60/64 GB SSD Shootout: Crucial, Samsung, And SandForce

Storage Bench v1.0, In More Detail

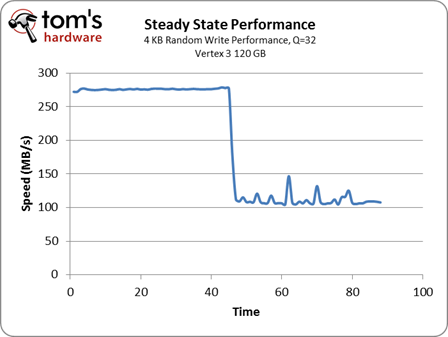

SSD manufacturers prefer that we benchmark drives the way they behave fresh out of the box because solid-state drives slow down once you start using them. If you give an SSD enough time, though, it will reach a steady-state performance level. At that point, its benchmark results reflect more consistent long-term use. In general, reads are a little faster, writes are slower, and erase cycles happen as slow as you'll ever see from the drive.

We want to move away from benchmarking SSDs fresh out of the box whenever possible because you only really get that performance for a limited time. After that, you end up with steady-state performance until you perform a secure erase and start all over again. Now, we don't know about you, but we don't reformat our production workstations every week. So, while performance right out of the box is an interesting metric, it's not nearly as relevant in the grand scheme of things. Steady-state performance is what ultimately matters.

While this is a new move for us, IT professionals have long used this approach to evaluate SSDs. That's why the consortium of producers and consumers of storage products, Storage Networking Industry Association (SNIA), recommends benchmarking steady-state performance. It's really the only way to examine the true performance of an SSD in a way that represents what you'll actually see over time.

There are multiple ways to get there, but we're going to use Intel’s IPEAK (Intel Performance Evaluation and Analysis Kit). This is a trace-based benchmark, which means that we're using an I/O recording to measure relative performance. Our trace, which we're dubbing Storage Bench v1.0, comes from a two-week recording of my own personal machine, and it captures the level of I/O that you would see during the first two weeks of setting up a computer.

Installation includes:

- Games like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, Crysis 2, and Civilization V

- Microsoft Office 2010 Professional Plus

- Firefox

- VMware

- Adobe Photoshop CS5

- Various Canon and HP Printer Utilities

- LCD Calibration Tools: ColorEyes, i1Match

- General Utility Software: WinZip, Adobe Acrobat Reader, WinRAR, Skype

- Development Tools: Android SDK, iOS SDK, and Bloodshed

- Multimedia Software: iTunes, VLC

The I/O workload is somewhat moderate. I read the news, browse the Web for information, read several white papers, occasionally compile code, run gaming benchmarks, and calibrate monitors. On a daily basis, I edit photos, upload them to our corporate server, write articles in Word, and perform research across multiple Firefox windows.

The following are stats on the two-week trace of my personal workstation:

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

| Statistics | Storage Bench v1.0 |

|---|---|

| Read Operations | 7 408 938 |

| Write Operations | 3 061 162 |

| Data Read | 84.27 GB |

| Data Written | 142.19 GB |

| Max Queue Depth | 452 |

According to the stats, I'm writing more data than I'm reading over the course of two weeks. However, this needs to put into context. Remember that the trace includes the I/O activity of setting up the computer. A lot of this information is considered one-touch, since it isn't accessed repeatedly. If we exclude the first few hours of my trace, the amount of data written drops by over 50%. So on a day-to-day basis, my usage pattern evens out to include a fairly balanced mix of read and writes (~8-10 GB/day). That seems pretty typical for the average desktop user, though this number is expected to favor reads among the folks consuming streaming media on a larger and more frequent basis.

On a separate note, we specifically avoided creating a really big trace by installing multiple things over the course of a few hours, because that really doesn't capture real-world use. As Intel points out, traces of this nature are largely contrived because they don't take into account idle garbage collection, which has a tangible effect on performance (more on that later).

Current page: Storage Bench v1.0, In More Detail

Prev Page Crowning An Entry-Level SSD Performance King Next Page More Background On Our Benchmarks-

Wow. Absolutely wonderful article. I did second guess my decision on SSD for my next build for a few. But honestly I'm just using it as a boot drive.Reply

-

acku kixofmyg0tWow. Absolutely wonderful article. I did second guess my decision on SSD for my next build for a few. But honestly I'm just using it as a boot drive.Reply

Glad to hear that!

Cheers,

Andrew Ku

TomsHardware.com -

rossi004 Ok, so I have the whole SSD for boot, HDD for storage and less intensive programs, but I have a practicality question:Reply

Is there a way to have files and programs automatically downloaded, installed, and run from the HDD without doing it manually every time if I have the SSD as the base drive?

-

james_1978 rossi004Ok, so I have the whole SSD for boot, HDD for storage and less intensive programs, but I have a practicality question:Is there a way to have files and programs automatically downloaded, installed, and run from the HDD without doing it manually every time if I have the SSD as the base drive?Reply

You can move your personal folders to your HDD (my documents, my music, downloads, ...), so downloads will end up there automaticaly, but programs will go to your C drive (SSD) by default. -

james_1978 james_1978You can move your personal folders to your HDD (my documents, my music, downloads, ...), so downloads will end up there automaticaly, but programs will go to your C drive (SSD) by default.Ok, sorry, but actually you can move your program files by editing the registry:Reply

Moving only user files is far easier nevertheless, just using "move" in the folder properties... -

james_1978 james_1978Ok, sorry, but actually you can move your program files by editing the registry:Moving only user files is far easier nevertheless, just using "move" in the folder properties..."Add an url" didn't quite work for me :-)Reply

http://www.tomshardware.com/forum/6643-63-windows-boot-drive-user-files-program-files-normal -

Soul_keeper nice articleReply

Worth mentioning, plextor PX-M3S are micron based and use toggle nand

I don't think they make a 64GB version however