The Worst Tech of the Last 10 Years

How many of these devices and technologies did you spend your money on?

Looking back at a decade of bad tech can be a fun experience--so long as you didn’t spend your own hard-earned money on too many of the products and technologies below. But even if you did, say, buy a power-hungry under-performing AMD FX processor or a potentially exploding Samsung Note 7, time and better tech have likely come along to ease your pain by now.

But if you’re still stuck with an Apple MacBook with a Butterfly keyboard now that there’s a much better option in the new 16-inch model, or you're still using your Surface RT tablet to brows the web, maybe check out our feature on the most influential tech of the past decade for a more positive look back at the 2010s.

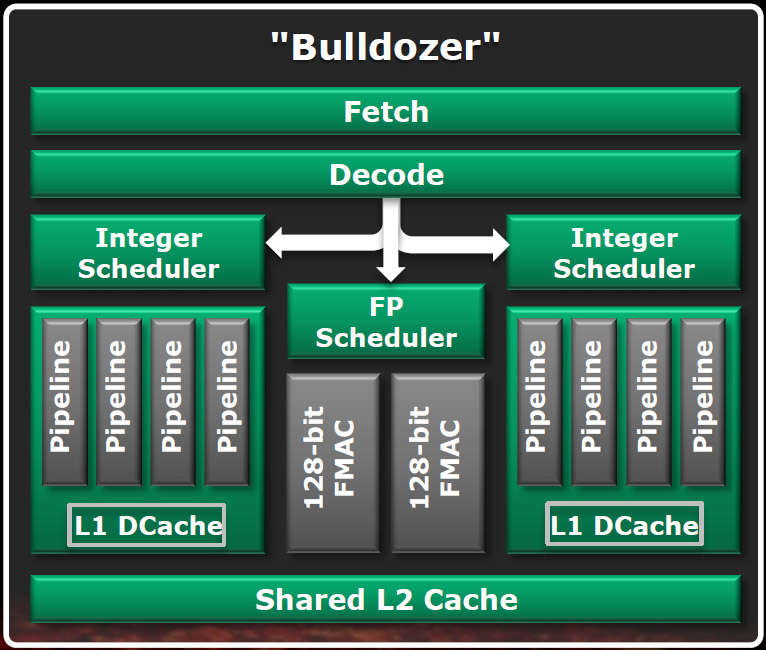

And try to look on the bright side: Failures often force big companies to truly innovate, which means better tech for all of us down the line. Sometimes the tech world just needs to work some bad ideas out of its system the hard way. Would we have ever gotten the excellence that is the Zen architecture without the pain of Bulldozer? Would big-name companies still be trying to convince us that Android and Linux are viable gaming platforms without the major flameouts of Ouya and Steam Machines?

It’s tough to answer questions like that with any kind of certainty, but before we barrel into 2020, let’s take a quick look back in hindsight at the tech that didn’t work (or just didn’t sell) and try to figure out why--or just wonder the engineers and designers were thinking.

AMD Bulldozer

AMD’s Bulldozer launched to lackluster reviews back in 2011, and the following years found the company trying to right the ship with Piledriver, Steamroller, and Excavator. Meanwhile, Intel dominated the mobile, desktop, and server markets with seemingly-insurmountable performance built on the Sandy Bridge design and an unrelenting cadence of incremental improvements.

AMD’s Bulldozer failure doomed the desktop PC to a cadence of incremental upgrades for six long years as it remained mired at four cores, and it’s safe to say AMD’s processor portfolio didn’t regain its lost luster until the arrival of Zen in 2017.

-- Paul Alcorn

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

USB3 Nomenclature

Portable storage geeks were thrilled when we got USB 3.0 at the turn of the decade. Its 5Gbps transfer rate vastly shortened transfer times compared to the maximum 480Mbps USB 2.0 standard it supplanted, and further elation came just a few years later with the 10 Gbps of USB 3.1.

But then came the naming gimmicks: The industry started calling devices that operate at 5 Gbps USB 3.1 Gen1 and those which operate at 10 Gbps USB 3.1 Gen2. Now everyone would understand that since it was all USB 3.1, everything was compatible, right?

That single move made the entire 3.x naming system confusing. We now have USB 3.2 Gen1, Gen2, and even the doubled-interface Gen2x2, but what about ports and controllers that were labeled USB 3.0 and 3.1? Yep, those are now USB 3.2 Gen-whatever, for the most part. The portion after the decimal point became pointless and confusing. Perhaps that's why the upcoming USB4 standard (no space on purpose) has no decimals.

-- Thomas Soderstrom

Overpowered Gaming Desktop (2019)

The idea of Walmart making a gaming desktop for the masses isn’t inherently bad. That’s one way to get more people into PC gaming, after all. But the execution was all but legendary (in a bad way) among enthusiasts, giving the Overpowered brand name a bad rap very quickly.

We didn't expect a Walmart-brand PC to use high-end parts, but cheaping out on the power supply was really discomforting . The cable management was poor, the dust filters were inadequate, and god was it ugly. Some people found parts glued down, and that was enough for anyone considering it to look elsewhere.

-- Andrew E. Freedman

Samsung Galaxy Note 7 (2016)

When the Note 7 first launched in August of 2016, it received rave reviews, thanks to its beautiful curved display, handy S Pen and long battery life. There was just one problem with Samsung’s flagship: It had a tendency to randomly catch fire. After the company issued replacements for some phones, the replacements ignited too. All of these problems were eventually traced to faulty batteries.

Ultimately, Samsung had to recall every Note 7 and give consumers a special fireproof box to send the phone back in. And, for years, every time we boarded a plane, flight attendants announced that Galaxy Note 7s were banned. Many companies would go out of business after such a debacle that reportedly cost $5 billion. But just a few months later, the world’s largest phone vendor was back on track with huge profits.

-- Avram Piltch

Ouya (2013)

Among the most spectacular Kickstarter flameouts of the decade, this Android-based console is one of the few that actually shipped, but was an awesome failure in the real world. It had its own store that even played home to Towerfall, an exclusive that gained critical praise. But a poor controller and some bugs weren’t the worst part. There just weren’t a lot of games for it and Android never truly matured as a console gaming platform.

Ouya the company had some value, and Razer bought the content library after the console was discontinued in January 2015. That led to Razer’s Forge TV, which didn’t last long. Razer shut down the service in 2019, and now if you have an Ouya, it’s basically a paperweight.

-- Andrew E. Freedman

Steam Machines (2015)

There have been several attempts to get PCs into the living room, but Valve’s efforts behind Steam Machines never got off the ground. They were produced by partners like Alienware, Maingear, Zotac and other PC companies. The Linux-powered SteamOS didn’t take off, and some vendors switched to offering them with Windows. Seven months after their release, less than 500,000 units were sold, showing there wasn’t a ton of interest for these PCs -- at least in part because many AAA games didn't run on Linux.

Steam’s controller lasted a bit longer. The odd input device with two trackpads, an analog stick and rear buttons stuck around quietly until this year, when Valve put them on a $5 fire sale.

-- Andrew E. Freedman

Magic Leap (2018)

Oh Magic Leap. It never proved itself to be a magical tech and certainly didn’t leap into many consumers’ hands. The mixed-reality headset startup was founded in 2014 and eventually got a lot of attention from big-name investors, seeing $2.4 billion in funding and seeing a valuation of $6 billion.

But in 2018 when the company finally released the first product with its mixed-reality tech, the Magic Leap 1 Creator Edition, it sported a jaw-dropping $2,295 price tag and wasn’t even available in every state in the US at first. Granted, the headset is basically a spatial computer, as the company calls it, but it’s still way more expensive than any consumer VR headset and most computers people use in their homes daily.

The Magic Leap 1 is predominantly being ushered toward businesses and developers, and we still don’t have a timeline for a potential version that’s more consumer-friendly -- aka affordable at all. We’re still waiting for the magic, but we’re going to take a leap of our own and quit holding our breaths.

--Scharon Harding

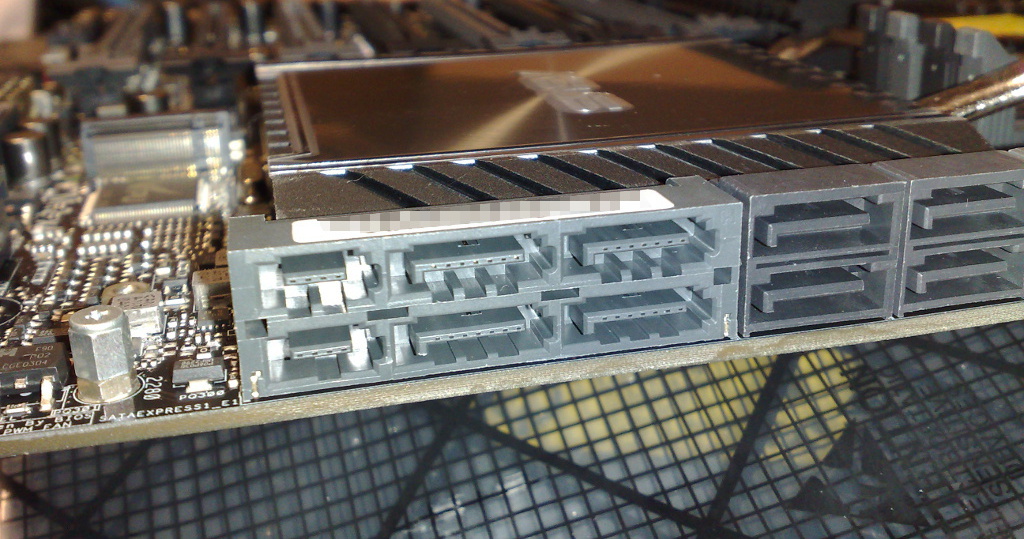

SATA Express (2014)

It’s hard to find any love for an interface that sucked up motherboard space for years, despite being dead on arrival. Initially created in 2013 (although boards didn't start showing up until a year later), SATA Express was an attempt to get past the looming limitations of SATA by pairing it with the bandwidth of two PCIe lanes. The problem? Beyond prototypes, no company ever launched any SATA Express drives for the consumer market, despite the ports getting placed on dozens of motherboard models. Heck, the chunky, clunky U.2 port got decidedly more uptake than SATA Express and it barely went anywhere in the consumer space, either.

Thankfully, we’ve moved past the bad idea that was SATA Express with the help of NVMe and M.2 drives, including new PCIe 4 models that push the bandwidth and speeds even further. You might still have a board with SATA Express connectors in your system now. The best part about these supposedly next-generation ports? They still work with regular-old SATA drives. So you can at least plug your hard drives or SATA SSDs into them to get some use out of the ports.

--Matt Safford

Apple Butterfly Keyboard (2015)

The keyboard that launched a thousand think-pieces and a repair program, the Butterfly keyboard was Apple’s biggest misstep in the last decade. The keyboard debuted with the 2015 MacBook, which also had a single USB-C port, and then spread to the MacBook Pro line and, ultimately, a refreshed MacBook Air. Nevermind the fact that they were polarizing with their low travel (I didn’t mind that part so much), these keyboards saw individual keys stop working, double-typing or other issues thought to be due to debris or the slim switches.

There were three generations of the keyboard, with fixes meant to make keys quieter or more tactile, but never officially to fix reliability issues. The repair program ultimately affected every laptop with that keyboard and is still in effect. It covers those devices for four years after the sale of the laptop.

This year, Apple released the 16-inch MacBook Pro and went back to scissor switches. Here’s hoping the rest of the company's lineup gets those as soon as possible.

-- Andrew E. Freedman

Windows RT/Windows on ARM (2012/2017)

While the Surface line of hardware eventually became a solid success, it’s initial launch in 2012 was in many ways a huge flop, costing the company as much as $1.7 billion in losses by 2014. The magnitude of the failure can be attributed in part to high initial prices, combined with unsold stock and the subsequent cancellation of the Surface Mini. But the main reason the initial Surface tablet didn’t sell was its operating system. Windows RT was compiled for Arm instead of x86 (the device was powered by an Nvidia Tegra 3 SoC). So the vast majority of Windows software just wouldn’t run on the device. And Microsoft couldn’t convince enough developers to jump aboard the RT bandwagon fast enough to make the initial Surface a satisfyingly functional product at its initial launch price--which was $500 without the keyboard.

Over the next seven years, Microsoft turned its Surface lineup around thanks to devices that run regular Windows, and are powered by Intel (and now AMD) processors. But Microsoft isn’t done with the idea of devices that run Windows on Arm. With the help of Qualcomm, in late 2017 companies began showing off new devices running on Snapdragon hardware. These devices are designed to deliver great battery life and always-on connectivity, just like your smartphone. The other to primary differences between Windows RT and Windows on ARM? Microsoft isn’t sticking its neck out by being the only company building the hardware this time (though it does have the Surface Pro X), and Windows on ARM is designed to run standard x86 software--in emulation.

But despite the best efforts of Qualcomm and Microsoft, we’re still quite skeptical about the long-term success of devices that run Windows on Arm. For starters, most of the devices launched so far have been significantly more expensive than the $500 Surface tablet. Native apps are still far-too-scarce, and the performance of x86 software running in emulation is generally disappointingly sluggish.

The platform is still improving, with support for Arm64 now possible and newly announced SoCs aimed at lowering the cost of Windows on Arm devices. But despite the benefits of long battery life and always-available connectivity, we think the vast majority of consumers will stick to standard Windows 10 devices that can run x86 code natively. Many users who value connectivity and long battery life and who don’t need Windows software have already moved on to Apple and Android devices anyway.

--Matt Safford

Tom's Hardware is the leading destination for hardcore computer enthusiasts. We cover everything from processors to 3D printers, single-board computers, SSDs and high-end gaming rigs, empowering readers to make the most of the tech they love, keep up on the latest developments and buy the right gear. Our staff has more than 100 years of combined experience covering news, solving tech problems and reviewing components and systems.

-

g-unit1111 The Bulldozer was a fail, sure, but that gave way to what may be one of the worst CPUs of the modern era ever made, maybe one of the worst CPUs of all time - the FX 9590. That CPU is such a fail that its' failures have been well documented and become a joke among the serious tech enthusiast and hobbyist communities, and even us moderators as well.Reply -

fball922 Steam Machines may have been a failure, but I still use my Steam Link regularly and even bought a second when they had their inventory clearance sale. It has its quirks, but has been a nice way to game anywhere in the house without moving my desktop.Reply -

NoFaultius Maybe it didn't sell enough units to get a mention, but the Leap Motion Controller was an abject fail. The idea of being able to manipulate your computer like Tom Cruise in Minority Report was a cool idea, but the implementation with the Leap was not a good user experience.Reply -

Exploding PSU About the Note 7, you see, after the recall Samsung re-launched the phone again in few regions as the "Note Fan Edition" (Note FE). It's pretty much the same phone, but with smaller battery and cheaper price tag (by flagship standards). I decided to pick one up, and it's actually a dam good phone (when it's not exploding left and right, of course). I still use it (am typing this on it right now) and have no intention of replacing it anytime soon, even though it looks quite old in the sea of borderless phone these days. It was a great deal back then, honestly.Reply -

g-unit1111 Replyexploding_psu said:About the Note 7, you see, after the recall Samsung re-launched the phone again in few regions as the "Note Fan Edition" (Note FE). It's pretty much the same phone, but with smaller battery and cheaper price tag (by flagship standards). I decided to pick one up, and it's actually a dam good phone (when it's not exploding left and right, of course). I still use it (am typing this on it right now) and have no intention of replacing it anytime soon, even though it looks quite old in the sea of borderless phone these days. It was a great deal back then, honestly.

Huh, I forgot that Samsung did that. My current phone is a Galaxy S9+ and it has been great so far, I have no plans to replace it currently but might if something cool comes along. -

cryoburner Reply

The company is still around though (or apparently merged with another company), and I suspect we will likely see Leap-like technology natively integrated into VR and AR headsets before long. And that kind of usage scenario seems like a much better fit for the hardware than desktop computers. The original device does seem to have been of questionable usefulness though.NoFaultius said:Maybe it didn't sell enough units to get a mention, but the Leap Motion Controller was an abject fail. The idea of being able to manipulate your computer like Tom Cruise in Minority Report was a cool idea, but the implementation with the Leap was not a good user experience. -

philipemaciel I would add the whole Windows Phone/10 mobile farce and the risible Core i3-8121U. Maybe the whole Intel 10 nm fiasco.Reply -

g-unit1111 ReplyCarlos Enrique said:Hey, you forgot Google Glass. Those terrible, useless and expensive glasses.

Yeah I think the only person who ever looked cool wearing Google Glasses was Tony Stark.