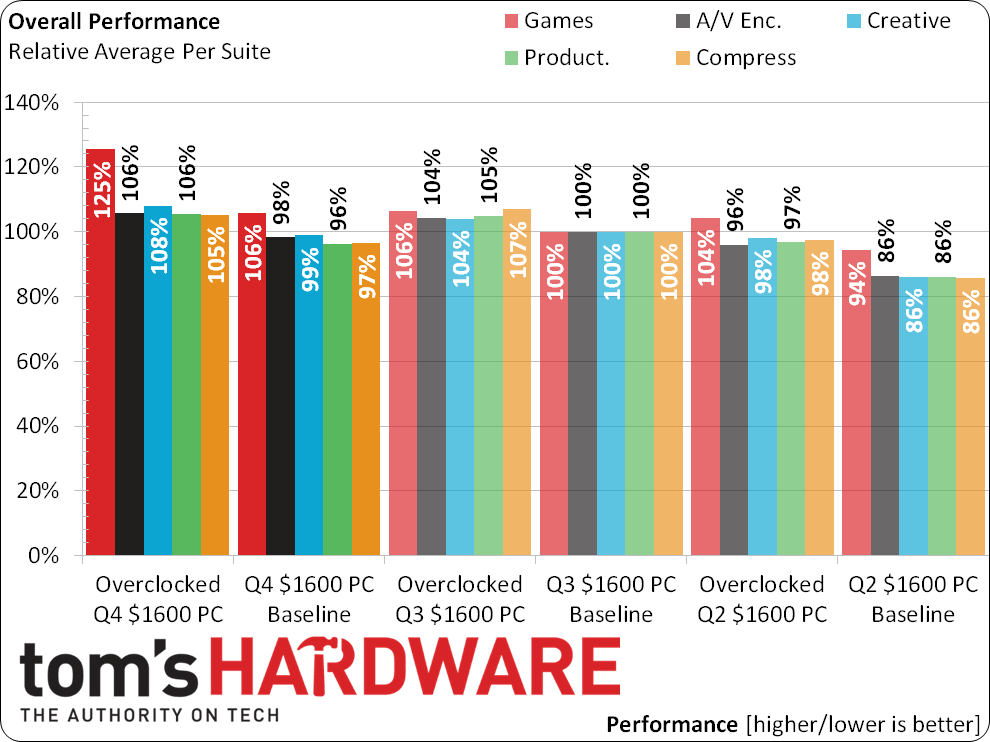

The new machine games better, but both systems needed to be overclocked to make this a fair fight since the previous build used “Enhanced” turbo ratios (a form of overclocking) by default.

Zeroing-out the baseline-machine allows us to compare only the percent above or below baseline, where the term “Relative” refers to how each machine’s score is based on the baseline machine. The overclocked Q4 build for example provide 8% better performance, consumes 1% less energy, and is 10% more efficient than the non-overclocked Q3 system.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

The Q4 baseline shines with a 27% efficiency gain over the Q3 baseline. That green advantage rests almost entirely with the GeForce GTX 980 graphics upgrade, and by green I mean the stuff you use to pay your electric bill.

Had this machine cost $40 less, it would have produced a 1% value lead over the previous build. And that 1% represents the price difference between the card I originally ordered and the identical card that replaced it. I don’t blame the card maker or the seller for following buyer trends, I blame irresponsible reviewers for fostering them. Then again, as a case reviewer, my biases concerning the dumping of heat into a case may skewed in the opposite direction of those who test internal components outside of a case.

But I’m burying the lede again. The overclocked Q4 system wins.

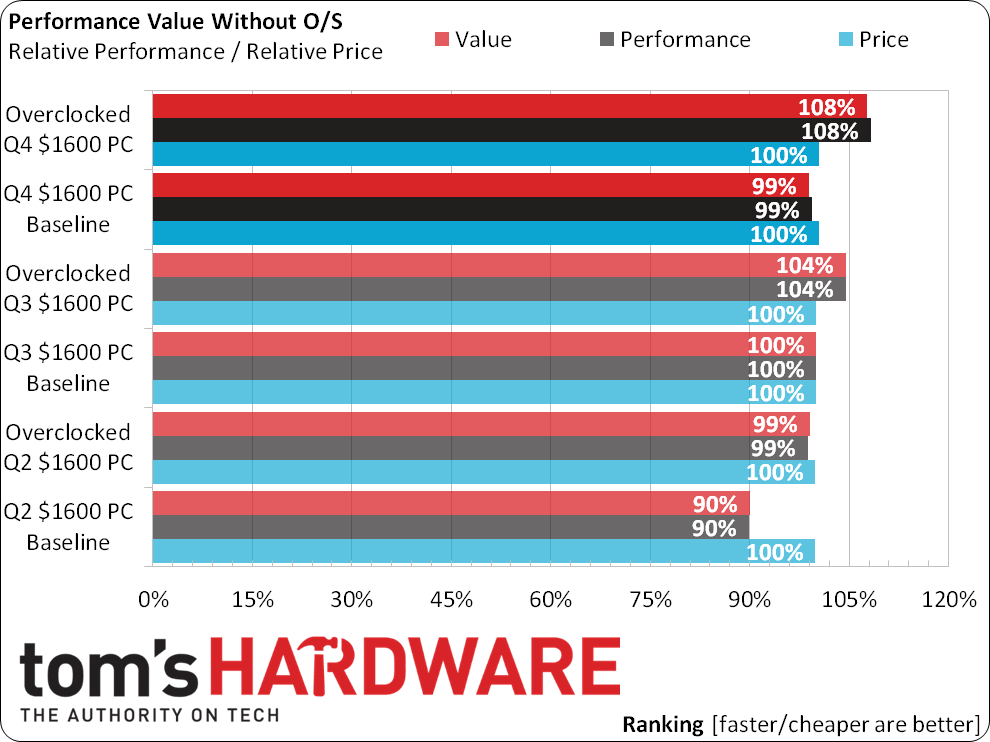

Taking away the OS doesn’t change these numbers by much, because the systems have so much else in common. I again could have claimed a victory for both baseline and O/C results had my intended card shipped, but am left with only an O/C victory instead.

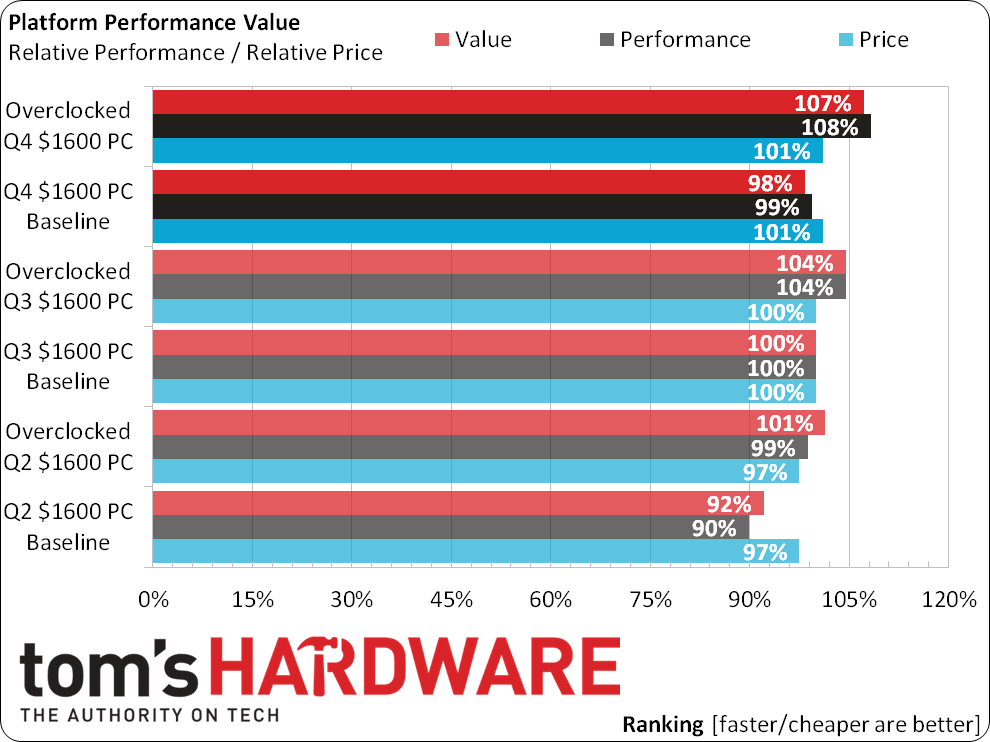

The numbers spread out a little more when I reduce the system to only the parts needed to perform benchmarks, but the new O/C configuration maintains its lead.

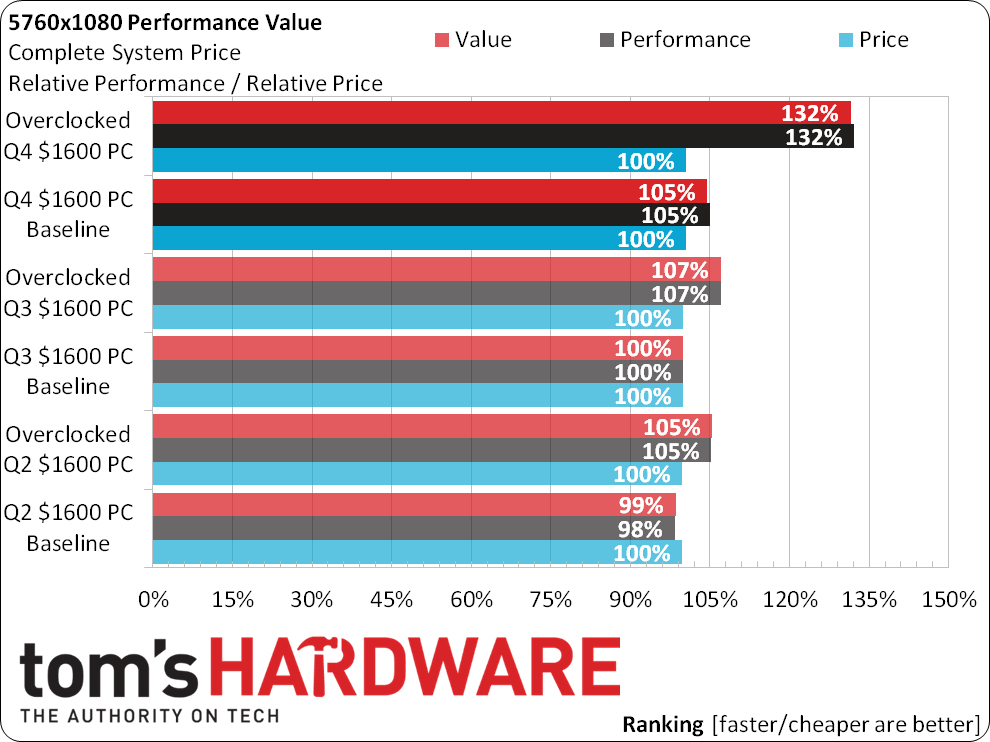

Gaming is the big advantage of new graphics technology, and we see that its greatest overall effect came at ultra-high resolution. A lead that big required a big overclock, and I’m happy the GTX 980 obliged.

And now to answer my original qustion: A part that adds 2% to a machine's cost but at least 4% to its performance while simultaneously increasing efficiency, Nvidia's Maxwell-based GTX 980 is indeed the smarter choice for $1600 performance machines.

-

cmi86 With $60 for a case you could have done so much better than that atrocious smurf turd. If you want me to spend $1,600 on a PC it better look the part as much as it plays the part. NZXT source 210, Antec GX-500, Bitfenix Neo-100, Rosewill Redbone, Thermaltake CA1B2/Commander/Versa and the list goes on and on and on... and on.Reply

BTW, These were only $50 cases netting you $10 on your budget. -

Onus Never mind the atrocious color, how was the case otherwise? Sturdy? Any sharp edges? Front panel cable lengths? Cable management space?Reply

You addressed my thoughts on the oversized PSU; if 650W of similar quality were not cheaper, I might have done the same thing.

I can't help but wonder how SLI of two lesser cards would have performed. Won't two GTX760s beat a GTX980? -

elbert I would have tried to wiggle around 2x 970's for about $660ish. Saved money on the heatsink with a CM 212 evo and a bit cheaper ssd.Reply -

Onus It might have been hard to squeeze out that $60 without raising eyebrows, but perhaps that might have been done. Use the same cooler Don used though;'no reason to waste money on the Hyper EVO. It is almost certainly a better cooler, but not worth the price difference compared to Don's or one of the other 120mm competitors (including the older Hyper212+).Reply -

UltimateDeep Disappointing, your could cut cost a bit more on the cooler or the case and go for a 128GB SSD and go for GTX 970s in SLI. You could get a LOT more with 970s in SLI.Reply -

jasonelmore Honestly, the whole reason to get a 4790K is because it runs 4.4Ghz Stock. With no overclock. 99% of motherboards will automatically overclock all 4 cores to 4.4ghz using Multi-core enhancement setting.Reply

Why void your warranty for 200mhz OC? not needed for such small gains. 4.4 is fast enough even for 4k gaming -

Vorador2 Spending almost 1000$ on the graphics card and CPU and pairing them up with just freaking 8 Gb of RAM is an insult. I know is the price to fit both on a 1600$ budget, but still...it feels completely unbalanced.Reply -

Crashman Reply

It's a fairly mid-grade case with rolled edges and so forth, and reasonable room for cables. Thermaltake's window is a little hard and thin, which is mostly a shipping issue, and I was a little disappointed that it was too narrow to hold this RAM/Cooler combo in its intended orientation. It would make a very NICE $60 to $70 case, but there are many better options at $80+ (its original price).14919563 said:Never mind the atrocious color, how was the case otherwise? Sturdy? Any sharp edges? Front panel cable lengths? Cable management space?

But it wouldn't have been $60. Remember, I ordered a $560 card and ended up with a $600 card. So going back to the planning stage, 2x 970's would have been $100 more.14920018 said:

It might have been hard to squeeze out that $60 without raising eyebrows14919897 said:I would have tried to wiggle around 2x 970's for about $660ish. Saved money on the heatsink with a CM 212 evo and a bit cheaper ssd.

Intel isn't tracking whether-or-not you overclock...but the reason to pick a 4790k over a 4770k is that, in my experience, Intel is tossing a lot of heat-problem cores into the 4770K parts bin.14920879 said:Honestly, the whole reason to get a 4790K is because it runs 4.4Ghz Stock. With no overclock. 99% of motherboards will automatically overclock all 4 cores to 4.4ghz using Multi-core enhancement setting. Why void your warranty for 200mhz OC? not needed for such small gains. 4.4 is fast enough even for 4k gaming