Extreme Overclocking: 10 Ryzen CPUs Under LN2

Lapping The CPU

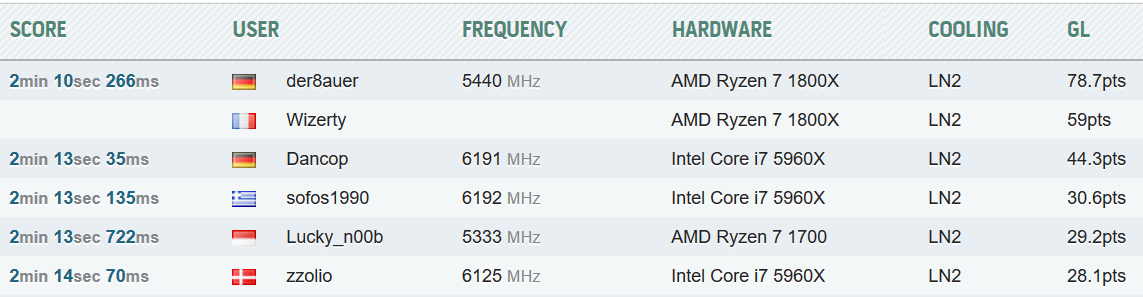

As we ran our tests, we realized that this sample was above average. So, we tried to land a record for eight-core processors, including AMD and Intel CPUs. The combat was relentless. On one hand, there were some very good results obtained by overclockers right around the time Ryzen was released, and it isn't hard to imagine that they had access to a sizeable quantity of hand-picked chips. On the other hand, Intel's Core i7-5960X compensates for its age with frequencies beyond 6 GHz under liquid nitrogen cooling.

We therefore decided to concentrate our efforts on two benchmarks: Cinebench R15 and GPUPI. In both cases, we succeeded in taking second place, in front of the -5960X contenders running around 6200 MHz (in the case of GPUPI).

Lapping In Pursuit Of MHz

At that time, our highest clock speed in GPUPI was 5390 MHz. The leader, Der8auer, was at 5440 MHz. First place, while so close, seemed out of reach. Without a better 1800X at our disposal, we decided to lap our sample in the hopes of better thermal transfer.

During our tests, we saw a gain of 2.7 MHz/°C at -196°C. If lapping helped us gain 15°C, which is not impossible given the high voltages we were using, 5430 MHz should be attainable.

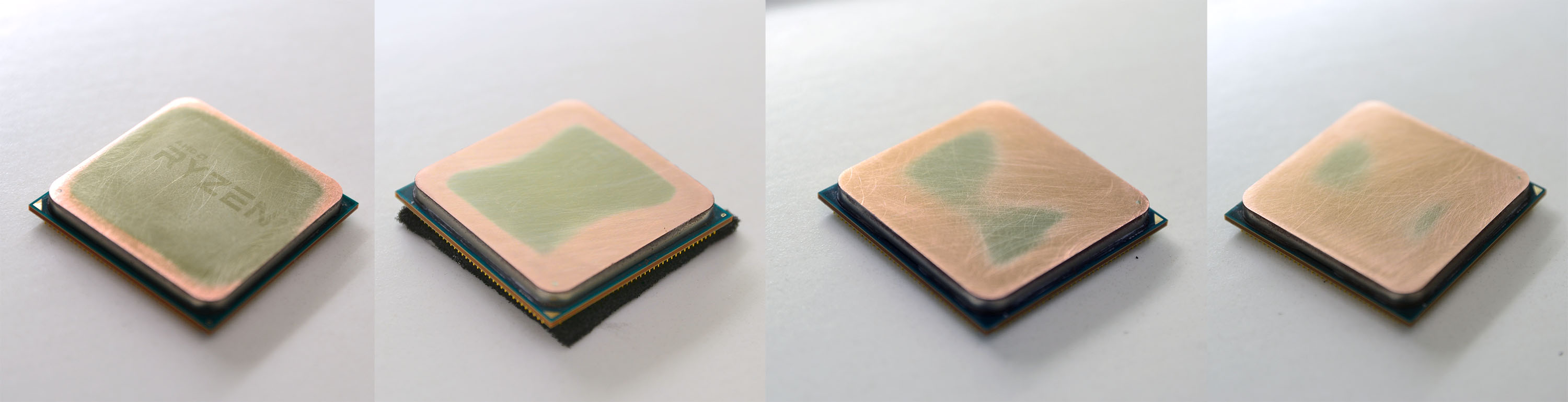

The process proved more laborious than we expected. Within the first few minutes, defects began appearing in the CPU lid's shape. A flat processor should be “worn” completely on the surface in a homogeneous manner. However, we were uniquely attacking the edges of the IHS.

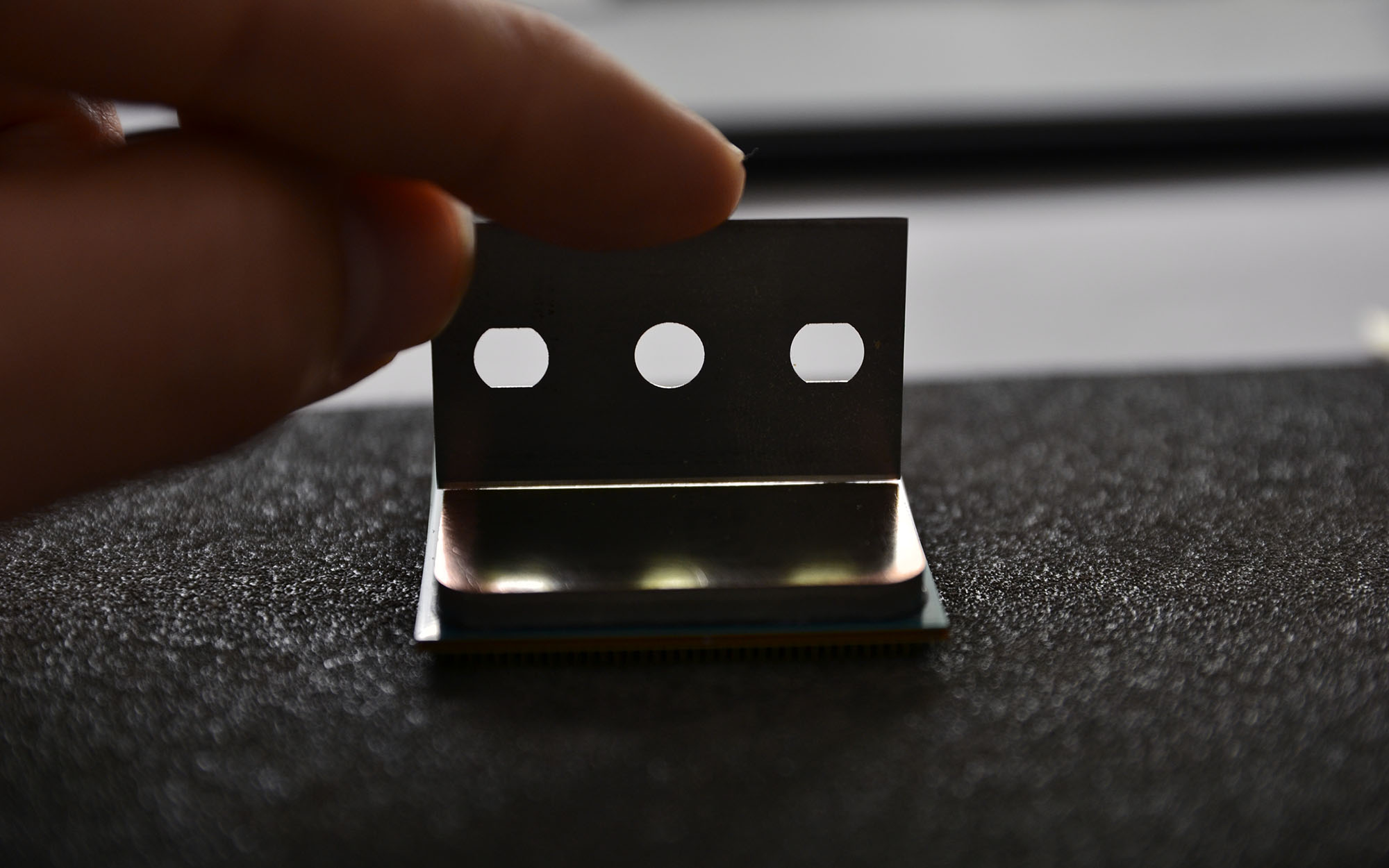

There were two possible scenarios: either the processor was not actually flat, or we were lapping incorrectly. To remove any doubt, we took a brand new razor blade and placed it on the CPU's surface. There it was: the blade only touched the borders, allowing a seam of light to shine through in the center.

Our lapping effort resumed. We used emery cloth (comparable to sand paper and intended for use in sanding metals) attached to a piece of glass to guarantee a uniform surface. We started with a course grit to rapidly remove (relatively, of course) the extra material on the edges.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

This is the progress we made in one hour. The nickel coating is removed, revealing copper on the sides. Gradually as we eroded the surplus material, our uniform area grew in size. In the end, almost the entire IHS appears to be copper. Two visible spots persist, but the defect is sufficiently small to be ignored. The processor doesn't need to be polished any further. Having a flat surface is top priority. Fine scratches won't affect performance.

At this point, we resumed our trials with liquid nitrogen, confident in our work and hopeful that we'd realize our estimated gains.

MORE: Best CPUs

MORE: How To Overclock AMD Ryzen CPUs

MORE: De-Lidding and Overclocking Core i7-7700K

MORE: CPU Overclocking Guide: How (and Why) to Tweak Your Processor

Current page: Lapping The CPU

Prev Page 1800X: First Test Of Scaling With LN2 Next Page BIOS Settings-

InvalidError It isn't surprising that the highest-end CPUs have the highest and least troublesome overclocks as that's what chip binning is for - the best dies go to the premium SKUs first, lower tiers get what is left over.Reply -

-Fran- Reply19937674 said:It isn't surprising that the highest-end CPUs have the highest and least troublesome overclocks as that's what chip binning is for - the best dies go to the premium SKUs first, lower tiers get what is left over.

Even more, it's very interesting since it gives some credibility that AMD is not binning due to defects, but electrical properties, hence, making the rumour mill of being able to unlock some 4C and 6C to higher core counts not that far-fetched.

Cheers! -

Wisecracker Très bon!Reply

(hope I used this correctly)

Just wondering ... would it be considered a 'faux pas' (or, an insult to AMD) to release the batch numbers?

-

theyeti87 Reply19937697 said:19937674 said:It isn't surprising that the highest-end CPUs have the highest and least troublesome overclocks as that's what chip binning is for - the best dies go to the premium SKUs first, lower tiers get what is left over.

Even more, it's very interesting since it gives some credibility that AMD is not binning due to defects, but electrical properties, hence, making the rumour mill of being able to unlock some 4C and 6C to higher core counts not that far-fetched.

Cheers!

Wasn't that a similar case with the Phenom X4, X3, and X2's? Or were those 3's and 2's disabled cores due to defect? -

-Fran- Reply19937706 said:19937697 said:19937674 said:It isn't surprising that the highest-end CPUs have the highest and least troublesome overclocks as that's what chip binning is for - the best dies go to the premium SKUs first, lower tiers get what is left over.

Even more, it's very interesting since it gives some credibility that AMD is not binning due to defects, but electrical properties, hence, making the rumour mill of being able to unlock some 4C and 6C to higher core counts not that far-fetched.

Cheers!

Wasn't that a similar case with the Phenom X4, X3, and X2's? Or were those 3's and 2's disabled cores due to defect?

They were a mix of both. If you were lucky (and could track down some of the batches) you were able to unlock the CPU with little worry, but there were defective ones that when unlocked, would not work. I came across both myself.

To be honest, I just catalog it as "interesting", because I will pay the difference to always get the full working version, but I do know there's people out there that like gambling and can track batch numbers :P

Cheers! -

InvalidError Reply

The relatively low defect rate has been a given since launch IMO: half of each CPU core is L2 cache and half of the CCX die area is the L3, so you have a 50% chance that defects within a CCX will land in L3. If the defect rate had been significant, cache defects would have forced AMD to launch models with 8MB of L3 long before the 1400.19937697 said:Even more, it's very interesting since it gives some credibility that AMD is not binning due to defects, but electrical properties -

-Fran- Reply19937880 said:

The relatively low defect rate has been a given since launch IMO: half of each CPU core is L2 cache and half of the CCX die area is the L3, so you have a 50% chance that defects within a CCX will land in L3. If the defect rate had been significant, cache defects would have forced AMD to launch models with 8MB of L3 long before the 1400.19937697 said:Even more, it's very interesting since it gives some credibility that AMD is not binning due to defects, but electrical properties

True. It's just nice to have more non-validated statistical-irrelevant proof! Haha.

Cheers! :P -

Gregory_3 This is all kind of cute, but the real market success will be played out in conventional liquid cooled and air cooled environments. Nobody is going be running high end software with condensation dripping all over.Reply -

InvalidError Reply

There wouldn't be condensation issues if OCers used the nitrogen gas boiling out of the pot to displace air and the moisture it contains around the motherboard to keep it off of it. Instead of circulating the boil-off around the motherboard though, LN2 OCers use fans to suck it away, drawing more moisture-ladden air in the area.19938043 said:Nobody is going be running high end software with condensation dripping all over.

-

gasaraki "It isn't surprising that the highest-end CPUs have the highest and least troublesome overclocks as that's what chip binning is for - the best dies go to the premium SKUs first, lower tiers get what is left over."Reply

While it might not be surprising, it shows the immaturity of the Ryzen processors in that the build quality is not the same between different CPUs or even CCXes and binning is what they do for the lower cored versions. If your build process was mature ALL your chips would come out mostly the same and "awesome" then at that point your forced to just shutdown cores to make the lower cored processors.