Intel's Annual Report Indicates Second-Gen 3D XPoint Might be Delayed Until 2021

Annual Report also discusses shortages and Habana.

According to comments in Intel’s annual report, the company’s second-generation 3D XPoint products – Alder Stream and Barlow Pass – might be delayed until 2021. Intel also admitted in the report that the increases in wafer capacity did not lead to the desired increase in CPU output.

Second-Generation 3D XPoint

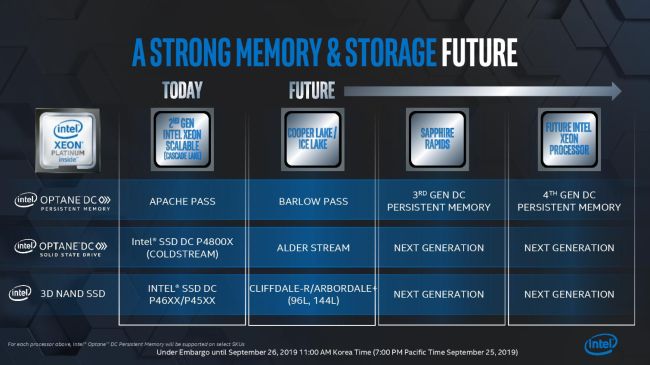

Intel 2018, Intel and Micron had announced that the the companies would cease co-development of 3D XPoint after the second generation was completed, which at the time was expected to happen by the second half of 2019. At an event in September last year, subsequently, Intel announced its second-generation 3D XPoint and provided a roadmap into the future.

In general, the second-generation 3D XPoint memory would features four layers of the memory, as opposed to two layers in the first generation. This will double its density, but Intel has also teased significant performance important.

The company planned to launch Barlow Pass as second-generation Optane DC persistent memory and Alder Stream Optane DC SSD. The roadmap indicated that the products would launch together with the Whitley platform, which will see Cooper Lake in the first half of the year followed by Ice Lake at the end of the year.

However, comments in Intel’s annual report (PDF) suggest that those products might not be released in 2020 at all. Intel says that the company will only ship (engineering) samples of Alder Stream in 2020, while Barlow Pass will achieve PRQ this year with no indication about shipments. Intel’s 144-layer 3D NAND still remains scheduled for 2020, however.

Describing the memory part of its six pillars of innovation, Intel says:

“With our Intel 3D NAND technology and Intel® Optane technology, we are developing products to disrupt the memory and storage hierarchy. The 4th generation of Intel-based SSDs are scheduled to launch in 2020 with 144-layer QLC memory technology. These SSDs are also Intel’s first NAND memory technology created independently by Intel since the conclusion of our partnership with Micron Technology, Inc. (Micron). The 2nd generation Intel Optane SSDs for data centers are scheduled to start shipping samples in 2020, and are designed to deliver three times the throughput while reducing application latency by four times. In addition, the second generation Intel Optane DC persistent memory is expected to achieve PRQ in 2020, and is designed for use with our future Intel Xeon CPUs.”

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Alder Stream

Intel’s commitment to merely ship samples of Alder Stream this year seems a strong indication that the second-generation Optane SSD might not see a broad launch until 2021.

For comparison, Intel said recently that Ice Lake-SP is already sampling to customers, but volume production will only start at some point in the first half of this year, with production shipments to customers in the “latter part of 2020.”

Nevertheless, Intel's statement that Alder Stream is "scheduled to start shipping samples in 2020" seems to contradict our earlier report that the SSDs have already started sampling. As we also detailed, Alder Stream supports PCIe 4.0, but Intel does not currently have CPUs that support it. (That might not be a problem, though, given that Intel says Ice Lake is also sampling.)

Intel did provide some performance expectations for Alder Stream: it will have three times higher throughput and four times lower latency.

Barlow Pass

Intel is a bit more ambiguous about Barlow Pass, Intel’s second-generation Optane persistent memory. (Persistent memory uses the DIMM form factor and the first-generation Apache Pass launched with Cascade Lake last year.)

It will achieve PRQ in 2020, according to Intel. Intel defines PRQ, short for Product Release Qualification as follows: “[PRQ] is the milestone when costs to manufacture a product are included in inventory valuation.”

In other words, it means that the product is qualified and can begin shipping to customers. So while Barlow Pass is expected to hit PRQ, Intel didn’t specify if it will begin shipping in 2020 already. Nevertheless, it indicates that Intel likely does not expect to ship higher volumes until 2021.

For comparison, Ice Lake was qualified in the second quarter of 2019, started shipping to OEMs in June, and it didn’t hit the shelves until September.

Design Rule Simplification, Supply Headwinds

Aside from its financials, Intel also discussed several other new items in its annual report.

On the process technology and manufacturing side, Intel discussed the shortages and the role of the design rules for 7nm.

Intel explained why the 25% increase in 14nm wafer capacity merely resulted in a low double-digit (10-15%) increase in PC supply. Intel attributed this to higher model volume, larger die sizes and more14nm chipsets (which continued to move from 22nm):

“We increased our wafer capacity [by 25%] during 2019; however, we did not see a commensurate increase in client CPU unit as wafer capacity was largely consumed by increases in modem and chipset volumes, and unit die sizes.”

Concerning process technology, Intel highlighted the company’s efforts to reduce the amount of design rules:

“We are also pursuing [a 4x] design simplification to accelerate innovation, including a significant reduction of design rules for future process nodes, to allow us to deliver the best solutions for our customer.”

The simplification in design rules can be attributed to the move to EUV at 7nm, which eliminates the need for expensive and complex multiple patterning lithography. Intel had already mentioned this at its investor meeting last year, but the fact that Intel would highlight in its annual report that it is reducing the amount of design rules, indicates that Intel sees this as a major factor in the progress it is making on 7nm.

Security Architecture Group and Habana

Concerning the security part of its six pillars, Intel hinted at the creation of a new group: “We continue to make significant investments in security technologies. We created the Intel Security Architecture and Technologies Group to serve as a center for security architecture across our products to design world class product security architecture for the years ahead.”

Intel had previously established the Product Assurance and Security Group in the aftermath of Meltdown and Spectre.

Lastly, Intel discussed the recent acquisition of Habana Labs:

"Habana's Gaudi AI training processor is currently sampling with select hyperscale customers. Large-node training systems based on Gaudi are expected to deliver up to four times increase in throughput versus systems built with the equivalent number of GPUs. The acquisition strengthens our AI portfolio and accelerates our efforts in the nascent, fast-growing AI silicon market."

Given that the company specifically mentions the Gaudi accelerator (and not Goya for inference), could indicate that Intel was mostly interested in Habana’s accelerator for training, perhaps because the product is already gaining adoption with cloud customers.

Intel had said that Habana would continue to operate independently.

-

InvalidError It wouldn't be modern-day Intel without things getting delayed by a couple of years.Reply -

bit_user Reply

Well, their 14 nm products seem to launch on time. In that case, the delays don't come in to the picture until you actually try to order them.InvalidError said:It wouldn't be modern-day Intel without things getting delayed by a couple of years.

Let's see if their dGPUs launch on schedule. -

InvalidError Reply

Broadwell launched fashionably late and everything after Kaby Lake only exists because Intel needed something on the market while 10nm was "coming soon" like a horde of creeper zombies.bit_user said:Well, their 14 nm products seem to launch on time. -

bit_user ReplyIntel explained why the 25% increase in 14nm wafer capacity merely resulted in a low double-digit (10-15%) increase in PC supply. Intel attributed this to higher model volume, larger die sizes and more14nm chipsets (which continued to move from 22nm)

That's what I've been saying. They had to add cores to keep up with AMD, which in turn hurts their supply crunch even more. -

bit_user Reply

Yes, I didn't think you were going back that far, because all of their Skylake-branded products were basically on-time.InvalidError said:Broadwell launched fashionably late

Be that as it may, they've been executing to their roadmaps, on launches of 14 nm products.InvalidError said:and everything after Kaby Lake only exists because Intel needed something on the market while 10nm was "coming soon" like a horde of creeper zombies.

The delays are all coming from 10 nm. -

InvalidError Reply

14nm products that were not meant to exist and are fundamentally the same Skylake as four years ago with some hardware fixes and more mature fab process. It would be highly problematic if Intel ran into any problems executing that.bit_user said:Be that as it may, they've been executing to their roadmaps, on launches of 14 nm products. -

bit_user Reply

Yeah, I get it. They represent a strategic fallback position that wouldn't have been needed if Intel could've executed on their 10 nm plans.InvalidError said:14nm products that were not meant to exist

However, you seem to be spinning a story where Intel literally can't execute on anything, whereas the reality is really just that specifically their 10 nm has been a disaster.

Intel has been rolling out new low-power cores, and their Gen 11 UHD iGPUs launched on schedule. The place hasn't fallen utterly to pieces. Not yet, at least.InvalidError said:It would be highly problematic if Intel ran into any problems executing that. -

InvalidError Reply

Successfully executing steppings/re-spins of Skylake for four "generations" isn't much of a technical or engineering feat. That's basement level expectations compared to how Intel used to successfully execute simultaneous node and architecture upgrades. It hasn't done either in a particularly meaningful way in four years. Yes, it added extra cores in the last two (soon to be three) generations, but that is little more than a copy-paste exercise in a ring-bus architecture.bit_user said:However, you seem to be spinning a story where Intel literally can't execute on anything, whereas the reality is really just that specifically their 10 nm has been a disaster.

Ice Lake isn't on schedule, the first time Intel put Ice Lake on a road map, it was supposed to launch two years ago.bit_user said:Intel has been rolling out new low-power cores, and their Gen 11 UHD iGPUs launched on schedule. -

bit_user Reply

If you want to undermine my point, try citing something that slipped which isn't made on their 10 nm process.InvalidError said:Ice Lake isn't on schedule, the first time Intel put Ice Lake on a road map, it was supposed to launch two years ago. -

spongiemaster ReplyInvalidError said:Successfully executing steppings/re-spins of Skylake for four "generations" isn't much of a technical or engineering feat. That's basement level expectations compared to how Intel used to successfully execute simultaneous node and architecture upgrades. It hasn't done either in a particularly meaningful way in four years. Yes, it added extra cores in the last two (soon to be three) generations, but that is little more than a copy-paste exercise in a ring-bus architecture.

The architecture hasn't changed much, but the node optimizations weren't trivial. The Intel engineers have really accomplished something getting 8 core mainstream (ie high volume) CPU's up to 5GHz on 14nm. Rumors are that they'll make it to 10 cores at 5GHz before they get to 10nm.

Ice Lake isn't on schedule, the first time Intel put Ice Lake on a road map, it was supposed to launch two years ago.

I think you're confusing Cannon Lake with Ice Lake. Cannon Lake had one token CPU sku released about 18 months ago so Intel could claim they were shipping 10nm. Ice Lake was not on roadmaps 3 or 4 years ago.