Gigabit Wireless? Five 802.11ac Routers, Benchmarked

Five years ago, we didn't have homes with a dozen wireless nodes and the need to run HD video to multiple screens. Today we do. Our 802.11n networks, especially on the 2.4 GHz band, are swamped. Can 802.11ac save the day? We test six routers to find out.

802.11ac: The Beginning

Why you can trust Tom's Hardware

At some point, every modern freeway was a dream to drive. The pavement was fresh and the lanes were all but empty. But inevitably, congestion set in. People learned to hop on the freeway to quicken their daily travel needs. As populations steadily grew, so did the number of cars clogging the streets. What was once a breezy late afternoon jaunt eventually became today’s four-hour exercise in asthmatic gridlock.

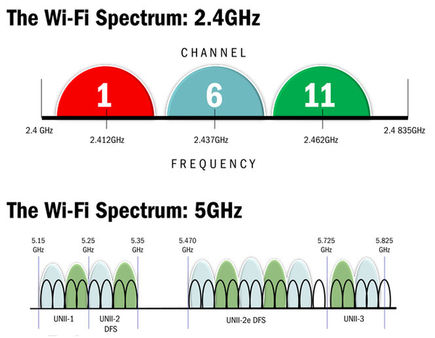

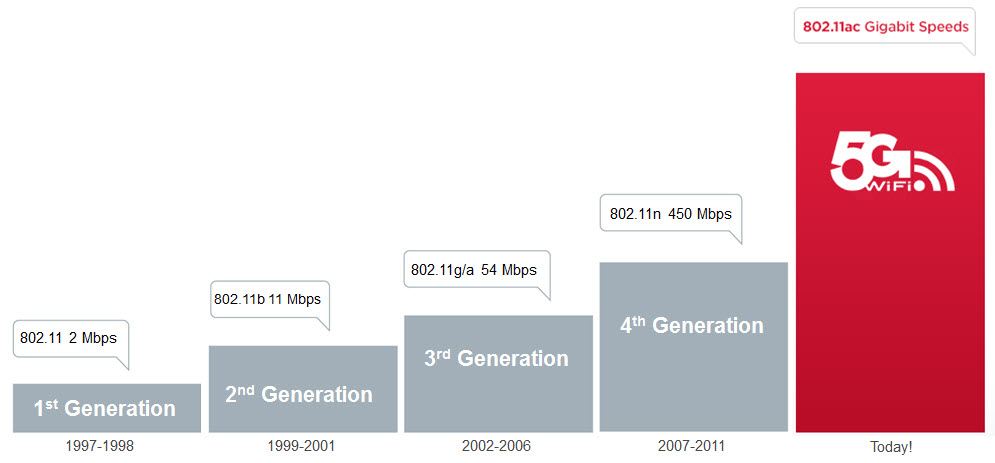

Automotive analogy aside, we’re really talking about the 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi spectrum. In the first days of 802.11b (circa 1999), the freeway may have posted a paltry 11 Mb/s, but there was hardly anyone else on the road. Fast forward to the present. Despite evolving through 802.11g and 802.11n, the 2.4 GHz band became a congested mess clogged with notebooks, netbooks, wireless speakers, Bluetooth peripherals, smartphones, tablets, set-tops, TVs, consoles, appliances, and all manner of other devices. These gadgets compete for what boils down to essentially three (after considering bandwidth overlap) possible transmission channels under 802.11b. A 20 MHz-wide 802.11g/n network has four such channels, while a 40 MHz-wide 802.11n network has just two.

True enough, 802.11a, which resides on the 5.0 GHz band, offers more non-overlapping channels (23, to be exact). While 802.11a offered comparable 54 Mb/s speeds to 802.11g, the 2.4 GHz solution won out in the market thanks to the fact that longer wavelengths have better ability to pass through obstructions. With an oscillation roughly twice that of 2.4 GHz, a 5.0 GHz signal was more likely to die in less distance than its competitor, and so 802.11b/g went on to become the dominant public wireless communication standard. By the time 802.11n arrived supporting both radio bands, wireless had become so popular that interference and congestion was a significant problem for many users. While 802.11n employed several technologies to help improve wireless performance, it was clear that the 2.4 GHz band was becoming ever more bogged down. For a more thorough look at these problems and some of 11n’s answers to them, we strongly recommend reviewing our two-part series, Why Your Wi-Fi Sucks and How It Can Be Helped and What To Do About It.

Today, the successor to 802.11n, dubbed 802.11ac, is far enough down the road of standardization that vendors have the confidence to start releasing product. At present, 802.11ac is working under Draft 4.0. The 802.11 Working Group expects the standard to be finally approved by late 2013, although by then the technology will already be pervasive in the market.

The first 802.11ac chipset, from Quantenna, began shipping in November 2011. In April 2012, Netgear arrived with the first 802.11ac consumer router, fueled by Broadcom innards. Other vendors soon followed. By the end of 2013, we expect mid- to high-end consumer routers to have completely switched over from 802.11n.

But for now, 11ac is new, still relatively scarce, and priced accordingly. Is it worth it? We’ve seen pre-standard Wi-Fi advances that didn’t merit their price tags in the past. Are we in for another round of disappointment, or is today’s price premium for 11ac a bargain for the performance boost? We only know of one way to find out.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

-

boulbox Well, i can't wait until i can make my router give wifi all the way to my to my work area.(only a few blocks away)Reply -

I've tested both the R6300 and the RT-AC66U in my home. The R6300 beats it hands down. The average homes won't have the traffic that your artificial software creates. Even your tests show that R6300 in 5ghz mode is faster. People will buy these for gaming and HD movie viewing and the R6300 has better range as well. I've paired my R6300 with an ASUS PCE-AC66 desktop wireless AC adapter and I can acheive 30 MB/S (megabytes) to my HTPC in a 2 story house. That's an insane speed. The RT-AC66U only managed about 15 to 18 MB/s. Also make sure the R6300 has the latest firmware, which is V1.0.2.38_1.0.33. But in conclusion, the R6300 and the RT-AC66U are like a SRT Viper and ZR1 Vette. They are both great pieces of hardware to fit most users needs. Get the ASUS If you got a ton of traffic and a lot of 2.4 ghz devices. Grab the R6300 if you are looking for a friendly setup, max speed, and max range.Reply

-

fwupow Man it sure sucks when you type a long comment and it gets vaporized cuz you weren't logged in.Reply -

DeusAres I'd be happy with a 2Mb/s connection. It'd be better than this horrible 512 Kb/s connection I have now. At least then, I may actually be able to watch youtube vids in 360p.Reply -

fwupow Here's the gist of what I typed before it was rudely vaporized.Reply

I have a dual-band router (Netgear N600). I also purchased a couple of dual-band client USB adapters Linksys AE2500 or something to that effect.

So the USB adapter works fine for a desktop, but having that crap sticking out the side of a laptop, netbook or tablet? Busted in 10 minutes. I hooked one up to my netbook and fried it within a couple of weeks because I'm a Netbook in bed guy. You wouldn't think it could get so hot from a USB port but it does.

So the reality is that you have all these devices that can't be upgraded to dual-band and enjoy very little if any benefit from the new-fangled dual-band router.

The other beef I have with routers is that they're terrible with the way they split up bandwidth between multiple devices. Instead of responsively reassigning bandwidth to the device that needs it, the router continues to reserve a major slice for a device that I'm not using.

If you live in an apartment building, it's actually rather rude to use the full 300Mbps capacity of the wireless N band, since you may well succeed in effectively shutting your neighbor down. There's so much happening in the 2.4GHz band nowadays, it's unreal. Your own cordless keyboards/mice/controllers etc can malfunction from being unable to get a packet in edgewise.

For these dual-band routers to be really useful, we need manufacturers of smartphones, tablets, laptops, netbook and such to build dual-band clients into them because adding the functionality with some sort of dongle just doesn't work. -

memadmax I was a 802.11g and n "adoption" tester....Reply

Never again...

I'll give ac a year or two before I jump on it... -

SteelCity1981 my wireless N produces 300 Megabits which would equal around 37 Megabytes. My highspeed internet doesn't come cloe to reaching 37 megabytes and i don't transfer tons of files wirelesly and my wi-fi rangs is pretty good .So i'm perfectly fine with my 300MB N wireless router right now. Besides that none of my devices spport ac anyhow so it would get bottlenecked from reaching its full potential.Reply -

chuckchurch iknowhowtofixit"Folks, the time to start your 802.11ac adoption is now."I think this review proved that it is time to wait for 2nd generation wireless AC routers to appear before rushing to purchase.Reply

Exactly. The 'client' adapter they used if anyone didn't catch it was a Cisco/Linksys router-sized device. Not practical by any means. It'd be totally insane to make any product recommendations prior to real client adapters being available, or more accurately, embedded ones are available. I think a wireless salesman wrote this article.