SanDisk Ultra Plus SSD Reviewed At 64, 128, And 256 GB

SanDisk's Ultra Plus replaces the company's older SATA 3Gb/s SandForce-based Ultra with something a bit more modern, and with a budget-oriented price tag. We test all three capacities to see if the entry-level pricing belies a pocket rocket in disguise.

Dissecting SanDisk's Ultra Plus SSD

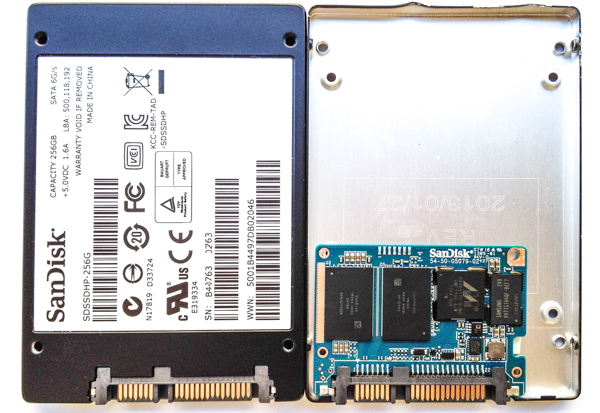

The very first thing you notice when you pick up an Ultra Plus is its weight. And not because it weighs a ton. Rather, it feels like it's packed with goose down or silly string. Seriously, this is as light as a 2.5" SSD can get. That might be really convenient if you're going to send it into space, where every gram counts. However, it's a little disconcerting the first time you hold it in your hand (even for a seasoned veteran of solid-state storage like myself). Removing the four screws hiding behind the rear label allows us to pop the drive open and see the reason for the Ultra Plus' abnormal lightness.

The 2.5", 7 mm z-height chassis hides a truly diminutive PCB. Not much bigger than an mSATA drive, it'd be difficult to make a solid-state device any smaller with a full-sized SATA interface. It's also worth noting that the top housing is metal, but only in the same way that the tin foil used to wrap bubble gum is metal. Look closely and you can tell that the top housing of our sample is bent up a little bit. It's best not to get too boisterous with a chassis sporting the structural integrity of al dente pasta.

It does the job SanDisk needs it to, though, and frankly matches the style employed by most other SanDisk SSDs. It doesn't get many style points. We know what's on the inside counts most though, so let's take a closer look at the PCB.

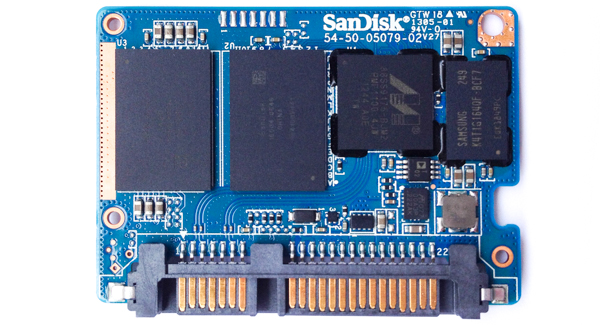

This 256 GB Ultra Plus has four NAND emplacements. Two on the front, two on the back. The 19 nm Toggle-mode NAND comes from the Chinese fabs that SanDisk and Toshiba share. It utilizes SanDisk's All Bit Line architecture, which theoretically allows for more NAND parallelism, since one memory device typically only has the ability to access half the bit lines simultaneously (a half bit line architecture). Naming aside, the NAND is supposedly rated for 3000 P/E cycles, putting it on par with the majority of consumer drives today.

The thermal demands of mobile computing mean that SSDs tend to get quite toasty at times. To keep this from becoming an issue, the Ultra Plus throttles if its flash gets too hot. The effect is a reduction in write speed as the hardware cools down, though it doesn't kick in until past 60 degrees Celsius. You'll probably never see SanDisk's safety mechanism trigger on a desktop; it's more targeted to notebooks. If it does become necessary, though, the NAND-saving feature could be a real boon. Flash characteristics change at higher temperatures, and endurance can suffer as a result. Write and erase operations require more power than read ops, and therefore thermal throttling is made effective by reducing write speed.

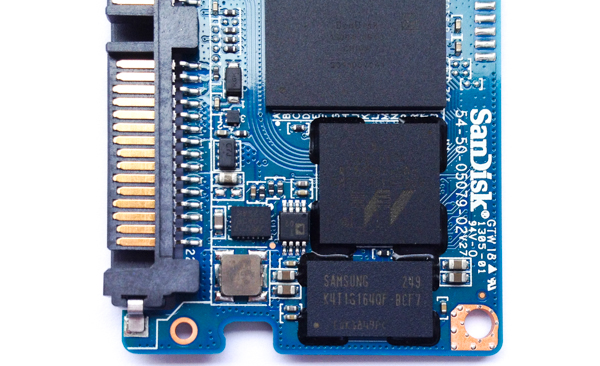

The silk screening is a bit difficult to decipher, but Marvell's 88SS9175-BJM2 controller is located just above the Samsung LPDDR2 DRAM package. A few drives employ DDR3 data caches, but the older Marvell processor's ARM architecture doesn't support the faster memory interface.

This 256 GB PCB has 128 MB of DRAM on-board. The 128 GB variant includes just 64 MB. As you can see in the picture above the DRAM and controller packages both get a touch of BGA under-filling.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Unlike the newer 88SS918x-series SSD processors from Marvell, the older design is limited to the SATA 3.0 specification. It's not a huge deal; however, version 3.1 allows TRIM commands to be queued, preventing halts while the drive sorts everything out. In 3.0, read and write commands are still queued, while TRIM is put off until the pause can be tolerated. The 3.1 spec changes that, though you'll probably never notice the difference. Most SSDs receive the TRIM command from the operating system and hold onto it for a while. Then, once the drive is good and ready, it TRIMs. Unless you force the operation, an SSD takes its sweet time, waiting until the drive drops to idle to do its business.

The back of the PCB holds a smattering of surface-mount components and the other two NAND emplacements.

Current page: Dissecting SanDisk's Ultra Plus SSD

Prev Page SanDisk's Ultra Plus: Ballin' On A Budget Next Page Test Setup And Benchmarks-

kevith I have had the former SanDisk Extreme 128 GB for a year now, and it´s definitely fast enough. But what´s more impressive is, that after a year, the write amplification still hovers between 0,800 and 0,805. I´m using it in my laptop for quite "normal" use, FB, YouTube, mail, wordprocessing etc.on Windows 8 64-bit. So far it has served me very well, my next SSD is going to be another SanDiskReply -

Soda-88 I recommended this SSD (256GB) to my friend just a week ago since it was nearly as cheap as top of the line 128GB SSDs, glad to read positive review.Reply -

alidan im honestly looking into ssd drives for games and mass small file storage.Reply

these are cheap, and they are large, would definitely help with load times/game performance, and browsing images stored enmass. -

Brian Fulmer I ordered 5 Extreme 128GB drives in March (model SDSSDHP-128G). I've been using OCZ, Kingston, Samsung and Crucial drives in every desktop and notebook I've deployed since August 2013. Out of ~75 drives, I've had 1 bad Vertex 4 and 6 defective by design Crucial V4's. Of the 5 SanDisks, 2 failed before deployment. Support was laughably incompetent in demanding the drives be updated with the latest firmware. Their character mode updater couldn't see the drives, because they DIED. SanDisk is no longer on my buy list.Reply

Incidentally, of the 8 SSD model SSD P5 128GB, I've had one die. The context should be of 35 Vertex 4's, I've had one die. I've had zero failures with 15 840's despite their supposedly fragile design. -

ssdpro Brian Fulmer's comments are very reasonable (except the "deployed since Aug 2013" part lol). Way too many people experience a failure then scream all drives from that mfg are junk. I have owned 2 840 Pro drives and had one fault out. Does that mean Samsung drives have a 50 percent failure rate? For me, yes, but overall no and I am definitely not that naive. The 840 Pro can and do fail like anything electrical can. I have owned probably a dozen OCZ drives and had one Vertex 2 failure - does that mean OCZ/SandForce firmware stinks and they aren't reliable? No, it just means a drive died and who knows why. I have owned a couple SanDisk products and none failed. Does that mean SanDisk is the best? No... it just means I didn't have one die but I also only sampled 2.Reply -

Combat Wombat These and the OCZ drives from newegg are looking mighty close in price!Reply

BF4 Rebuild is about to take place :D -

@ssdpro: spot on. sure, if i buy from vendor a and his product fails, i will probably not buy from him again. if it fails more than once, there is no chance i'll buy his stuff again and i also will warn others about it. but understandable as this is, in the end even that doesn't mean much about the reliability of the manufacturer.Reply

that's also why i'm a bit sceptical about product ratings on amazon and the likes, since people are more inclined to complain about a bad experience, than share their view on a product that simply does what it should do: work.

what we would need more often are statistics from bigger companies, or even repair services, so we don't have to base our purchases on samples of a few dozen to a few hundreds, but on thousands upon thousands of cases. -

flong777 The 840 Pro still appears to be the fastest overall SSD on the planet - but the difference between the top 5 is pretty much negligible. Among the top five, reliability and cost become the determining factors.Reply -

anything4this I don't understand the ~500MBs read limit on the drives. Is it an interface bottleneck?Reply