Part 2: 2D, Acceleration, And Windows: Aren't All Graphics Cards Equal?

Introduction: Why GDI Output For 2D Graphics Remains Relevant

First things first: if you haven't yet read 2D, Acceleration, And Windows: Aren't All Graphics Cards Equal?, please feel free to check that one out first, since it's the Part 1 to this Part 2 exploration into the history of 2D in Windows and current issues seen on high-end discrete graphics cards.

In this second part, we focus on the relevance of GDI, explain 2D graphics output more completely, and present to you our 2D benchmark (for the folks who haven't already discovered it on Tom's Hardware DE). In order to fully understand the results from that benchmark, we must first dig into some related theoretical fundamentals.

Why Do We Still Test GDI in the Era of Windows 7 and Direct2D?

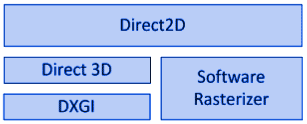

In the first part of this series, a number of readers speculated that, with the introduction of DirectX 10-capable graphics cards and Windows Vista, older GDI methods for 2D graphics output were rendered obsolete. The WPF (Windows Presentation Foundation), along with Direct2D, have been available to Microsoft developers for some time now. Nevertheless, there are plenty of good reasons why GDI (the Graphics Device Interface) remains unarguably meaningful and relevant, which means we must examine its behavior and performance, even for the brave new world of Windows 7. These reasons include:

- The GDI continues to support older graphics cards, while Direct2D requires cards that can support DirectX 10 or better.

- GDI is supported in every known version of Windows, whereas Direct2D is available only in Windows Vista and Windows 7.

- Every graphics application that runs under Windows XP (and older Windows versions) uses GDI

Lots of software developers resist converting their software from older to newer APIs. Even today, many developers continue to turn to the same well-understood programming libraries, even if newer technologies are available. Converting from one library to another also means rewriting and retesting all affected code modules. Because performance improvements that result from converting from an older library to a newer one may be barely perceptible, software developers also balk at making such changes on purely economic grounds (too much time and effort for too small of a result). If you take the implementation of Direct2D in various components of Mozilla Firefox as an illustrative example, you get a sense of the industry’s leisurely pace in carrying out this conversion process. In addition, it would be a form of business suicide for many of these firms to lock the entire community of XP users out of their latest releases. All of this adds up to a single compelling observation: the GDI is likely to stick around until Windows XP no longer represents any significant component of the end-user community.

Then there are technical reasons to explain the persistence of GDI. Key GDI code modules (those that are included and invoked most often in Windows applications) aren't completely portable. Direct2D also consumes significant processing power and system resources, but can do nothing that Direct3D cannot also deliver. And those who elect to skip using Direct3D have usually considered this decision quite carefully. In addition, the GDI works independently of the output devices, such as monitors or printers, that may be in use. Thus, the same routine in a program can render graphics on a monitor, and output to a printer, thereby reducing the code (and its subsequent maintenance and error risk) by as much as one-half. Many of the most affordable printers are GDI devices nowadays, and this situation is unlikely to change any time soon, even in Windows 7, where plenty of drivers for GDI-only printers remain widely available.

The Whole Is More Than the Sum of All Parts

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

We ourselves view the conversion to WPF and Direct2D as a move that’s being pushed forcibly by Microsoft, and as an irreversible technical step forward. But those who get all hot and bothered by new technology should think back to previous introductions, which we'll recap in this piece. Windows XP included, there is more than enough legacy technology hanging around that you can really only face the future if you’re willing to ignore the past. But alas, this disregards the realities in which most users operate, such as the well-known phobia for Windows XP shown by 780G and 785G on-board graphics chips.

We want to revisit our benchmarks from Part 1 here, but this time we’ll use our own custom-built software (readers can also download this tool from our site, and run it on their own PCs). We'll observe that even the most expensive graphics cards fall flat on some of these tests, if they’re affected by drivers that haven't been optimized for what many folks consider an older technology.

Current page: Introduction: Why GDI Output For 2D Graphics Remains Relevant

Next Page The 2D GDI For Windows XP Through Windows 7, In DetailTom's Hardware is the leading destination for hardcore computer enthusiasts. We cover everything from processors to 3D printers, single-board computers, SSDs and high-end gaming rigs, empowering readers to make the most of the tech they love, keep up on the latest developments and buy the right gear. Our staff has more than 100 years of combined experience covering news, solving tech problems and reviewing components and systems.

-

mdm08 I have a 5850 with 10.1 drivers and it seems Photoshop CS4 doesn't recognize it as a graphics card that can improve performance so all those cool new features like animated zoom, kinetic panning, and such seem to be disabled. Also, it when you have a very complex group of objects and you try to nudge it ( move it one pixel with arrow keys) the computer actually shows the spinning wheel and has to process this instead of being instantaneous like it was on my older 7600GT. Is this an issue related with what this article is saying about apps written for GDI or is this a different issue i'm experiencing?Reply -

jrharbort Scores on 9600M GT and T9600 Core 2 Duo with Windows XP and latest graphics drivers. Only 11 active background processes no including benchmark, and themes disabled.Reply

BENCHMARK: DIRECT DRAWING TO VISIBLE DEVICE

Text: 8556 chars/sec

Line: 47513 lines/sec

Polygon: 7757 polygons/sec

Rectangle: 6564 rects/sec

Arc/Ellipse: 3874 ellipses/sec

Blitting: 13974 operations/sec

Stretching: 266 operations/sec

Splines/Bézier: 10510 splines/sec

Score: 984 -

It would be great if you can run the test on some "pro" cards (quadroFX, quadroNVS, firePro & fireMV). Just to see if the "pro" drivers change standard UI rendering or the optimizations are only for the professional DCC software.Reply

-

liquidsnake718 mdm08I have a 5850 with 10.1 drivers and it seems Photoshop CS4 doesn't recognize it as a graphics card that can improve performance so all those cool new features like animated zoom, kinetic panning, and such seem to be disabled. Also, it when you have a very complex group of objects and you try to nudge it ( move it one pixel with arrow keys) the computer actually shows the spinning wheel and has to process this instead of being instantaneous like it was on my older 7600GT. Is this an issue related with what this article is saying about apps written for GDI or is this a different issue i'm experiencing?Oh great, more news on a 5xxx series not being able to handle simple apps like CS4.... I have yet to use CS4 on my desktop with my 5850..... I hope Ati comes out with more patches if this is a problem.Reply -

taltamir windows XP is dead... get on the windows 7 64bit bandwagon already you Luddites! (not referring to the authors of the article, they raise good points; I am referring to those customers who insist that XP is some sort of holy grail of windows bliss never seen before or after)Reply -

Scores on P4 2.8 HT Northwood W ati 2600 pro drivers 10.1 aero Win 7 :Reply

BENCHMARK: DIRECT DRAWING TO VISIBLE DEVICE

Text: 8106 chars/sec

Line: 6528 lines/sec

Polygon: 249 polygons/sec

Rectangle: 1484 rects/sec

Arc/Ellipse: 6127 ellipses/sec

Blitting: 379 operations/sec

Stretching: 80 operations/sec

Splines/Bézier: 5263 splines/sec

Score: 362 -

Scores on P4 2.8 HT Northwood W ati 2600 pro drivers 10.1 aero Win 7 :Reply

BENCHMARK: DIB-BUFFER AND BLIT

Text: 12633 chars/sec

Line: 21067 lines/sec

Polygon: 4087 polygons/sec

Rectangle: 535 rects/sec

Arc/Ellipse: 5604 ellipses/sec

Blitting: 1443 operations/sec

Stretching: 213 operations/sec

Splines/Bézier: 12213 splines/sec

Score: 607 -

giovanni86 BENCHMARK: DIRECT DRAWING TO VISIBLE DEVICEReply

Text: 54466 chars/sec

Line: 73135 lines/sec

Polygon: 23943 polygons/sec

Rectangle: 3927 rects/sec

Arc/Ellipse: 26911 ellipses/sec

Blitting: 9827 operations/sec

Stretching: 464 operations/sec

Splines/Bézier: 41911 splines/sec

Score: 2600 -

helle040 Rdaeon 4670, amd 7750be, winxp, drivers 10.1, resolutie 1280x1024, 32bitReply

Text: 45746

line: 40508

Splines/beziers: 20466

Poygon: 322

Rectangle: 1954

Arc/E.: 3494

Biting: 2406

Stretching: 211

Score: 1150 -

wxj I’ve always preferred GDI operations over those of the NOD. GDI have more basic operations set verses NOD’s more complex and sometimes unreliable operations.Reply