IDF Spring 2006: Will Intel's Core Architecture Close the Technology Gap?

Intel's Energy Awakening

Intel finally admits that NetBurst was all but ideal. Justin Rattner said: "We were under tremendous competitive pressure."

If you are aware of recent processor history, Intel's new strategy is a very logical reaction. Pentium 4 and Pentium D processors draw more power than their AMD counterparts the Athlon 64 and Athlon 64 X2. This translates into higher cooling requirements and a higher energy bill. As soon as systems run 24/7, this difference easily adds up to $100 a year in North America or considerably more in countries with higher energy costs. Also think of large corporations with 100s or 1000s of systems: The energy cost difference can be a competitive disadvantage.

A simple reduction of the energy consumption could have been accomplished by taking the Pentium M or Core Duo architecture (Yonah core) and speeding it up in order to match Pentium 4 performance. However, Intel seems to do it right, as it defined a new equation for performance based on Energy per Instruction (EPI):

Performance = Frequency * Instructions per clock cycle

At last year's fall IDF, the announcement was to beat the competitor both in absolute performance and in performance per Watt. Intel changed that statement even more and talked about "satisfaction per Watt," which brings all the current processor features such as 64-bit capability and virtualization technology into the equation. In the end, it all comes down to delivering as much value as possible per clock cycle without involving ridiculous thermals.

And Intel goes a step further: It does not matter how long the processor pipeline actually is, it does not matter whether the memory controller is integrated or not, and it does not matter what clock speed the device actually is running at. All that matters is to deliver maximum performance at minimum power requirements. It does sound good, doesn't it? What we want now is proof.

Consuming less energy per instruction is the primary goal now. Interestingly, the Pentium M and Core Duo processors offer the same, low-level power consumption per instruction as the initial Pentium processor (P54).

Stay On the Cutting Edge: Get the Tom's Hardware Newsletter

Join the experts who read Tom's Hardware for the inside track on enthusiast PC tech news — and have for over 25 years. We'll send breaking news and in-depth reviews of CPUs, GPUs, AI, maker hardware and more straight to your inbox.

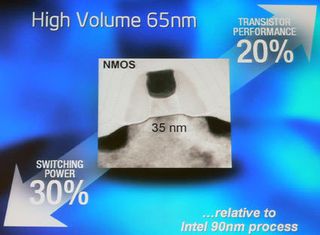

One important ingredient is the 65-nm manufacturing process that Intel describes as allowing for 20% faster transistors while requiring 30% less power. This, by the way, is also the projection the firm has for its introduction of 45-nm manufacturing late next year.

This makes pretty clear what happened with the P4 family: Increasing clock speed and voltage by 20% would improve performance only a little, but power draw would increase by three-fourths.

Current page: Intel's Energy Awakening

Prev Page IDF Spring 2006: The Core Of Intel 3.0 Next Page Quad Cores In Multi-Chip Packages By 2007Most Popular