Intel Core i7-3770K Review: A Small Step Up For Ivy Bridge

The Ivy Bridge Core: I Think I Know You

Intel purposely carries over a lot of the technology it introduced with Sandy Bridge, allowing the company to focus more intently on a smoother transition from 32 to 22 nm manufacturing. Thus, the capabilities of an Ivy Bridge-based IA core are very much similar to the prior generation.

Each core still hosts 32 KB of L1 data and L1 instruction cache, along with a 256 KB L2 cache. Moreover, quad-core models like the Core i7-3770K share up to 8 MB of last-level cache. Latencies appear very similar, indicating comparable cache bandwidth as Sandy Bridge.

Intel claims it made subtle adjustments to the IA cores, however, that improve performance in certain situations. Company representatives didn’t go into much detail about core architecture improvements at last year’s IDF, mentioning only that there are about half a dozen features in the core and another six or so more in the memory controller/cache that accelerate IA workloads. Fortunately, it’s easy enough for us to run a handful of single-threaded tests with Turbo Boost disabled to see how Core i7-3770K compares to Core i7-2700K, both operating at 3.5 GHz.

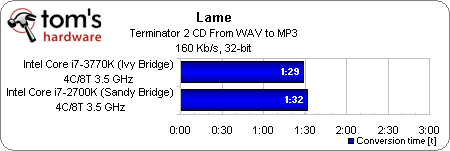

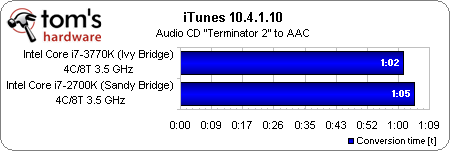

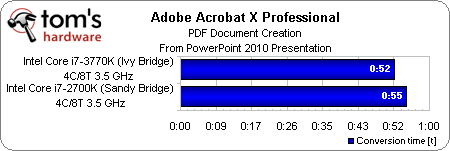

Ivy Bridge takes about three seconds off of our Lame, iTunes, and PDF creation metrics. That’s decidedly less impressive than what Sandy Bridge did compared to Nehalem—but again, it’s a result we expected.

The bottom line for enthusiasts is that Ivy Bridge’s IPC-oriented improvements alone are not compelling enough to warrant an upgrade from Sandy Bridge chips running at similar frequencies.

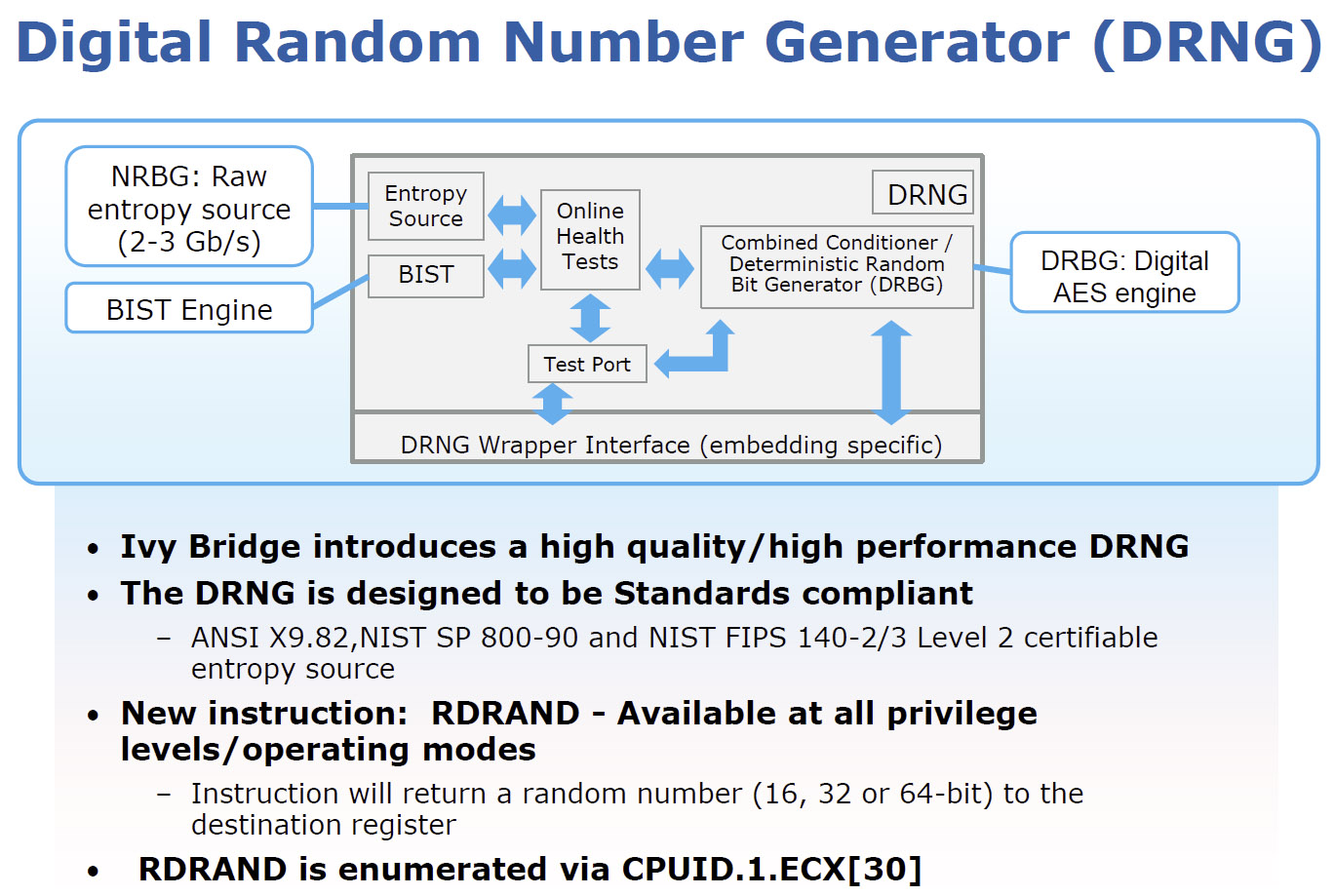

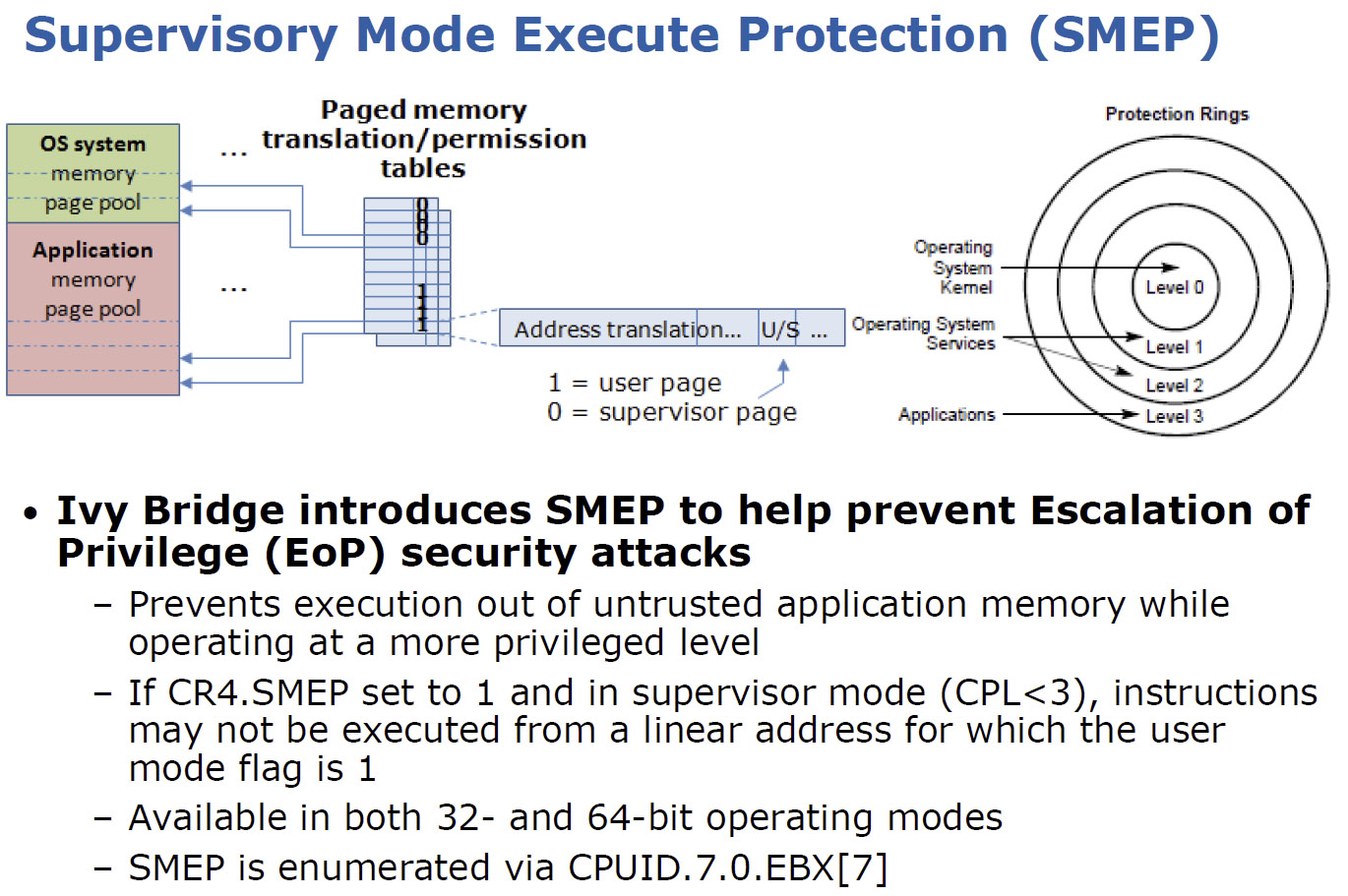

Intel does incorporate a pair of security-oriented features that software developers will be able to exploit moving forward: a Digital Random Number Generator instruction and Supervisor Mode Execution Protection.

Designed to be standards-compliant, the DRNG’s purpose is to provide a high-quality and high-performance source of entropy—the measure of a cryptographic key’s unpredictability. As a result, an application can exploit the DRNG, and get reliably good random numbers at up to 2-3 Gb/s. Intel makes the instruction available to operating system- and user-level code at all privilege levels.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

The other new feature, abbreviated SMEP, attempts to thwart escalation of privilege attacks that seek access to resources normally protected from a less privileged ring. Simply, it prevents the execution of supervisor mode code in user-mode memory pages.

Current page: The Ivy Bridge Core: I Think I Know You

Prev Page Ivy Bridge: Was It Worth The Wait? Next Page HD Graphics 4000: The Plus In Intel’s Tick+-

tecmo34 Nice Review Chris...Reply

Looking forward to the further information coming out this week on Ivy Bridge, as I was initially planning on buying Ivy Bridge, but now I might turn to Sandy Bridge-E -

jaquith Great and long waited review - Thanks Chris!Reply

Temps as expected are high on the IB, but better than early ES which is very good.

Those with their SB or SB-E (K/X) should be feeling good about now ;) -

xtremexx saw this just pop up on google, posted 1 min ago, anyway im probably going to update i have a core i3 2100 so this is pretty good.Reply -

ojas it's heeearrree!!!!! lol i though intel wan't launching it, been scouring the web for an hour for some mention.Reply

Now, time to read the review. :D -

zanny It gets higher temps at lower frequencies? What the hell did Intel break?Reply

I really wish they would introduce a gaming platform between their stupidly overpriced x79esque server platform and the integrated graphics chips they are pushing mainstream. 50% more transistors should be 30% or so more performance or a much smaller chip, but gamers get nothing out of Ivy Bridge. -

JAYDEEJOHN It makes sense Intel is making this its quickest ramp ever, as they see ARM on the horizon in today's changing market.Reply

They're using their process to get to places they'll need to get to in the future -

verbalizer OK after reading most of the review and definitely studying the charts;Reply

I have a few things on my mind.

1.) AMD - C'mon and get it together, you need to do better...2.) imagine if Intel made an i7-2660K or something like the i5-2550K they have now.

3.) SB-E is not for gaming (too highly priced...) compared to i7 or i5 Sandy Bridge

4.) Ivy Bridge runs hot.......

5.) IB average 3.7% faster than i7 SB and only 16% over i5 SB = not worth it

6.) AMD - C'mon and get it together, you need to do better...

(moderator edit..) -

Pezcore27 Good review.Reply

To me it shows 2 main things. 1) that Ivy didn't improve on Sandy Bridge as much as Intel was hoping it would, and 2) just how far behind AMD actually is... -

tmk221 It's a shame that this chip is marginally faster than 2700k. I guess it's all AMD fault. there is simply no pressure on Intel. Otherwise they would already moved to 8, 6, and 4 cores processors. Especially now when they have 4 cores under 77W.Reply

Yea yea I know most apps won't use 8 cores, but that's only because there was no 8 cores processors in past, not the other way around