Larrabee: Intel's New GPU

An Expected Comeback?

Intel’s re-entry in the market has generated a lot of excitement and new expectations. Intel is one of the few companies with both the financial wherewithal to get into the game and the requisite technology war chest to develop cutting-edge discrete GPUs. Intel is, thus, only competitor that can realistically shake up the established pecking order in this market. Nonetheless we should avoid any tendency to get carried away.

A decade ago, many people were thinking along the same lines about Intel’s arrival on the scene, and hopes were high. At that time, the market was divided into two categories: start-ups that offered first-rate 3D performance (3Dfx, Nvidia, and PowerVR) and heavy hitters who seemed to think that 3D acceleration was just a gadget (Matrox, S3, and ATI before AMD purchased it).

A lot of people hoped that Intel’s arrival would improve the health of the market by providing the assurance of a well-known name and unheard-of performance. Admittedly, at that time, Intel had a trump card up its sleeve: it had just bought out Real3D, which was famous for having worked on the Sega Model 2 and Model 3 arcade cards and was at the top of the heap at that time. Yet, despite its qualities, the i740 didn’t really live up to all the expectations that were riding on it, and cards like the Voodoo² and TNT quickly eclipsed its performance. Rather than continue to fight it out on this market, Intel decided to use the technology in its chipsets to be able to offer an integrated platform, which was a strategy that turned out to work well.

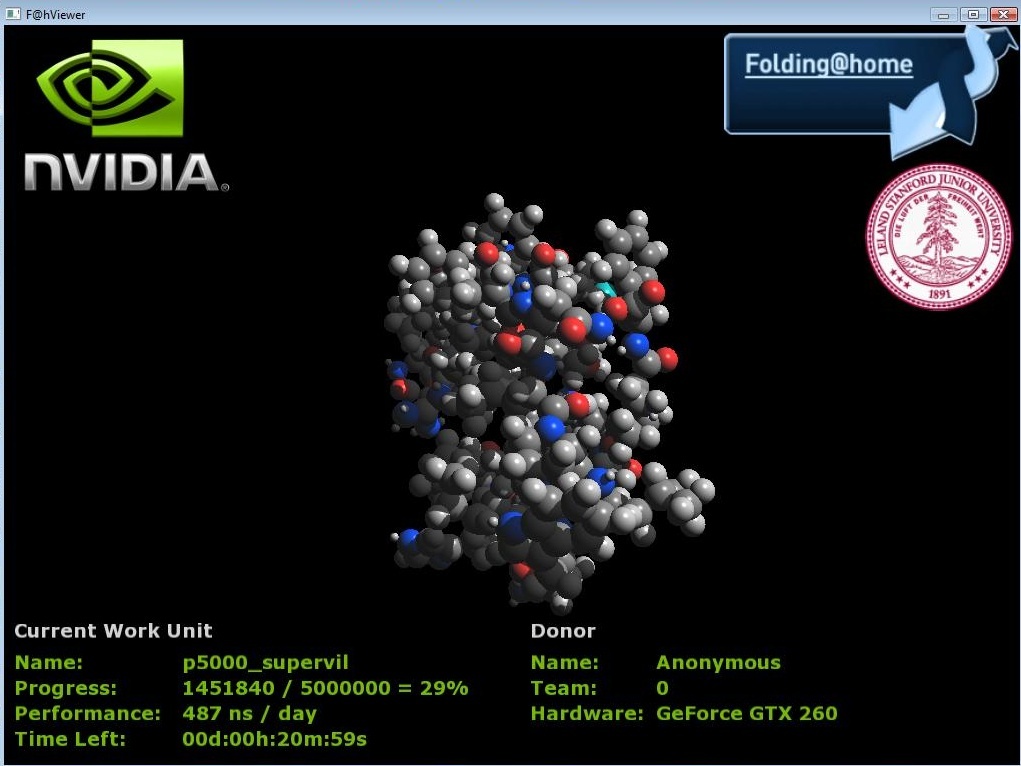

Things might have stayed the way they were, if certain researchers, given the trend for increasing the programmability of GPUs, hadn’t had the slightly offbeat idea of using it as a massively parallel general-purpose calculator.

While no one took the idea very seriously initially, it quickly garnered a lot of support--to the point where Nvidia and AMD, smelling an opportunity to conquer a new market, began issuing a lot of communication about it when launching their new GPUs. That was more than Intel could take. It wasn’t about to let GPUs start horning in on its bread and butter. The GPU, by taking over the most compute-intensive tasks, would make its high-end processors completely superfluous. The arrival of the GPU had already limited the effect of high-end CPUs in the gaming world, and it was essential for Intel to avoid having the same thing happen this time (and with broader consequences).

So it decided to react and offer an alternative--and as is often the case with Intel, that alternative was bound to be based on the old tried-and-true x86 architecture.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

-

thepinkpanther very interesting, i know nvidia cant settle for being the second best. As always its good for the consumer.Reply -

IzzyCraft Yes interesting, but intel already makes like 50% of every gpu i rather not see them take more market share and push nvidia and amd out although i doubt it unless they can make a real performer, which i have no doubt on paper they can but with drivers etc i doubt it.Reply -

Alien_959 Very interesting, finally some more information about Intel upcoming "GPU".Reply

But as I sad before here if the drivers aren't good, even the best hardware design is for nothing. I hope Intel invests more on to the software side of things and will be nice to have a third player. -

crisisavatar cool ill wait for windows 7 for my next build and hope to see some directx 11 and openGL3 support by then.Reply -

Stardude82 Maybe there is more than a little commonality with the Atom CPUs: in-order execution, hyper threading, low power/small foot print.Reply

Does the duo-core NV330 have the same sort of ring architecture? -

"Simultaneous Multithreading (SMT). This technology has just made a comeback in Intel architectures with the Core i7, and is built into the Larrabee processors."Reply

just thought i'd point out that with the current amd vs intel fight..if intel takes away the x86 licence amd will take its multithreading and ht tech back leaving intel without a cpu and a useless gpu -

liemfukliang Driver. If Intel made driver as bad as Intel Extreme than event if Intel can make faster and cheaper GPU it will be useless.Reply -

phantom93 Damn, hoped there would be some pictures :(. Looks interesting, I didn't read the full article but I hope it is cheaper so some of my friends with reg desktps can join in some Orginal Hardcore PC Gaming XD.Reply