FreeSync: AMD's Approach To Variable Refresh Rates

AMD's FreeSync technology is gaining momentum, but is the buzz warranted? We did our own research, worked with Acer and spoke with AMD to find out.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Adaptive-Sync

Foundations First

Thanks to Bill Lempesis, Executive Director of VESA, we were able to both review the full DisplayPort 1.3 specification and preview a draft of the upcoming Adaptive‐Sync update, which is expected to be incorporated as an optional specification to the former standard. In May 2014, a similar addition was made to the earlier DisplayPort 1.2a standard—the first time that Adaptive-Sync was officially referenced as an industry standard.

Overall, the biggest catch in Adaptive-Sync is that it's optional. No VESA member is required to implement or support Adaptive-Sync. The certification routine is separate from that of DisplayPort itself. As of now, Adaptive-Sync does not even have its own logo! Having a display or GPU that exposes a DisplayPort connection is, in and of itself, no guarantee that it will support Adaptive-Sync. Sadly, as with all optional standards, consumers are bound to be confused.

Adaptive-Sync works by leveraging an optional DisplayPort feature. By telling the "sink" (the display) to "ignore main stream attributes," it can effectively use variable Vblank periods, creating a variable refresh rate.

Adaptive-Sync and the FreeSync standard built on top of it requires the specification of a certain range in which a display can operate on a variable refresh basis (for example, 30 to 144Hz). The range is set by the capabilities of the LCD panel and scaler, not by the GPU. The GPU is required to honor such a range requirement. Note that this range may not be, and typically is not, the full range of the display itself. For example, a display that can operate at fixed refresh rates of both 24Hz and 144Hz may opt to expose a variable rate of 35 to 90Hz.

The Adaptive-Sync standard does not cover how the system should behave when frame rates drop outside the supported range (below 30 frames per second or above 144 in a 30 to 144Hz range), except for implicitly stating that the refresh rate should not go above or below that range. It is left up to the GPU/driver combination to determine that.

All in all, the Adaptive-Sync standard is an exceptionally "light" standard. After all, the whole addendum is a mere two pages long. Especially because it's optional, it's unlikely that it will be the quick revolution wanted by gamers hoping for a rapid standardization of variable refresh rates.

Where It Gets Tricky

Two of the most exciting features found in modern LCDs are pixel transition overdrive and, in some of the newer panels, backlight strobing.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Both technologies dramatically improve the response time of LCD displays and lowering image persistence, significantly reducing the "ghosting" effect that has long plagued older LCD displays. If you're lucky enough to be younger than I am and have never played a first-person shooter on a CRT display, you ought to try one of these new strobing displays. They get really close to that experience, less the headache. Plus they weigh some 50 lbs. less. Then again, in this editor's tongue-in-cheek opinion, you're not a hardcore gamer until you've carried your own CRT display to a LAN party.

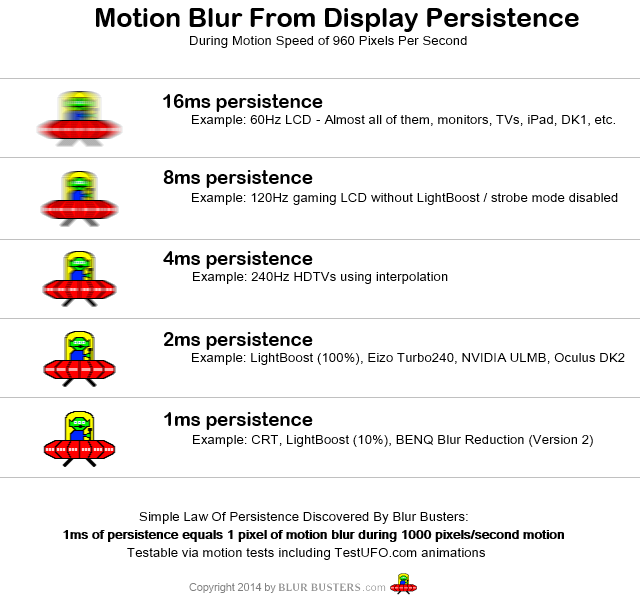

The image below is the best we've seen to characterize motion blur at different settings. Credit goes to the folks over at testufo.com.

Variable refresh rates pose an exceptional challenge to the two aforementioned technologies. The issue is that they've historically operated on the basis that the timing of frames was known. That is, in a fixed refresh ratio scenario, say 60Hz, every frame lasts 1/60 = 16.7 milliseconds. Therefore, voltages could be overdriven and backlights could be strobed while maintaining color consistency and a consistent global luminosity level.

Now, with FreeSync and G-Sync, the display does not know when the next frame will arrive or how long the current frame will be displayed. Consequently, it cannot easily overdrive pixel voltages without weird color outcomes. It cannot strobe on-demand, as display luminosity would vary in a maddening way as refresh rate varies dynamically. In order for these technologies to work, the display scaler would need to guess when the next frame will come and operate accordingly.

Display manufacturers only recently started to implement so-called variable refresh rate overdrive to help address this issue. We wrote about Nvidia's implementation in Nvidia's G-Sync Updates: Windowed Mode, Notebook Implementation, New Displays. Asus and its OEM partners added something similar to the upcoming MG279Q FreeSync display. Acer's XG270HU reportedly supports overdrive with FreeSync as well, but requires a firmware update and the version we tested didn't have it, unfortunately.

The operation principle of variable refresh rate overdrive is pretty simple. The display scaler guesses the next frame time based on previous frame times and varies the voltage overdrive setpoint accordingly (higher for shorter frame times, lower for longer frame times.) The worst that can happen, after all, is more ghosting than is ideal, and somewhat less accurate colors in scenes in motion. Either way, it works better than just disabling overdrive altogether.

The variable strobing challenge is more difficult to overcome from an engineering standpoint, and, at the time of this writing, no single OEM has even mentioned the possibility of variable pulse-width strobed displays. If low pixel persistence (that is, minimizing motion blur) is your highest concern, you will likely need to sacrifice G-Sync/FreeSync for months, if not years, to come.

Another challenge is windowed mode. On the desktop, there generally is no need for variable refresh rates. Where variable refresh rates come in handy is when you're playing 3D games or using 3D-accelerated applications. The former are usually played in full-screen mode, and display drivers are smart enough to recognize when a full-screen application takes over from Windows' Desktop Window Manager, and can thus enable the variable refresh rate.

But what if you want to play/operate in windowed mode? Windows' Desktop Window Manager is still handling desktop composition, and so you're stuck with fixed refresh rates. As matters stand, G-Sync enables variable refresh rate operation in windowed mode. AMD is looking into the capability, but hasn't estimated a target for its implementation.

My personal experience with G-Sync in windowed mode is a mixed bag at best. While some applications work better than others, Kerbal Space Program, for example, makes the entire desktop flicker to the point where I really wouldn't want G-Sync on at all. The flickering in other applications appears less extreme.

-

DbD2 Imo freesync has 2 advantages over gsync:Reply

1) price. No additional hardware required makes it relatively cheap. Gsync does cost substantially more.

2) ease of implementation. It is very easy for a monitor maker to do the basics and slap a freesync sticker on a monitor. Gsync is obviously harder to add.

However it also has 2 major disadvantages:

1) Quality. There is no required level of quality for freesync other then it can do some variable refresh. No min/max range, no anti-ghosting. No guarantees of behaviour outside of variable refresh range. It's very much buyer beware - most freesync displays have problems. This is very different to gsync which has a requirement for a high level of quality - you can buy any gsync display and know it will work well.

2) Market share. There are a lot less freesync enabled machines out there then gsync. Not only does nvidia have most of the market but most nvidia graphics cards support gsync. Only a few of the newest radeon cards support freesync, and sales of those cards have been weak. In addition the high end where you are most likely to get people spending extra on fancy monitors is dominated by nvidia, as is the whole gaming laptop market. Basically there are too few potential sales for freesync for it to really take off, unless nvidia or perhaps Intel decide to support it. -

InvalidError It sounds hilarious to me how some companies and representatives refuse to disclose certain details "for competitive reasons" when said details are either part of a standard that anyone interested in for whatever reason can get a copy of if they are willing to pay the ticket price, or can easily be determined by simply popping the cover on the physical product.Reply -

xenol I still think the concept of V-Sync must die because there's no real reason for it to exist any more. There are no displays that require precise timing that need V-Syncing to begin with. The only timing that should exist is the limit of the display itself to transition to another pixel.Reply

It sounds hilarious to me how some companies and representatives refuse to disclose certain details "for competitive reasons" when said details are either part of a standard that anyone interested in for whatever reason can get a copy of if they are willing to pay the ticket price, or can easily be determined by simply popping the cover on the physical product.

Especially if it's supposedly an "open" standard. -

nukemaster ReplyIt sounds hilarious to me how some companies and representatives refuse to disclose certain details "for competitive reasons" when said details are either part of a standard that anyone interested in for whatever reason can get a copy of if they are willing to pay the ticket price, or can easily be determined by simply popping the cover on the physical product.

It was kind of the highlight of the article.

(Ed.: Next time, I'll make a mental note to open up the display and look before sending it back. Unfortunately, the display had been shipped back at the time we received this answer)It is a shame that AMD is not pushing for some more standardization on these freesync enabled displays. A competition to ULMB would also be nice to see for games that already have steady frame rates. -

jkhoward Of course you think NVIDIA solution will win. You always do. This forum is becoming more and more bias.Reply -

InvalidError Reply

As stated in the article, modern LCDs still require some timing guarantees to drive pixels since the panel parameters to switch pixels from one brightness to another change depending on the time between refreshes. If you refresh the display at completely random intervals, you get random color errors due to fade, over-drive, under-drive, etc.16718305 said:I still think the concept of V-Sync must die because there's no real reason for it to exist any more.

While LCDs may not technically require vsync in the traditional CRT sense where it was directly related to an internal electromagnetic process, they still have operational limits on how quickly, slowly or regularly they need to be refreshed to produce predictable results.

It would have been more technically correct to call those limits min/max frame times instead of variable refresh rates but at the end of the day, the relationship between the two is simply f=1/t, which makes them effectively interchangeable. Explaining things in terms of refresh rates is simply more intuitive for gamers since it is almost directly comparable to frames per second. -

Freesync will clearly win, as a $200 price difference isn't trivial for most of us.Reply

Even if my card was nVidia, I'd get a freesync monitor. I'd rather have the money and not have the variable refresh rate technology. -

dwatterworth A suggestion for the high end frame rate issue with FreeSync, turn on FRTC and set it's maximum rate to the top end of the monitors sync range.Reply -

TechyInAZ Very interesting read. I never knew that variable refresh rates had effects on light strobing.Reply

I wonder how adaptive sync and G sync will work when the new OLED monitors start hitting the market?