GeForce GTX 680 2 GB Review: Kepler Sends Tahiti On Vacation

Enthusiasts want to know about Nvidia's next-generation architecture so badly that they broke into our content management system and took the data to be used for today's launch. Now we can really answer how Kepler fares against AMD's GCN architecture.

PCI Express 3.0 And Adaptive V-Sync

PCI Express 3.0: One Last Perf Point

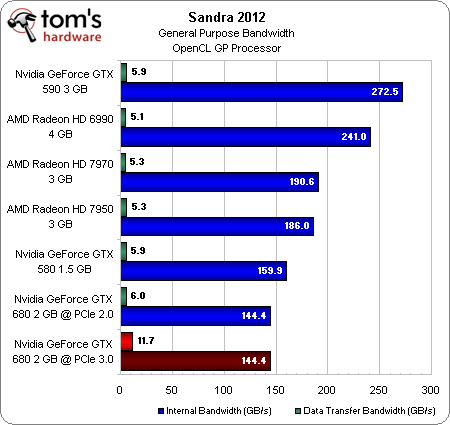

GeForce GTX 680 includes a 16-lane PCI Express interface, just like almost every other graphics card we’ve reviewed in the last seven or so years. However, it’s one of the first boards with third-gen support. All six Radeon HD 7000 family members preempt the GeForce GTX 680 in this regard. But we already know that, in today’s games, doubling the data rate of a bus that isn’t currently saturated doesn’t impact performance very much.

Nevertheless PCI Express 3.0 support becomes a more important discussion point here because Nvidia’s press driver doesn’t enable it on X79-based platforms. The company’s official stance is that the card is gen-three-capable, but that X79 Express is only validated for second-gen data rates. Drop it into an Ivy Bridge-based system, though, and it should immediately enable 8 GT/s transfer speeds.

Nvidia sent us an updated driver to prove that GeForce GTX 680 does work, and indeed, data transfer bandwidth shot up to almost 12 GB/s. Should Nvidia validate GTX 680 on X79, a new driver should be the answer. In contrast, the data bandwidth of AMD’s Radeon HD 7900s slides back from what we’ve seen in previous reviews. Neither AMD nor Gigabyte is able to explain why this is happening.

Adaptive V-Sync: Smooth Is Good

When we benchmark games, we’re perpetually looking for ways to turn off vertical synchronization, or v-sync, which creates a relationship between our monitors’ refresh and graphics card frame rate. By locking our frame rate to 60 FPS on a 60 Hz LCD, for example, we wouldn’t be conveying the potential performance of a high-end graphics card capable of averaging 90 or 100 FPS. In most titles, turning off v-sync is a simple switch. In others, we have to hack our way around the feature to make the game testable.

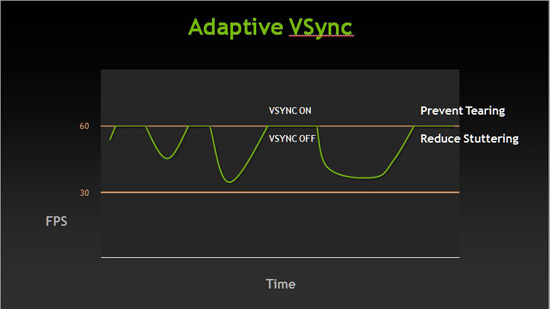

In the real world, however, you want to use v-sync to prevent tearing—an artifact that occurs when in-game frame rates are higher than the display’s refresh and you show more than one frame on the screen at a time. Tearing bothers gamers to varying degrees. However, if you own a card capable of keeping you above a 60 FPS minimum, there’s really no downside to turning v-sync on.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Dropping under 60 FPS is where you run into problems. Because the technology is synchronizing the graphics card output with a fixed refresh, anything below 60 Hz has to still be a multiple of 60. So, running at 47 frames per second, for instance, actually forces you down to 30 FPS. The transition from 60 to 30 manifests on-screen as a slight stutter. Again, the degree to which this bothers you during game play is going to vary. If you know where and when to expect the stutter, though, spotting it is pretty easy.

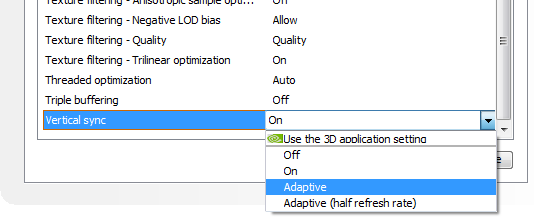

Nvidia’s solution to the pitfalls of running with v-sync on or off is called adaptive v-sync. Basically, any time your card pushes more than 60 FPS, v-sync remains enabled. When the frame rate drops below that barrier, v-sync is turned off to prevent stuttering. The 300.99 driver provided with press boards enables adaptive V-sync through a drop-down menu that also contains settings for turning v-sync on or off.

Given limited time for testing, I was only really able to play a handful of games with and without v-sync, and then using adaptive v-sync. The tearing effect with v-sync turned off is the most distracting artifact. I’m less bothered when v-sync is on. Though, to be honest, it takes a title like Crysis 2 at Ultra quality to bounce above and below 60 FPS with any regularity on a GeForce GTX 680.

Overall, I’d call adaptive v-sync a good option to have, particularly as it permeates slower models in Nvidia’s line-up, which are more likely to spend time under the threshold of a display’s native refresh rate.

Current page: PCI Express 3.0 And Adaptive V-Sync

Prev Page Overclocking: I Want More Than GPU Boost Next Page Hardware Setup And Benchmarks-

outlw6669 Nice results, this is how the transition to 28nm should be.Reply

Now we just need prices to start dropping, although significant drops will probably not come until the GK110 is released :/ -

Scotty99 Its a midrange card, anyone who disagrees is plain wrong. Thats not to say its a bad card, what happened here is nvidia is so far ahead of AMD in tech that the mid range card purposed to fill the 560ti in the lineup actually competed with AMD's flagship. If you dont believe me that is fine, you will see in a couple months when the actual flagship comes out, the ones with the 384 bit interface.Reply -

Chainzsaw Wow not too bad. Looks like the 680 is actually cheaper than the 7970 right now, about 50$, and generally beats the 7970, but obviously not at everything.Reply

Good going Nvidia... -

rantoc 2x of thoose ordered and will be delivered tomorrow, will be a nice geeky weekend for sure =)Reply