LAN 102: Network Hardware And Assembly

Wireless Network Logical Topologies

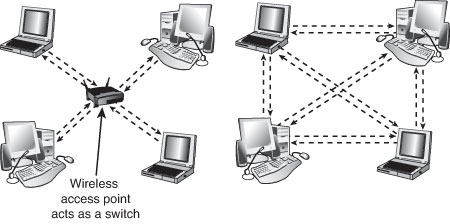

Wireless networks have different topologies, just as wired networks do. However, wireless networks use only two logical topologies:

- Star—The star topology, used by Wi-Fi/IEEE 802.11–based products in the infrastructure mode, resembles the topology used by 10BASE-T and faster versions of Ethernet that use a switch (or hub). The access point takes the place of the switch because stations connect via the access point, rather than directly with each other. This method is much more expensive per unit but permits performance in excess of 10BASE-T Ethernet speeds and has the added bonus of being easier to manage.

- Point-to-point—Bluetooth products (as well as Wi-Fi products in the ad hoc mode) use the point-to-point topology. These devices connect directly with each other and require no access point or other hub-like device to communicate with each other, although shared Internet access does require that all computers connect to a common wireless gateway. The point-to-point topology is much less expensive per unit than a star topology. It is, however, best suited for temporary data sharing with another device (Bluetooth) and is currently much slower than 100BASE-TX networks.

The figure below shows a comparison of wireless networks using these two topologies.

Wireless Network Security

When I was writing the original edition of Upgrading and Repairing PCs back in the 1980s, the hackers’ favorite way of trying to get into a network without authorization was discovering the telephone number of a modem on the network, dialing in with a computer, and guessing the password, as in the movie War Games. Today, war driving has largely replaced this pastime as a popular hacker sport. War driving is the popular name for driving around neighborhoods with a laptop computer equipped with a wireless network card on the lookout for unsecured networks. They’re all too easy to find, and after someone gets onto your network, all the secrets in your computer can be theirs for the taking.

Because wireless networks can be accessed by anyone within signal range who has a NIC matching the same IEEE standard of that wireless network, wireless NICs and access points provide for encryption options. Most access points (even cheaper SOHO models) also provide the capability to limit connections to the access point by using a list of authorized MAC numbers (each NIC has a unique MAC). It’s designed to limit access to authorized devices only.

Although MAC address filtering can be helpful in stopping bandwidth borrowing by your neighbors, it cannot stop attacks because the MAC address can easily be “spoofed” or faked. Consequently, you need to look at other security features included in wireless networks, such as encryption.

Caution: In the past, it was thought that the SSID feature provided by the IEEE 802.11 standards was also a security feature. That’s not the case. A Wi-Fi network’s SSID is nothing more than a network name for the wireless network, much the same as workgroups and domains have network names that identify them. The broadcasting of the SSID can be turned off (when clients look for networks, they won’t immediately see the SSID), which has been thought to provide a minor security benefit. However, Microsoft has determined that a non-broadcast SSID is actually a greater security risk than a broadcast SSID, especially with Windows XP and Windows Server 2003. For details, see “Non-broadcast Wireless Networks with Microsoft Windows” at http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb726942.aspx. In fact, many freely available (and quite powerful) tools exist that allow snooping individuals to quickly discover your SSID even if it’s not being broadcast, thus allowing them to connect to your unsecured wireless network.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

The only way that the SSID can provide a small measure of security for your wireless network is if you change the default SSID provided by the wireless access point or router vendor. The default SSID typically identifies the manufacturer of the device (and sometimes even its model number). A hacker armed with this information can look up the default password and username for the router or access point as well as the default network address range by downloading the documentation from the vendor’s website. Using this information, the hacker could compromise your network if you do not use other security measures, such as WPA/WPA2 encryption. By using a nonstandard SSID and changing the password used by your router’s web-based configuration program, you make it a little more difficult for hackers to attack your network. Follow up these changes by enabling the strongest form of encryption that your wireless network supports.

All Wi-Fi products support at least 40-bit encryption through the wired equivalent privacy (WEP) specification, but the minimum standard on recent products is 64-bit WEP encryption. Many vendors offer 128-bit or 256-bit encryption on their products. However, the 128-bit and stronger encryption feature is more common among enterprise products than SOHO–oriented products. Unfortunately, the WEP specification at any encryption strength has been shown to be notoriously insecure against determined hacking. Enabling WEP keeps a casual snooper at bay, but someone who wants to get into your wireless network won’t have much trouble breaking WEP. For that reason, all wireless network products introduced after 2003 incorporate a different security standard known as Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA). WPA is derived from the developing IEEE 802.11i security standard. WPA-enabled hardware works with existing WEP-compliant devices, and software upgrades are often available for existing devices to make them WPA capable. The latest 802.11g and 802.11n devices also support WPA2, an updated version of WPA that uses a stronger encryption method. (WPA uses TKIP or AES; WPA2 uses AES.)

Note: Unfortunately, most 802.11b wireless network hardware supports only WEP encryption. The lack of support for more powerful encryption standards is a good reason to retire your 802.11b hardware in favor of 802.11g or 802.11n hardware, all of which support WPA or WPA2 encryption.

Upgrading to WPA or WPA2 may also require updates to your OS. For example, Windows XP Service Pack 2 includes support for WPA encryption. However, to use WPA2 with Windows XP Service Pack 2, you must also download the Wireless Client Update for Windows XP with Service Pack 2, or install Service Pack 3. At the http://support.microsoft.com website, look up Knowledge Base article 917021. You should match the encryption level and encryption type used on both the access points and the NICs for best security. Remember that if some of your network supports WPA but other parts support only WEP, your network must use the lesser of the two security standards (WEP). If you want to use the more robust WPA or WPA2 security, you must ensure that all the devices on your wireless network support WPA. Because WEP is easily broken and the specific WEP implementations vary among manufacturers, I recommend using only devices that support WPA or WPA2.

Management and DHCP Support

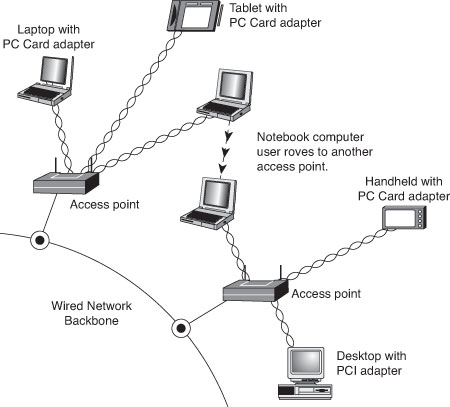

Most wireless access points can be managed via a web browser and provide diagnostic and monitoring tools to help you optimize the positioning of access points. Most products feature support for Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP), allowing a user to move from one subnet to another without difficulties.

The following image illustrates how a typical IEEE 802.11 wireless network uses multiple access points.

As you can see, as users with wireless NICs move from one office to another, the roaming feature of the NIC automatically switches from one access point toanother, permitting seamless network connectivity without wires or logging off the network and reconnecting.

Users per Access Point

The number of users per access point varies with the product; Wi-Fi access points are available in capacities supporting anywhere from 15 to as many as 254 users. You should contact the vendor of your preferred Wi-Fi access point device for details.

Although wired Ethernet networks are still the least expensive networks to build if you can do your own wiring, Wi-Fi networking is now cost-competitive with wired Ethernet networks when the cost of a professional wiring job is figured into the overall expense.

Because Wi-Fi is a true standard, you can mix and match access point and wireless NIC hardware to meet your desired price, performance, and feature requirements for your wireless network, just as you can for conventional Ethernet networks, provided you match up frequency bands or use dual-band hardware.

Current page: Wireless Network Logical Topologies

Prev Page Wireless Ethernet Hardware Next Page Putting Your Network TogetherDon Woligroski was a former senior hardware editor for Tom's Hardware. He has covered a wide range of PC hardware topics, including CPUs, GPUs, system building, and emerging technologies.

-

KelvinTy O... I thought all CAT5 are able to transmit 1000Mbps signals BEFORE reading this article... It's kind of weird ~_~" that I can get 5.X MB/s download speed = ="Reply -

Reynod Don could you talk to Chris A and Joe and see if we could give a few hard copies of this book away as prizes for some of our users here in the forums who work hard to help others?Reply

How about a copy for each of the users who make the top ranks for the month of November ... under the Hardware sections of the forums?

:) -

JasonAkkerman They make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.Reply -

xx_pemdas_xx JasonAkkermanThey make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.I got talked into making 10...Reply

-

spookyman JasonAkkermanThey make it look like making a cable it so easy, and it is, after the first few tries. Also, making one or two cables isn't too bad, but don't let yourself get talked into making 50 two foot patch cables. Your finger tips will never forgive you.Reply

Oh I don't know. I have made several thousand patch cord over the past 18 years.

All you need is a high quality crimper, good cutters and small screw driver. You are set.

-

silveralien81 This was a great article. In fact it inspired me to buy the book. I'm happy to report that the rest of the book is just as well written. Very educational. A top notch reference.Reply -

neiroatopelcc Read the first page. Seems like well written stuff, but not exactly written for my type of user. Also it seems to be igoring a lot of stuff. For instance it sais the network runs at the speed of the slowest component and will figure it out on its own. This isn't true. If you run a pair of 1000TX capable nics on old cat 5 cable (without the e), it'll still attempt to run at that speed, despite the massive crc errors it might generate. Also, if you're running on 'old gigabit hardware' it won't nessecarily have support for 10Base-T speeds. Also, not all firmware has autonegotiate or automdix support, thus you sometimes have to specificly set the speed between links. This is mainly for fiber links though, which seem to have been ignored entirely.Reply

Anyway. As I said, I think it's well written and probably quite suitable for people who don't know anything about networks (except it seems to assume people know the osi model). I'll go see if the other chapters are equaly basic.