9 Things You Didn’t Know About Overclocking Competitions

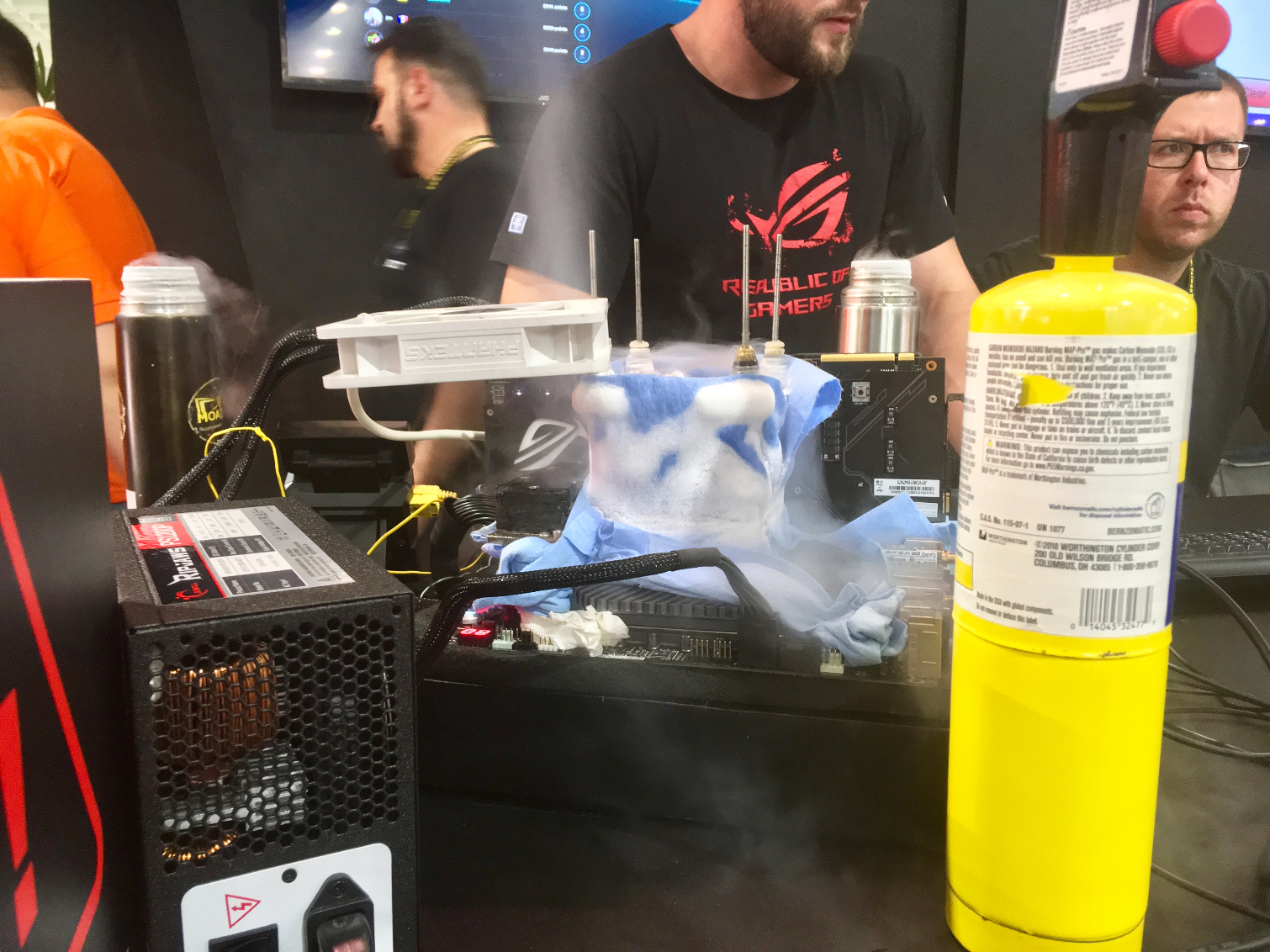

Overclockers already live in a fascinating world. It’s a foggy one, clouded by all the liquid nitrogen (LN2), populated by lots of components, some fried, others about to get pushed to the brink of their capabilities. But nothing is as intense as a live overclocking competition.

During last week’s Computex tech conference in Taipei, nine of the world’s best overclockers competed in G.Skill’s 6th Annual OC World Cup for a grand prize of $10,000 and a TEK-9 Icon 3.0 GPU LN2 pot from Kingpin Cooling. Contestants were challenged with four benchmarks with just 30 minutes to lock in a top score for each, before the top three finalists competed with five benchmarks, including one each selected by the competitors. Ultimately, a Romanian overclocker known as Alex@ro took the crown.

Tom’s Hardware met with a couple of the competition’s judges to get a behind-the-bench look at what goes into a world renowned overclocking tournament, besides masses of LN2. Here are nine things you may be surprised to hear.

1. Overclockers’ Own Money Is On the Line

Competitive overclockers are often sponsored by vendors. But for some competitions you supply your own components (“There’s no ROI for the company if they kill 10 boards, 10 CPUs and memory; that costs heaps of money,” Mesotten noted). Sometimes, including at G.Skill’s Computex competition in Taiwan, entrants pay for their own transportation too.

Remember that participant we mentioned earlier who blew two 9900Ks and a motherboard? He flew himself from Europe to Taipei. Imagine the hole he’s in if he doesn’t place. The fifth place prize, $1,000, wouldn’t even cover all the damage. Perhaps that’s why he was seen throwing things around out of frustration.

2. Weather Matters

In addition to fighting the clock, clock speeds, nerves and the need to win, overclocking competitors may find their usual tactics disrupted by weather conditions. At Computex, it was Taipei’s humid air overclockers had to contend with.

Someone from a humid area may have an advantage, but those who didn’t consider this, like the many newcomers at the G.Skill World Cup, faced an unfortunate learning curve.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

“Humidity is the measurement of water in the air basically. So if you have a lot of water in the air, the LN2 gets so cold it’ll start sweating. It starts condensating. The more humidity you have, the more condensation occurs,” Stepongzi explained.

The more crowded the show floor gets, the hotter it is. And if it rains while you’re competing, like it did heavily during Computex, humidity is even worse. For example, that week, Mesotten saw ice melting, even at -196 degrees Celsius.

In case you’re wondering how to deal with that humidity, Stepongzi says they usually put Vaseline or liquid or electrical tape on the motherboard to help create a barrier preventing water from falling onto the motherboard and components.

3. Competitors Make a Lot of Dumb Mistakes

With a bucket load of cash at stake, overclockers make surprising mistakes during tournaments. We call these dumb mistakes not because we think we could do better, but because they’re basic mistakes that these pros would usually know to avoid.

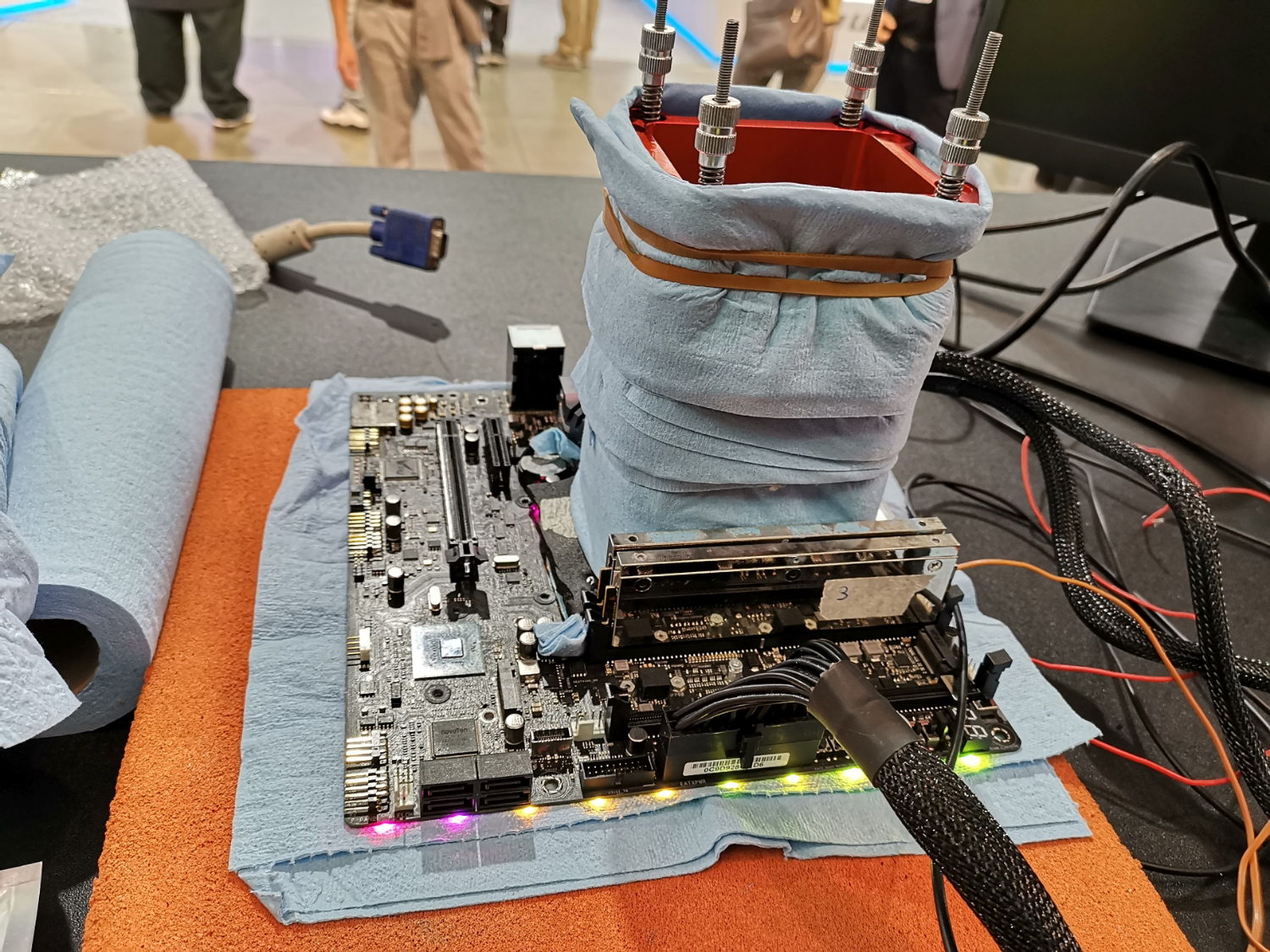

We won’t name names, but one participant at G.Skill’s World Cup this year ended up killing not one, but two different Intel Core i9-9900K CPUs due to poor insulation.

“You have your processor, and you put the copper pot on top and we usually put towels around for the moisture. He had the towel in between, so there was no contact so he just burned it,” Mesotten recalled. He noted that this is usually the first thing you check: you enter the BIOS and watch your temperature meter. If it’s around 10 degrees Celsius, that’s okay. Mesotten suspects that person would’ve seen that the CPU was 40 degrees off if he checked.

“He immediately cranked up all the volts, then cooled down, but the CPU didn’t get cold enough. So it just burned inside the board,” Mesotten explained. By the way, at the time of this writing, a Core i9-9900K CPU is selling for about $500.

Mesotten recommends overclockers always enter a placeholder score, just in case things go wrong down the line. Mesotten told this to the aforementioned competitor who had posted just one score two days into the competition, but they decided to wait until they had a better score.

“An hour later, his CPU dies, his motherboard is dead and today his second CPU is dead. He fried everything,” Mesotten said.

Another entrant was shouting about his CPU being junk because it wasn’t overclocking anymore. When time was up, the judges were sorry to inform him that it was because he was constantly changing the wrong voltage; the one he needed was two settings above.

4. They’re All Nervous

Behind the high stage and clouds of LN2 are a bunch of nervous nellies, judges at G.Skill’s latest bout told us.

In fact, tensions were so high, that G.Skill had to put a ban on press and media conducting interviews or shooting photo / video of the overclockers from behind the stage.

Albrecht Mesotten, aka leeghoofd, a judge at G.Skill’s competition this year and professional overclocker since 2009, noted one competitor who hadn’t slept in three days and who is self-admittedly “always nervous.” Mesotten pointed out that at home, overclockers can re-do things when they see something, like the CPU clock speed, is off. But in a competition, you’re limited by time constraints.

“Most of the new guys that are there, they’re kind of freaking out because it’s so much at once. They get nervous, and they’re not used to the type of competition arrangement because we try to make it brutal,” Joe Stepongzi, aka steponz, another judge and competitive overclocker since 2009, told Tom’s Hardware. “It’s to win a lot of money, so we’re not just going to give you money. You need to be skilled; you got to work for it."

He added that while preparation helps, and you can tell those who have prepared from those who haven’t, sometimes just being nervous can hurt competitors. Good-bye comfort zone, and hello to what Stepongzi describes as “probably one of the worst places to do this.”

“At home you have everything there; you have everything u need. When I’m at home, I have a setup that just sits there. Pop a switch on, and everything’s connected. When you go to a competition, you always have to think, ‘did I bring this? do I have that?’ You end up losing track of your normal stuff,” he said. “Sometimes you get so into the competition, you’re like ‘I forgot this,’ and just because you forgot one thing, it gets you all stressed out and ruins your whole flow.”

5. Preparation Is Everything, but Not Everyone Prepares

Practice, practice, practice, right? It seems sometimes overclockers forget that adage. Despite getting “hints,” as Mesotten put it, beforehand around what version of Windows 10 would be used and the type of memory, the judge said he was surprised at how many competitors didn’t do any pre-testing before coming to Taipei. Judges also announced the benchmarks a month in advance.

For G.Skill’s four-day event, time was of the essence. But with some competitors failing to prepare before the show and lacking the comfort of having time to tweak at their leisure, we saw a lot of easily avoidable errors.

6. Today’s Motherboard Options Are Limited

Mesotten pointed out that judges’ jobs have gotten a little easier with there being fewer vendors making overclock-ready motherboards than in the past. At this particular event, only boards from Asus and MSI were used by the competitors. Gigabyte stopped selling overclocking motherboards around the debut of the X99 chipset in 2014.

“The issue is we want special features, like better VRMs, PWM,” Mesotten said. “We also want special things in the BIOS. Usually, Asus with their ROG series is on top of their game. Each time a new product launches they’re ready because they have the good R&D team and some in house overclockers as well.”

The good thing is that some of those boards come with special BIOSes for overclockers that motherboard vendors don’t generally share with the public, since they can break components.

7. Memory Vendors Are Hot for DDR4 World Records Right Now

The current world record for DDR4 memory was set with G.Skill’s Trident Z Royal memory at Computex last week. The name of the memory vendor associated with the DDR4 record-holder has been changing frequently of late. Just look at last month, when Micron snatched the throne from Adata, just a day after Adata got it.

DDR4 hit consumers in 2014, so by now every memory vendor has a version to push. One method for making sure consumers see their product is by having it tied to a world record.

“It’s more of a marketing-type thing. Everybody’s like, ‘we got to make sure our memory’s the best.’ This is a crazy time for it,” Stepongzi told us.

Mesotten agreed that since G.Skill is primarily focused on memory rather than other PC components (it also sells SSDs, PSUs and memory coolers), it’s important to them that they be ranked number one.

8. Judges Have Their Work Cut Out For Them

Judges like Stepongzi and Mesotten are put to work at overclocking competitions as well, with their work starting in January, about five months before the actual competition. Responsibilities include tasks like installing the operating systems on all the systems.

For G.Skill’s bout, the judges also had to bin all the RAM sticks to be used. It took about three days for the judges to go through hundreds of modules and make sure they all perform relatively equal.

The great equalizers, the judges also selected the benchmarks, based on their years of expertise, and went through them to make sure they weren’t being buggy.

“We try and pick something that’s legit; that way we keep everything level,” Stepongzi said. “We really spend a lot of time ... talking about it and figuring out how we want to do things.”

9. Not All Overclocking Competitions Are Created Equal

The judges told us that the reason they’re so passionate about making sure there’s a level playing field is because they’ve experienced contests where that was not the case. Stepongzi thinks other overclocking tournaments aren’t as good as the G.Skill World Cup, due to poor execution.

Mesotten told us about a six-hour-long overclocking competition by another vendor where, when judges were about to name a winner, the organizer stopped them, saying that they decided to add 30 minutes to the contest, because one participant had a slow start due to SSD issues. The would-be winner, however, was already shutting down his system by then. At the end of the day, he ended up ranking fifth.

“If you change a rule, you have to ask the competitors so everyone knows. Apparently, somebody with a paper walked around [while contestants were] pouring and watching their screen … and half of them didn’t see it,” Mesotten recalled. “A thing like this should not happen at this high level.”

Hungry for more overclocking secrets? Be sure to check out our article on How to Become a Competitive Overclocker, the official world rankings on HWBot (tip: you can learn a lot from images includes with submissions) and watch some highlights from G.Skill’s 6th Annual OC World Cup at Computex via Stepongzi’s YouTube channel.

Scharon Harding has over a decade of experience reporting on technology with a special affinity for gaming peripherals (especially monitors), laptops, and virtual reality. Previously, she covered business technology, including hardware, software, cyber security, cloud, and other IT happenings, at Channelnomics, with bylines at CRN UK.